Paradigms of Movement Composition

Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt

Translated from the original Swedish by Suzanne Martin Cheadle

This essay was developed with support from ke∂ja Writing Movement (www.writingmovement.com)

Paradigms of Movement Composition

My background is that of a dancer. Since childhood I have also been a storyteller. This made it difficult for me to understand why there had to be such a sharp line between dance and theater, between magic and realism, between movement and text. Is that line about to be erased?

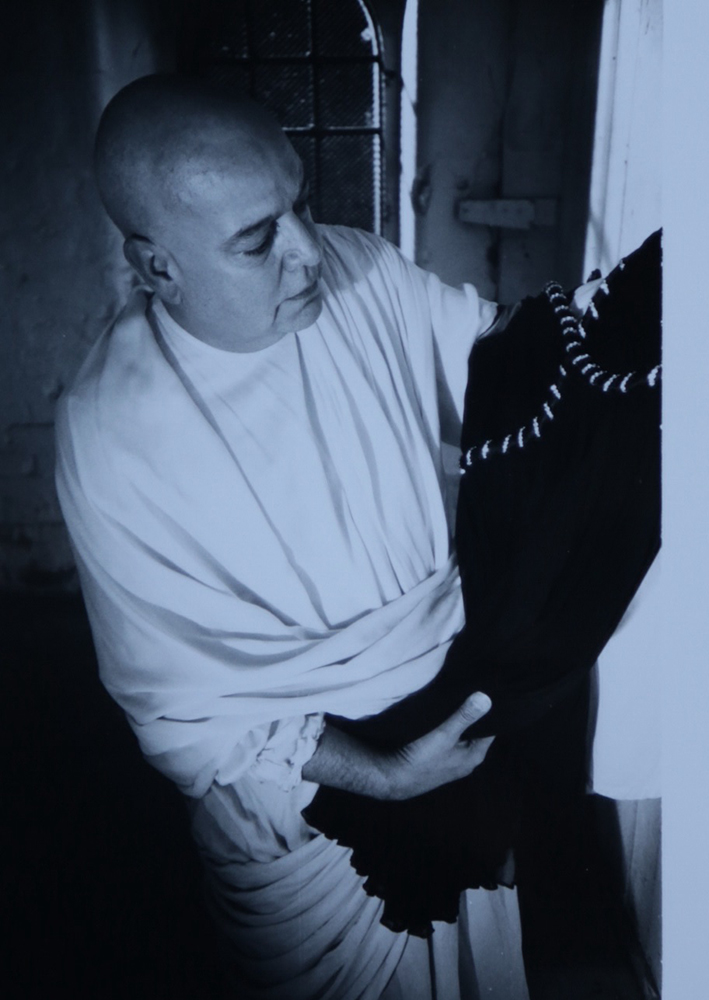

Photo of Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt in the performance 20xLamentation 2013 (by Laila Östlund). Courtesy of the artist.

In the beginning of the film era, actors were also dancers. The training of bodily posture and gesture was essential for the stars of silent cinema. In silent films, movements were there to prove the moving image. When talkies first appeared in the beginning of the 1930s, dance continued to enhance the dramatic or emotional events in a film. By the same time in India, the foundation had already been laid for the large film production industry that today employs many choreographers and dancers. A Bollywood film is not complete without the actors breaking out in dance. And, looking further eastward, what would a Kung Fu film be without an aesthetically choreographed fight? To me it seems that when European and American film gradually became more and more realistic and psychological, film-makers refrained from expressive movements, and instead employed a literary model. Dance became increasingly rare in Hollywood.

Dance film, therefore, while not exactly a new genre, has only recently become its own artistic genre, developing in new directions and enjoying a new autonomy. New dance film festivals are popping up all over the world—festivals where dance film is the rule and not the exception.[1] I have found freedom in these festivals where dance is celebrated as the fundamental component, and where we can ask questions about what dance is, or could be. However, when a dance film is shown, and becomes the distinctive ingredient within a feature film festival, it reaches and challenges new audience members. The narrative of dance films examines states of mind, situations, places, and meetings rather than telling a story. It does not have to be realistic or psychological. Dramatic situations that are built up only to be later resolved are absent from this realm. Dance film offers a change of the conventions of feature film. Who knows, Hollywood might get interested again.

My own very first experiment with dance and film: Gothenburg, October 1994

We have three rolls of 16mm black and white film that I begged from Kodak—then a phototechnical empire, today a shrinking giant from a bygone era. We have a Steadicam to use all night long.[2] It will give us a metaphysical look. We follow my manuscript with precision, but improvise when it is necessary. Nothing but the film matters to us this fall. I am employed at a national theater from which I have a monthly salary, which is so unusual in my field. At the theater, I find dancers, actors, costumes, a fog machine. I know when they are free and can book them in front of the camera. We are making our first film. I am responsible for the fog machine. The banana oil from it smells sweet. We just filmed in the basement with the Steadicam and scared my neighbors on their way to and from the shower and laundry room. Laila and I have splashed down the whole basement hall with water—her idea. She holds Joel by the hips so that he won’t fall when he walks. The camera is terribly heavy in this position. He uses headphones to listen to the music so he knows how slowly to walk. I hold down the button on the fog machine. The light fades through the fog and is reflected by the water on the surfaces of the hallway. The names of the lamps are not Par, Profile, or Fresnel; they are Redhead, HMI, and Blondie. Theater light and film light seem to be from different worlds, with unreality as a common denominator. When they reach the sign to the laundry room, Laila doubles the f-stop and freezes. She stops Joel from colliding with the bend in the hall. I let go of the button.

