Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space

Joséphine A. Garibaldi and Paul Zmolek, Idaho State University

While in residence Spring 2014 in Riga, Latvia we directed Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space, an international intermedial collaborative choreographic project between dance students of the Latvian Academy of Culture (LKA) and Idaho State University (ISU). This provided an opportunity to explore the collaborative possibilities of establishing a virtual community on the internet, where Latvian and American students could work together in composition by interacting online in real time in physical and virtual space. What resulted was a choreographic process and culminating event that existed in time and space in three simultaneous, interconnected performances—each containing elements of the other two. The web-streamed video performances captured the projected performances of live dancers on two different continents, creating an unending, self-referential performance loop. Each of the three simultaneous performance locations were different: in Riga, Latvian dancers performed with a live switched video projection of Latvian/US dancers; in Pocatello, Idaho, the US dancers performed with a projected video of the event; and the live switched video of the two cross-continental performances was available for public consumption on the internet.1 This article poses the initial concerns that formed the project, presents the process (providing links to YouTube recordings of each session), outlines some of our difficulties and discoveries, and explores some theoretical implications that emerged from Global Corporeality.

Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space

The primary intention of this project was to explore the potential of available consumer technologies to make intermedial dance work(s) that crossed cultural and international distances. Utilizing laptop cameras for input and projectors for output, the exchange was facilitated through Google Hangouts on Air, which was selected for the ability to broadcast live and record to YouTube.

Entering into the project our intentions were to:

- Continue to explore the limitations/possibilities of our creative methodology, which we call Dialogic Devising, in order to collaboratively create intermedial performance works

- Explore the possibilities of subverting commodified virtual community applications (in this case, we used Google “Community”) to build a corporeal and virtual creative community

- Model the utilization of ubiquitous consumer-level technologies for DIY (“do it yourself”) production of creative work for our students

- Create an international, intermedial work in order to bridge corporeal and virtual realms.

Dialogic Devising

As performing artists, our practice is based in the rich oral tradition of human-to-human interaction. Whether through real or virtual space, fostering productive collaborations to make work we consider meaningful is at the core of our art-making practice.

The roots of Dialogic Devising are pedagogical, developing out of content-based approaches2 we have utilized as artists-in-schools and as instructors for teaching methods courses. We draw inspiration from Paolo Freire’s theory of dialogic action,3 perceiving artists as agents of cultural change. Through dialogue and interaction with others, a creative community is created to solve problems through interactive play.

Through a dialogic process of research, brainstorming, writing, free association, creative writing assignments and exchange, we create text, which we then edit. We identify resonant words and then pair them through chance operations to terms connected to aspects of the elements of movement to manipulate body parts, movements, pathways, time, space, energy, and sound. By this process, performers create source movement physically integrating text rather than pantomiming text. Movement is developed through standard choreographic manipulations, taught to other collaborators, and then structured into a cohesive whole. Text is incorporated in either live spoken word or recordings within the sound score.

For many years, and more recently in digital space, we have been refining and expanding this creative method in various cultures and countries for trained as well as untrained dancers, actors, singers, and visual artists of different ages and abilities. While text is the starting point for our creative methodology it is considered an equal actor to sound, image, and movement. We allow words to be signifiers layered with other signifiers without necessarily providing a linear narrative.4 This layering of information is analogous to the online DIY tech environment where delay, low resolution, and low bandwidth may contribute to unavoidable “noise” through degradation of successive feedback loops and/or as additional devices are added into the process.

What we have also discovered is that dialogic devising resembles the very similar interactive hypertextuality of digital space where tangential ideas and additional information burst forth from many nodes of activity.5 Rather than presenting a linear narrative, the work (and the process) is multi-directional with multiple centers of activity filtered through varying points of view sharing space and time.

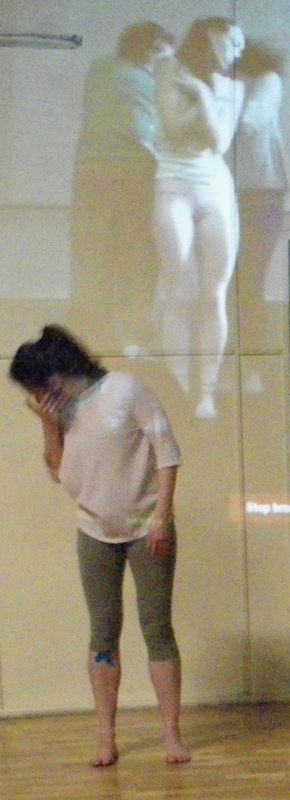

LKA dancers with projection of ISU dancer, image by Paul Zmolek

Collaborative Virtual Community

Community is typically anchored to a specific space and time by identification with place and collective narratives of individuals based in memory, perceptions of the present, and projections of the future. This is particularly relevant to the ontology of virtual community where the paradoxical relationships of the real, live, and mediatized share past, present, and future in the space of technology. Regardless of physical or virtual space, the essential characteristics of community include a sense of membership, shared interests, interaction, and reciprocity. Whether meaningful relationships are forged is entirely dependent upon the agreed upon parameters of the community and whether interactions occurred between individual members. Identifying an interaction as meaningful is complicated at best. Our assumption is that some sort of change has taken place in the space of the interaction. What is meaningful is determined within the space of the interaction. What is important is the in-between space and time where change occurs. As artists, pedagogues, scholars, and as global citizens, this is what is essential: how to collaboratively generate the making of communal work and, through that interaction, experience change.

Following Richard Schechner’s expansion of Victor Turner’s work,6 performance articulates the in-between transgressive spaces of structure/anti-structure. We attempt to foster an egalitarian sense of communitas amongst our collaborating performers with the hope that a liminal state may be attained and, as is true in efficacious ritual, the art may catalyze a transformation within the performers and/or the audience. Establishing syncretic creative communities that simultaneously exist in physical and digital space may assist these efforts. In digital space, the “‘inbetween’ space of intermediality”7 presents a liminal space of performance.8

The Process9

We recruited four students from Idaho State University (ISU) who had experience in our devising method. Latvian Academy of Culture (LKA) assigned eighteen students to participate in the project. Each institution provided dance studios, a video projector, amplification/speakers, online access and some technical assistance. Without dedicated camera operators or adequate cabling we decided to use laptop-based cameras instead of external camcorders.

We met as a group online for a total of eight two-hour collaborative sessions and one culminating event. Each session consisted of three performances occurring simultaneously in Pocatello, in Riga, and on the internet.10 The culminating event in Riga was documented with a separate dedicated external camcorder.

In order for us to interact online, we established a Google+ environment, including a newly formed private Google Community and Google Drive, which provided cloud space for sharing text, audio, photo, and video files.11 After introducing the Google+ environment, the theme of ‘communication’ was suggested as the starting point. To flesh out the theme, we began with a brainstorming session free-associating the concept and phenomena of communication and creating a list of the words and phrases from which each participant chose eight significant words.12 Significant words are defined as those metaphoric words that resonate with multi-layered meanings and, for whatever reason, are attractive to the participant. The selected words became our final distilled list from which we would generate the source material for ‘communication.’13

From this reduced list, students were asked to create a four line ‘rhythm verse’ with each line including one of their significant words loosely following the structure of the Daina,14 the traditional Latvian folksong. Additionally, students were asked to write freely ‘what is significant about the word’ and to provide visual context, students were asked to post one photo that evoked their ‘sense of place.’ From the significant words and the ‘sense of place’ pictures, devising prompts were provided to generate movement material. The students were then asked to record audio and/or video vocalizations of their ‘rhythm verses’ using readily available software (e.g. GarageBand, iMovie, etc.).

During the second session, the students explored the medium through improvisational prompts that facilitated physical and virtual interaction with each other. At ISU, with only four collaborators, two laptops were placed in stationary positions in the studio. At LKA, one laptop served as the live switching bay. As the improvisation continued, dancers added additional devices—laptops, tablets, and smart phones—to the Hangout, providing multiple points of view that had rich artistic potential. Of particular interest were the shots that included live dancers, projected dancers, and the image of both in the studio mirrors.