Excerpt from this scene in Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo: 0:00–00:29

Initiation into the field

My first encounter with the concept of dance film was at a seminar in 1994, arranged by Teater og Dans i Norden [Nordic Theater and Dance] at Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts. The invited speakers were Charles Atlas (USA), Walter Verdin (Belgium), and Vibeke Vogel (Denmark). For three days, we got to see Western dance film classics by Maya Deren; Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker and Walter Verdin; DV8 and David Hinton; Charles Atlas, Merce Cunningham and Michael Clark; Josette Baïz; Régis Obadia and Joëlle Bouvier; Magalie Charrier; Victoria Marks and Margaret Williams; Wim Vandekeybus and Iturbe; and others. At this seminar the speakers decided to announce the genre video dance, to put an end of the label confusions when creating artistic works for the camera. However, this word was not used for very long. Today, the genre is also called dance for camera, choreo cinema, media dance, or screendance.

The seminar made a deep impression on me, and it was at the very least a starting point for my own creations. I was 26 years old. I recorded my very first dance film on 16mm—without any technical film education, without any previous experience of film or video making—just a couple of months later in collaboration with Joel Olsson and Laila Östlund, students at the Academy of Film at the University of Gothenburg (now Valand Academy).[3] It was called Fröken Tuvstarr, hennes älskade och den skallige Quasimodo [Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo];[4] we worked with passion and frenzy, unconventionally and as equals. I was inspired by Maya Deren, Régis Obadia, and Joëlle Bouvier, and the house I then lived in. It was my manuscript, my choreography, directing, scenography, and costumes. They were inspired by Fritz Lang. It was Laila’s and Joel’s storyboard, cinematography, and lighting. The film premiered at the Gothenburg International Film Festival in 1995. That same year, it receive the mention spéciale at the international dance film competition Vidéo Danse Grand Prix "pour l’expression d’une univers personnel et la caractérisation des personnages." At that time only a few dance film festivals existed globally: Dance on Camera in New York City, ADF’s International Screendance Festival, a traveling festival called IMZ Dance Screen, and Vidéo Danse Grand Prix in France.

From the perspective of the Swedish dance community, however, people thought my film contained too little dance to be called a dance film, something pioneering female director Maya Deren had problematized 60 years earlier. The choreographer and dancer who create film often end up falling through the cracks, but these cracks are now well-visited and increasing in number. Because the film was in 16mm viewing format, however, it was not limited to dance film festivals. It could be shown at film festivals all over the world, in places such as Brussels, New York City, Bucharest, and Paris. The film gave me mobility and legitimacy. I met colleagues out in the world who worked like me. I took valuable courses in dance for the camera at the American Dance Festival at Duke University, in Madison, Wisconsin, and in New York City, all with Douglas Rosenberg; in Brighton, England with Miranda Pennell and Becky Edmunds; and in the one-year course entitled Fine Arts and New Media at the Valand Academy, with Mats Olsson. After I had made many videos, as well as my second film, The Dancer – a Fairy-Tale on 35 mm, a feature film combining dialogue and dance, I was even invited to join the network Doris for female film directors in western Sweden. But while the other members made “real” film, I made the deviating dance film. Katinka Faragó, Ingmar Bergman’s film producer, wrote to me, “You are so funny! Why don’t you forget about dance, and focus on dialogue?”

Excerpts from The Dancer – a Fairy-Tale, recorded in 1996

Gothenburg, October 1994

I stand in a room in the basement with the bald Quasimodo in the next room. The room is lit from outside.

Photo of HMI-lamps outside building, 1994 (in the photo: Laila Östlund). Courtesy of the artist.

The eyes of the lamps are pointed in from the mundane asphalt, the parking lots, the staircases, in through the window towards the magic of the basement. We each have our own personal doorman. Ex-boyfriends. They have received instructions from me about how to count. The cinematographers come rushing on top of the camera dolly, flying onto the track. They count, too, aloud so the doormen can hear. The doors to Miss Tuvstarr, whom I am playing, and the bald Quasimodo open simultaneously. Tuvstarr’s hair stretches all the way down to her knees. I am wearing a wig of linen that I sewed myself. Quasimodo is in a white silk tunic and thin sandals of brown leather. His name is Christian Fielder and he is strikingly beautiful. In realist films, he has played a villain, murderer, and policeman. Here, though, he becomes mythical, just like me. The concrete and plaster become painful gravel under my feet.

Photo of Quasimodo, played by Christian Fiedler, 1994, by Laila Östlund. Courtesy of the artist.