After this session, the ISU dancers commented they felt frustrated in their attempts to develop meaningful improvisations with their international partners because the image would switch in what they felt was a very short time. To develop their improvisation they wanted the image to stay with their partners rather than switch to themselves. To best facilitate the internet performance however, switching needed to occur on a relatively quick basis to highlight the various activities that were occurring, as well as create choreographic layering between the live and projected dance. To facilitate the interaction for the dancers, then, it would require much slower switching that emphasized the action in each respective remote site.

In contrast to our typical creative process based in numerous private rehearsals prior to public performance, all sessions of Global Corporeality were publicly streamed via Google Hangouts. This performance of process complicated the on-the-fly editing or switching decisions for the Hangout audience that were, at best, a compromise. The purpose of Global Corporeality was to use the technology to bridge international distances and make work collaboratively and physically in real time facilitated through meeting in digital space. The seduction of the image of mediatized bodies, the self-imposed pressure to satisfy both present and future audiences, and the need to use the technology to directly support the collaborative process were always at odds with each other.

As we continued to work, we found that time was necessary to facilitate the choreographic process. Contrary to the accustomed ‘high speed’ internet, the corporeal interaction via internet was extremely slow. Participants needed to speak slowly while articulating their speech. The space between dialogic call and response expanded as we allowed for delay and lag to settle. To compensate for small screens and limitations of the cameras’ depth of field, full body movements were translated into gestures transposed to hands and fingers. All of us had to temper our frustrations, mindfully and intentionally exercising patience with the process, the technology and each other.15

Facilitating the Collaborative Virtual Community

Global Corporeality continued our investigation into the possibilities and limits of Dialogic Devising, which we have previously employed with trained and untrained dancers from various backgrounds in the United States, Italy, and Finland.

Any collaborative effort requires the participants’ trust in each other, trust in the process, and trust in the director(s). We have found that developing trust from participants who are accustomed to more traditional authoritarian, single-author creative processes often takes time even in face-to-face interactions. This is compounded when the director of the venture is a guest artist from a different culture.16

Projection from Hangout session on LKA student’s face, image by Taisija Frolova

The larger group in Riga made it easier for the less outgoing members of their group to ‘hide’ and more difficult for the four ISU participants to develop relationships with each of the LKA students. Though all the Latvian students spoke and wrote English at a competent level, their first languages were Latvian, Russian, Norwegian, and Finnish.

Participants reported that they felt the nine-session project would require more time, perhaps up to a full year, to fully develop a sense of trans-site community. Few participants actively engaged in the opportunity to develop relationships outside of the scheduled sessions through interactions on Google Drive despite the efforts of a couple of participants. Some of the students began to use their already established personal Facebook pages to facilitate communication between collaborators. The Google+ site provided several very useful communication tools, but it did not provide access to personal details made possible by Facebook ‘friending.’

Online communities typically consist of isolated individuals sitting alone at their keyboards connecting through cyberspace with other isolated individuals. Global Corporeality attempted to create one community of two separately sited groups. With the LKA group the difficulties of attempting to utilize technology designed for individual interface were clear: only one person could be actively engaged while the other seventeen crowded around the 13-inch screen to see the ISU participants, which severely limited full-body involvement. Projecting images of the overseas collaborators created a desire to dance with the images on the screen that, in effect, turned their backs to their differently-sited dance partners. As previously noted, employing multiple devices allowed the LKA students the opportunity to participate as camera operators framing multiple points of view, however this pulled them out of a full-bodied interaction to collaboratively create the movement.17

The first sense that a LKA-ISU community was being created occurred after the break-out sessions where small groups taught their movement to each other. Smaller groups facilitated greater intimacy between participants; they could be closer to the device that served as the portal for dialogue, they could see each other, hear each other, and so on, and experienced reciprocity more directly. This is when the use of multiple devices to host different Hangout sessions was particularly effective. Whereas scheduling more than one session per week and/or utilizing a more familiar social networking application may have encouraged more connections to be created earlier in the process, the fact that the dancers seemed the most fully engaged in the embodied experience of teaching and learning each other’s movement is unsurprising.