The cold gnaws at my bones. Tuvstarr and Quasimodo look up simultaneously on the assistant’s count. Their gaze sends the viewer into another room, under the roof, in the attic.

An excerpt from this scene, in Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo, begins at 00:29

The police come in the middle of the night while I’m rolling up cable. They shine their flashlights in my face. We have moved up to the attic, and the cables are stretched between the banisters, from the three-phase outlet in the basement up the entire staircase. I am in another element, in the dance; I don’t flinch, continuing to wind up the cable like Laila taught me. Carefully. “What are you doing?” the policemen ask, trying to sound serious. “We are filming!” I answer. They see the clapperboard and smile, retreating respectfully from the attic. We are a new trio working together. Me, Laila, and Joel. It is us, us, us. Where should we put the camera? The big room intended for hanging clothes to dry is now lit. I’m trying out my dance floor. Joel flies up to the rafters. “If you’re going to dance there, I’ll do a take from up here.”

Birgit Cullberg, the mother of Swedish TV Ballet

The pioneering works by Birgit Cullberg (1908–1999) and Måns Reuterswärd (1932-), made for Swedish television in the 1960s and 1970s, influenced the first generation of dance filmmakers in Scandinavia. As a teenager, I knew the scenes from Cullberg’s and Reuterswärd’s Abbalett by heart.[5] Because of technical constraints, Cullberg was compelled to develop ways of choreographing and composing for and with a single camera. For Cullberg and Reuterswärd, the space in front of the camera became a new stage, with the camera in the front row. We can see this as a site-specific experiment because in 1969, the Cullberg Ballet had neither stage nor studio of its own. Whole ballets were composed in the studio of channel 2 of the Swedish national television station (SVT), where Cullberg drew on the floor a perimeter the dancers had to observe. The picture was often framed with a dancing limb close to the camera. The audience might end up looking through an armpit, a foot or an elbow. What was important happened further away, in the middle of the picture, where the entire choreography was conveyed without actually abandoning the conventions of theatrical space.

In these films, dance was the central element and carried the meaning of the piece. Cullberg was clearly the originator and not simply playing second fiddle or working as an assistant, a role that Donya Feuer (1934–2011) assumed in her work with Ingmar Bergman, one which she escaped to create her own documentary The Dancer (1994).[6] Cullberg also experimented with new techniques and new camera angles. In 1971, Cullberg and Reuterswärd won the Prix Italia for Rött vin i gröna glas [Red wine in green glasses]. The dance film won prizes in the category for musical programs, which was not surprising, since both dance and dance films have historically been subordinated by music. In Rött vin i gröna glas, the dancers appear to swim forward through an oil painting. The dance is filmed from the ceiling in a blue room so that the background is changeable, in this case appearing as an oil painting. We approach the dancers. The movements give the sense of nearness, yet the dancers don’t leave the ground. In reality, we are viewing them from above, but the chroma key technique means that we believe we are looking at them from the side. After discussing the creation of the film with Måns Reuterswärd, I understood how Philippe Decouflé’s Abracadabra (1998) had been created.[7] Decouflé (1961-) also makes dance theater, but his dance idiom is vastly different from Cullberg’s.

Reuterswärd and Cullberg’s close collaboration with a television channel was unique for the time, and unfortunately no one has continued this practice in Swedish television production. Mats Ek’s ballets have been documented by SVT, but to my knowledge only Gammal och dörr (Old and Door, 1991), featuring a powerful 83-year-old Cullberg as protagonist, was created specifically for the camera—and SVT didn’t dare broadcast it until twenty-one years later.

The Filmmaking Dancer/Choreographer

What does it mean to be the filmmaking dancer, shifting between positions? In collaborations between dancer and traditional film director, there is a balance of structure and power. Can a dance filmmaker be the author, equivalent to a film director? What skills does s/he need in order to achieve that? This question gets especially complicated in projects where the artist contributes with his or her own specific craft to the piece, as when a choreographer also dances in his or her own film or a photographer directs his or her own film. Whose film is it, then? The film director is trained in both the instruction of people and the technical craft involved in photography. S/he is trained in teamwork, staging of filmic space, camera techniques, lighting, and postproduction. In Sweden, you can study film directing, but not film choreography, at the university level. This causes an insurmountable obstacle between film companies, film institutes, and the individual dance artist.

It is difficult to find continuity and depth when working with dance film. Ideas for dance films are disqualified already at the brainstorming session. An already very commercialized industry does not want to invest in experiments. According to the Swedish choreographer Pontus Lidberg, “Dance film falls through the cracks. The Swedish Arts Council refuses to support film, end of story; the Swedish Film Institute refuses to support dance, end of story. It is easy to refer to current practice and avoid taking a stand on dance film. After many years of persistent nagging, my films finally received support from the Film Institute, and this was only thanks to the facts that SVT was a co-producer and that the films were considered drama, not dance.”[8]

Film choreographers seldom have a background in film, nor do they have access to a technical education in film. In the course on film directing that I took in Gothenburg, taught by Reza Parsa, a male director of feature film, we learned filmic conventions and foundational skills. I was told that “art films” and “dance films” were what you did at the beginning of your career as preparation for “real” feature films. In spite of this advice, I made great use of the practical structures that I learned there when I was later making dance films. I used foundational skills like tripod-based camera approaches; close-up, medium shot, long shot, as are also used in dance film. What I learned in dance film courses—different experiments to capture choreography on film with a handheld camera—have been very important for my artistic choices, but not enough for communicating effectively with a film team. This is why I am somewhat critical of short courses intended for dancers who want to learn how to film. I would rather see a larger effort in which dance filmmakers are given the same chance as traditional filmmakers to engage with their art, where traditional filmmakers are no more or less important than film choreographers. We must not take it for granted that choreographers should be less accustomed to technology than directors, and also not ignore gender perspective behind these assumptions, where the traditional film field is dominated by men, and the dance film field is dominated by women.

Sometimes, the dance filmmaker moves between different practices, but in the process s/he ends up on the periphery of them both. I think that the field of dance often comes with a strict bodily regimen that can be difficult to rebel against, a bodily regimen that does not exist in the visual arts or among actors. I have been asked by my dancing peers more than once in my work as a film choreographer, “How do you keep up your physical strength and flexibility, how can you continue your dance practice during filmmaking?” My answer is usually, “I am a filmmaker when I film and a dancer when I dance.” I don’t think either Stephen Chow or Charlie Chaplin ever had to answer such a question. Eventually, a new practice should result, a dance film practice, possible to embrace and allowing us to be centered.

Today, more accessible and more mobile cameras are integrated into filmmaking, and the choreographer is physically and economically able to challenge the discourse of film production. We have seen many films from experimental studio processes where the camera functions more as a conversation partner than an observing external gaze, an approach that might be difficult to comprehend for someone outside the practice of dance. In these films we also see the dancer functioning as an originator who challenges the stereotypes that are easily created when dance in film is relegated to a pedestal. Sure, we love Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse, but other expressions are possible. Australian choreographer, dancer, and dance filmmaker Dianne Reid’s this could be the start of something is an excellent commentary in this context.[9]

Dance filmmakers develop their own strategies, structure maps, and storyboards. They use their own cameras and create their own festivals. Movements are composed for body, camera, and space, with separate phases of generating material and composing the film as a synthesis of creative and curating practices. How can we develop film terminology, finding new methods and idioms for framing dance on camera? This calls for further educational options or recurring advanced courses where dance and film artists, on equal footing and with pure curiosity, can have conversations about how to develop these methods. Where we can sketch out new versions of camera tracking, or ask how handheld camera improvisation can interact with tripod-reliant close-ups. A traditional film manuscript is complemented with drawings in the method taught at the traditional film schools. Distances, angles, and frames are categorized and named with words, words that are unknown to choreographers but essential for practical execution. We must invent a common language for dance filmmakers, create new accessible names for our own established methods, and make advanced techniques accessible to dancers.

Gothenburg, October 1994

The steps moving from behind the camera to in front of it are long and heavy. Cold feet inserted into hard, black sneakers. My frozen, stiff body in a black chiffon dress, with rhinestones around the waist, from a vintage shop in Manhattan. A Moroccan man in the shop next door helped me tailor it. As dancers we will need to have Marley-type vinyl flooring most of the time. I should make a note of that myself, at least, since I am the ambassador of dance. We will need carts for the cameras, and jibs. We will also need better floors in general. There is no one checking the safety of the work environment; there is only me, Laila, and Joel. We don’t work with reality. The industrial locations where many artists create their dance films are not hospitable. They are too cold. Too hard. But they are beautiful on screen. All too often the environment is used to convey a brutally beautiful aesthetic, but it might possibly be able to portray a human’s vulnerability. All too often the dancer is given the charge of taming these harsh spaces with her/his body.

Now we are no longer three. It is the two of them, looking at me. I see to the actors, the dancers, and the extras. But no one sees to me. I would rather wind cable, but I have to dance. They are waiting for me, they are finished. The lens is polished, the film gate brushed. I am the one who decided to do this but feel like a frightened deer in the headlights. Now I must dance. We are making a dance film and I am the one who will dance. Quiet on the set. The camera rolls. Clapperboard. Action. I run in and pretend that I am Joëlle Bouvier. I throw myself backwards into the chairs we set out as my track. The plaster and concrete fall apart, become small ball bearings under my feet. The air chafes my skin. My joints could burst into powder. We do another take. Joel’s feet hang down from the beam.

An excerpt from this scene, in Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo, begins at 01:17

Choreographing With and For the Camera Based on Nonlinear Treatment of Movement

The dancer’s perception offers a view of the world as more than just dance steps. The logic, energy, and events in a dance film can be difficult to define. There is no development, but the viewer feels that something is happening, something is recognizable in the dance. Another film: a wide shot is framed, sound: contemporary art music. The image remains a long time, causing the viewer to think of dance, or art, or murder. Contemporary art music is often imported to dance, to art and to crime stories. (What a destiny.) The camera looks out over a field. It is hand-held, and the movement of human footsteps makes you believe it is your own gaze. It is you who are standing there on the field. In the middle of the field is a rock; zoom in on the rock, run to it, keep running. Next to the rock lies a dead bird of prey; ten balloons are released into the sky. From far off on the right, ten people come. The way they walk reveals that they are dancers. Their bodies occupy space, stretch out. The dancer becomes a person who does not speak, one who is strong, and agile. There are no facial expressions no matter how anxiety-ridden these dancers may be. One of them rushes to the rock, remains there and begins to dance next to it. The other nine people continue on; the hand-held camera gives you the sense that you are walking along with them. A rocket goes off in the distance, in the same direction they came from. A metaphysical gaze in the form of a Steadicam sweeps over the field and the people. We sense a dramatic contour: empathy, fear, and flight. The story is told in such a way that it seems to be a never-ending cycle, one we don’t analyze or criticize, one we simply live in the middle of, one that may never change.

We can say that every movement in the above example of the fictional manuscript is musically choreographed. The different spaces are made rhythmic by the choreographer according to an existing musical phrase. Camera movements and shots are written into the manuscript from the beginning, because in this context they can be considered choreography and not only as a planned cinematography. But imagine that the dancer casts off his or her dancer persona, and enter into the film not as an aesthetically heightened dancing body but as a person who is heading somewhere, who has a name and who just happens to enter into conversation with someone along the way. The conversation might be with or without words. The dancer wants to make this predetermination impossible, to turn toward that which is not yet categorized. The result can be very exact and readable for the collaborators, but institutions like the Swedish Film Institute seem to lack this special kind of literacy.

A house can be a manuscript. We find characters inside the walls, in the basement, and in the attic. If the choreographer is already used to working with film, s/he has probably created a choreography that will tolerate being edited. It isn’t dependent on unity and shouldn’t be claimed to be a singularity. The editor is hesitant with the scissors at first. Shouldn’t the logic of the body be followed? Isn’t the order of steps important? The carefully planned and executed rhythm, should it really be tossed out the window?

When I show dance film to theater directors, I get commentary that I never hear from dancers. Some of it is pure misunderstanding. I like these misunderstandings. I think they are valuable in that they challenge our internal gaze, our bodily field: “They breathe, stand so straight, look past each other even though they touch each other. It is self-centered. Where are the relationships? Why don’t they communicate? Is dance afraid of clarity?” One could blame the strong theatre discourse: the need to define relationships and make things understandable. Particular actions, a solution, catharsis. Centuries of theatrical narrative have made many of us blind to other types of narrative: an act-free, scene-free narrative, as if dialogue were to dance. I read dance film via the body and interpret spinal movements more than I interpret gazes. Spinal movements need not in themselves say anything, but they communicate human experience and the condition of being.

Nevertheless, these questions from outsiders have helped me to realize something: film can reveal the theatricality of dance. Exactly as actors’ theater voices need to be toned down for film, the toning-down of physical energy can be necessary. The need to cast off the dancer persona, which on film is read as something other than a graceful stretching of the back, lengthening of the neck or raising of the knee. On film the dancer persona can become violent and self-absorbed. Is this really the intention? I have seen it happen myself. Dance film can mean objectification and fetishism of the event of dance. A profusion of flexibility and strength is one thing on stage and another thing on film. Think of all unreflective dancing male-female pairs in which we seem to forget the world order we live in, with all of its mundane symbols. In this discussion we invalidate the dancers. What happens if we take them seriously? Who oppresses whom, who throws whom, who tugs on whom? If the answer is always that dance shouldn’t be read in this way, that it is “just” dance, haven’t we put blinders on? If we look at it as pure, untranslatable art and repeatedly claim that this is all we see? All this because we have had to defend ourselves against overzealous interpretations that we fear may diminish the art of dance.

I long for a different kind of representation, like DV8’s last performances, comprised of political conversations spit out in the middle of the movements. Isabel Rocamora who turns the war in Iraq into dance.[10] I long for more politics and less aesthetics, less fetishism. I want to see dancing humanists, dancers who are activists. I want to meet the dancer as a person, with and within the complicated and complex dramaturgy of dance.

My first dance films were shown internationally at traditional film festivals because they were on 16mm and 35mm film. At these “film” film festivals, I escaped being seen as a dancer, being read as an aesthetic body. My dance film was read as “film” film, though it was naturally placed in a special category: “New Media” or “International” or “Music.” I answered questions about my homeland, about politics, about Ingmar Bergman, about all sorts of things that had nothing to do with my body. I experienced the enormous freedom to escape the stereotypical confines of my field.

Gothenburg, 1995

The 16th annual Gothenburg International Film Festival. Our premiere. We were consumed by love. But also hate. It was shocking, actually. We were blissful newbies; we could hardly stand, we were so excited. The auditorium of the Haga Theater was sold out. I gave splendid interviews. Answered questions. Talked about dance film, non-linear storytelling, ducked out, got up, tried to go forward but ended up talking and walking in circles. Lost the toes, landed on the heels. Referenced John Bauer.

Further excerpts from Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo

Female journalist 1: “Why make a film like this?”

Because …

Female anthropologist: “A female search for identity?”

No. It’s more of a fairy tale. A mix of fairy-tales.

Female filmmaker: “Yes, well does the Film Institute like this stuff?”

Don’t know.

Female journalist 2: “You dusted off your dance shoes and went for it!”

No, they didn’t need dusting off. They are always on. But I understand that you want to write this; it sounds more journalistic.

Male sound designer: “Does she laugh at men?”

No, she laughs for herself.

Bosses who want to eat dinner, just with me. Yes, it’s true.

“Incomprehensible. But beautifully filmed.”

Male film festival grand marshal: “My three-year-old liked the breasts.” Ex-boyfriend: “My friend saw it in Lund. He thought it sucked but said you’re really hot.”

I retreat to the forest. Climb barefoot up the slippery trunk.

Female teacher: “Like Hugo Simberg’s Injured Angel.”

Yeah, maybe more like that, but 1990s-style. John Bauer. Arosenius.[11]

Male critic: “Postindustrial symbolism.”

Symbolism we laugh at.

Female critic: “An ironic play on images.”

Ironic is the wrong word. As if we laugh while we are dying.

We want to return from the panic of whether or not the film exists. The frenzy of formulation, the belief in what is written, spoken. Thoughts collapse, the ability to infer. We can’t reach conclusions. We want to exist and continue to work—and only that. We want to return to the composing, and rolling up cables. There, we find identity. We want to return to the cables, the lamps. Our tools and friends, our practice.

Today I understand that the grand marshals of film festivals and many of the journalists lacked the necessary tools for reading dance. They were even provoked by the wordlessness. They were confused by concepts, weak-kneed. Outside of Sweden, people knew Maya Deren; they had a frame of reference. I sat in the New York Public Library and watched reel after reel. I clearly identified with Maya Deren. More Maya Deren than the symbolist painters Simberg, Bauer, or Arosenius. Many years later, I see Tove Skeidsvoll, playing a forest sprite in her and Petrus Sjövik’s film Outside In (2011). The camera approaches her; the film emphasizes the fictionality of the birch forest. We know that we are in a studio, that everything is made up. We begin to see black-robed, cable-rolling people beyond the trunks and fog machines. Then Tove goes on the attack. She leaves her forest, the universe she had been assigned to, and runs outside of the frame. She takes action while the technology clumsily retreats to the walls of the studio. An artists’ reclamation of space before technology gets it all.

Twenty years have passed since I made my first film, Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved…, and as I watch it again I realize that the film itself, the final product, is of less importance than the actual work: the honest exploration that we did together as equals.

Choreographing Non-bodies through Film: Creating Dance from Abstract Motion, Expanding the Scope of both Dance and Film

How can one categorize a dance film? As a practitioner, I think classifications are very helpful, but I often have an allergic reaction to them, and a fear of definitive statements, because in my practice I am not trained in argumentation. This sort of training has been completely absent from my artistic education, but I also often feel that things escape me as soon as I categorize them. I think it might be the issues around curatorial demands that I sometimes have wanted to revolt against. I will try anyway. If we compare performance documentation with original work—that is, if we look at a film of dance that was created for the stage and dance that was created for and in relation to the camera—we see obvious differences in intention and execution. Documentation can hardly be called film, yet this has been a category at dance film festivals. The English dance company DV8 Physical Theatre, under the direction of Australian Lloyd Newson, made both early on. Of thirteen performances, five have been adapted as dance films to the great pleasure of all who cannot make it to their theater in England. The adaptations use the same dancers, manuscript, choreographer, and music, but the performances have been completely re-created specifically for the camera.

We can also compare Cullberg and Reuterswärd’s TV-ballets with Wim Vandekeybus and Walter Verdin’s dance films. In the former, for example in Fröken Julie (Miss Julie, 1984), we see the choreography as it would appear in theatrical space, as if we were sitting in the audience. In the latter, especially in Roseland (1990), space is dissolved and we as viewers are not introduced to a consistent front. The dancers fall in and out of the picture. The camera constantly shifts its point of view. This is where the traditionally educated editor might get confused. The medium of film inserts itself in a way that it doesn’t always have the opportunity to in a traditional feature film. In this case, dance film is a clear example of how dance and film enrich each other. There is no doubt that it is dance, that the actors are dancers, and that a choreographer has created the movements in and for that exact space.

As we look at the 2000s, the questions get more complex. David Hinton’s Birds (2000), which won accolades at Dance Screen Brighton, raised discussion of re-editing existing films—in this case, nature films with birds—into new choreographies, using birds as unsuspecting soloists. He was re-choreographing the pre-choreographed, so to speak. His dance film was completely without dancers but was still wholly based on movement. The cuts and the music signaled the work of a choreographer, while the unrepeated movements of the birds gave the sense of dance. Another point of the discussion was the question of whether the film’s creator must be a dancer. To this, my answer is no. I see many examples of visual music films (Mary Ellen Bute, Norman McLaren, Len Lye) as dance. Visual music is not a new genre but perhaps was considered new to the context of dance film at IMZ Dance Screen, so again, it was a case of curatorial framing. When what is categorized as “visual music” can also be called “screendance,” it is the boundary-crossing itself that is important. We re-categorize and re-formulate genres in order to expand the field and to welcome new viewpoints and interests. But I still want to require the continued presence of dance in dance film. Dance should not get labeled “dorky” and fade from the field. Make dance films about birds but continue to be curious about dance of all sorts: ugly dance, “dance” dance, new dance, old dance, conceptual dance.

What does it mean to apply a choreographic eye to the world, capturing motion and calling it dance? This happens in Liz Aggiss and Joe Murray’s film Beach Party Animal (2011), which invites abstract motional thinking and portrays the world as a moving sculpture. The camera discovers and determines new angles. Whole Ferris wheels are thrown out into space and we cannot see if they are fixed or if they and their passengers are slung away for eternity. Camera angles and cuts make existence rhythmic, just as in choreography. Guerilla dancers appear as soloists on a beach. In one scene, the floor underlay finally affects the human body. There is no aesthetic enhancement in the glass-eating man who struts forth over the rocky beach, but rather burlesque comedy—a characteristic I recognize and love in Liz Aggiss’ work. In Beach Party Animal, an alternative vacation life is portrayed, a post-industrial Jacques Tati. The film rewords deeply human traits, aesthetic ideals, social class, the desire to leave cares behind. Naturally, it is a dance film, with the added benefit of the humor and musicality of honorary doctorate and dame of dance film Liz Aggiss.

The appropriation of dance films into meta-dance films can also be a way to choreograph non-bodies with the help of the filmic medium. I do this, for example, with my own experiment, Tåskor – Transparent – Talang (Toe Shoes – Transparent – Talent, 1997), splicing together and cutting apart the dance and ballet films I grew up with.

Toe Shoes – Transparent – Talent, 1997

I searched for the mantras I had forced myself to abide by as a practitioner: “Such a body has no place in ballet,” pronounced by Natalia Makarova in a documentary about ballet, but repeated in another context—Bollywood. In the making of the film, I highlighted different mantras so that even an outsider could relate to it and reflect on it. I had the opportunity to problematize different discourses in the field of dance that had previously been taken for granted—for example, what type of body belongs in an expression of dance? I treated the fetishes and symbols I had been fed with as a dancer: the objectification of the feet, the desirability of toe shoes, and the ideal dancer’s body. This experiment was done at an art academy, not a dance academy. I have met similar controversies in female video artists but incredibly infrequently in dance artists.

Excerpt from Talent, begins at 10:10

Though I now make more performances than films, film is still an important element in my stage work. Please look at these three clips from my recent performance 20xLamentation.

How can we embrace these different paradigms? In dance film education, different perspectives need to be presented, reflected on, and taken seriously. Should dance filmmakers claim dance as their field, or film, or neither? Should a dance filmmaker be educated differently than other filmmakers? Should s/he be trained to lead a traditional film team or to work alone? Must s/he be a dancer? With the emerging theoretical discussion and with specific educational opportunities directed at this genre, we can help dance filmmakers find a place in and between the established worlds of dance and film. I believe in giving these filmmakers a hundred opportunities instead of just two. I wish for policies at granting institutions that will make dance film possible, for film colleges that offer relevant programs. I long for a film industry that is truly interested in dance.

I am curious to see Richard Raymond and Akram Khan’s Desert Dancer, which will be released this year, about the Iranian dancer Afshin Ghaffarian who taught himself to dance with the help of YouTube, even though both dance and YouTube are forbidden in Iran. I also look forward to Swedish filmmaker Carl Javér’s documentary film Freak Out! (2014) about alternative movements in the beginning of the 1900s, with appearances by Mary Wigman and Rudolf Laban. I long for films that challenge the conservative language and bodily regimes of dance, that continue to refer to dance film history, and that accept more non-Western expressions. Shim Sham and Rosseuve’s Two Seconds After Laughter, in which we encounter self-reflective Javanese dance (Yogyakarta) in a contemporary context, is an excellent example. Or Brown and Patnaik’s Statues Come to Life (2012), where the ancient dance form Odissi becomes the main event. In 2013, my own documentary film on traditional Japanese dance, The Dance of the Sun, was released in Sweden (shown at the American Dance Festival on July 19th, 2014).

In 2013, a dance film festival was founded in Bandung in western Java by the choreographer and dancer Alfi Yanto. Thanks to this festival, I was able to participate in contemporary Indonesian dance film experiments and familiarize myself with the art and activism of WajiWa Bandung Dance Theatre. Recognizing the evolving field of screendance does help us look into what we have already recorded, and to document our present day for future use. It also helps us to encounter new choreographies in new geographies. It can give us exactly the nontraditional, alternative stories of the body that we need in order to dismantle our prejudices about the world, dance film, and ourselves.

Photo of Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt in the documentary film The Dance of the Sun. Courtesy of the Kyoto Art Center.

Media

A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945). Dir. Maya Deren. New York.

Abbalett (1984). Dir. Birgit Cullberg and Måns Reuterswärd. Stockholm: SVT.

At Land (1944). Dir. Maya Deren. Amagansett, Long Island.

A Moment in Love (1957). Dir. Shirley Clarke.

Beach Party Animal (2011). Dir. Liz Aggiss and Joe Murray. Brighton, UK.

Birds (2000). Dir. David Hinton. London: BBC.

Blue Studio: Five Segments (1975–1976). Dir. Charles Atlas and Merce Cunningham. New York.

Bridges-Go-Round (1958). Dir. Shirley Clarke.

Dance in the Sun (1953). Dir. Shirley Clarke and Daniel Nagrin.

Desert Dancer (2014). Dir. Akram Khan and Richard Raymond. London.

Enter Achilles (1996). Dir. DV8, Lloyd Newson and Clara van Gool. London.

Freak Out! (2014). Dir. Carl Javér. Gothenburg.

Fröken Julie [Miss Julie] (1980). Dir. Birgit Cullberg and Måns Reuterswärd. Stockholm: SVT.

Fröken Tuvstarr, hennes älskade och den skallige Quasimodo [Miss Tuvstarr, her beloved and the bald Quasimodo] (1995). Dir. Joel Olsson, Ami Skånberg and Laila Östlund. Gothenburg.

Gammal och Dörr [Old and door] (1991). Dir. Mats Ek. Stockholm: SVT.

Hail the New Puritan (1987). Dir. Charles Atlas and Michael Clarke. London.

La Chambre [The Room] (1988). Dir. Joëlle Bouvier and Régis Obadia.

La Lampe [The Lamp] (1990). Dir. Joëlle Bouvier and Régis Obadia.

Labyrinth Within (2011). Dir. Pontus Lidberg. Stockholm.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). Dir. Maya Deren. New York.

Monoloog van Fumiyo Ikeda op het einde van Ottone Ottone (1989). Dir. Walter Verdin and Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. Bruxelles.

Outside In (2011). Dir. Tove Skeidsvoll and Petrus Sjövik. Umeå.

Roseland (1992). Dir. Walter Verdin, Octavio Iturbe and Wim Vandekeybus. Bruxelles.

Rött vin i gröna glas [Red wine in green glasses] (1971). Dir. Birgit Cullberg and Måns Reuterswärd. Stockholm: SVT.

Statues Come to Life (2008). Dir. Bobby S. Brown and Devraj Patnaik. Ontario.

Synchromy No 4: Escape (1938). Dir. Mary Ellen Bute and Ted Nemeth.

Tåskor – Transparent – Talang [Toe Shoes – Transparent – Talent] (1997). Dir. Ami Skånberg. Gothenburg. http://youtu.be/p-aPuEHfqE0.

The Dancer (1994). Dir. Donya Feuer. Stockholm. The Dancer, a Fairy-Tale (1999). Dir. Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt. Gothenburg.

The Dance of the Sun (2013). Dir. Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt and Folke Johansson. Gothenburg, Kyoto.

The Rain (2007). Dir. Pontus Lidberg. Stockholm: SVT.

this could be the start of something (1997). Dir. Dianne Reid and Paul Huntingford. Melbourne.

Two Seconds After Laughter (2011). Dir. Cari Ann Shim Sham and David Rousseve. Java.

Under Pressure (2013). Dir. Alfi Yanto. Bandung 2013.

Notes

-

In the early nineties I had a hard time convincing the male Swedish film festival grand marshals that one could have more than one dance film in the program. ↩

-

Steadicam is a camera stabilized by a counterweight, thereby providing a smooth, fluid shot. ↩

-

I had some experience of acting in front of the camera, e.g. in a short film with the Swedish movie star Viveca Lindfors in New York City. ↩

-

Translator’s note: Although “Tuvstarr” means “hassock” or “bunch grass” in English, the author refers to this character by her Swedish name even when speaking in English. ↩

-

Abbalett was created for Swedish Television in 1984 to the music by the Swedish pop group ABBA. ↩

-

My own film The Dancer, a Fairy-Tale (1999) was a reply to Donya Feuer’s The Dancer, as an attempt to provide the audience with less conformist images of the ballerina. ↩

-

Discussion with Reuterswärd in New York, January 2000. ↩

-

Pontus Lidberg lives in New York City. He is recognized for his dance films Labyrinth Within (2011) and The Rain (2007). ↩

-

Dianne Reid, “this could be the start of something” (1997), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZg4RaEFyN0&list=PL5114E2A81B2E5016. See also her essay in this issue. ↩

-

Isabel Rocamora, British-Spanish filmmaker and choreographer, has made, among other films, Body of War (2010) and Horizon of Exile (2007). ↩

-

Swedes John Bauer, Ivar Arosenius, and Finn Hugo Simberg are symbolist painters from the turn of the twentieth century. ↩