The LKA students had a different experience than the ISU collaborators. The large group in Riga was responsible for dancing, choreographing and creating rhythmic scores. The small group in Idaho had the additional responsibilities of facilitating the technical aspects of their site. While the ISU students were sometimes distracted away from the dancing by having to trouble-shoot the video and audio, their involvement in the technical aspects of the process led to several suggestions for staging the movement that made best use of the cameras and the projection of the digital image.

LKA dancer with projected ISU dancers, image by Paul Zmolek

We were very pleased by the ability to extend the range of our creative devising methodology through Google Hangouts and social media. However, it is doubtful that the collaboration would have been as fruitful without collaborators who were familiar with our method of Dialogic Devising.

We observed that there were varying levels of engagement amongst the individual participants at each site. Whether selected by audition, invitation, appointment or self-selection, the effort invested by collaborators in remote sites of corporeal collaboration via the internet is essential.

To strengthen the collaboration, the issues regarding scheduling of sessions, staffing, initial training and bandwidth would need to be addressed. Social media (e.g., Facebook) could be used to hasten the process of developing trust and communication between participants.

After the project several LKA students went on to create their own sound scores for their personal choreographies. The 3rd year curriculum at LKA limited the use of video within their own choreographic works until the following year so we are unsure of how much they absorbed from this project. ISU collaborators, who have previous experience working within our intermedia projects have already created their own projects using variations upon our creative methodology and consumer-grade technologies. Some of the students have maintained and developed the international connections forged through this project. Time will tell if they pursue future collaborations.

Conclusions

Global Corporeality was an exploration of whether our method of Dialogic Devising could be successfully applied by utilizing technology to merge two existent physical communities in separate locations into a third community in mediatized virtual space.

Online communities created through social media consist of individuals interacting in multiple cross-referenced interactions or nodes facilitated by a web of interconnections. Community members act simultaneously as observers, participants, producers and critics of the multi-networked content. To make use of the potential of the technology an internet dance community should likewise have a web-like structure, consisting of multiple individual producer/consumers collaborating as choreographer/dancer/videographers. For Global Corporeality, the technology provided portals for two-way communication between two groups, a higher tech version of the children’s game of playing telephone with two cans on a string.

The Global Corporeality community we created only existed because of the in-between space that virtual space provides. This virtual community is no less real than the community gathered together to participate in the ritual of rehearsing in the studio. The community ties are forged through the process of dialogic devising where we create and recreate versions of ourselves through text, image, movement and sound. What results is a real, physical Barthesian sense of presence, where real is present in the image of the mediatized body.18 What is real has less to do with corporeality and more to do with time and space. The mediatized is real in as much as the real is real, only different.19 Questions of real in philosophical treatises that imply questions of what is meaningful or not seem somewhat moot to practitioners of digital/real syncretic performance. Simply put, the ontology of the real, live and mediatized has evolved beyond the spectre of the simulacra.

Live streaming is the live broadcast of an actual event; on-demand viewing provides a record of an actual event available for later viewing. In discussions of what is live and what is real, time is the centerpiece. Whether it is live or mediatized is not the issue. According to Steve Dixon, “In phenomenological terms, it must be agreed that liveness has more to do with time and ‘nowness’ than with the corporeality or virtuality of subjects being observed.”20 Dancing with a mediatized body in virtual space is no less live than dancing with body in physical space.21 This suggests that digital performance also has real, physical consequence. Digital performance will not replace live performance as the new “liminal norm”22 of performance, rather it offers opportunity to expand what the normative may be.

On demand viewing of screendance implies the reproduction of the mediatized body for the visual consumption of the viewer. That is not to say that the visual image does not have presence, rather, it has become an end product meant for consumption. This assumes that screendancers, in an expression of late capitalist post-modernity, capitulate to the post-human condition where mediatization reduces agency to consumable product. Global Corporeality strove to fully exercise active agency by subverting commodified virtual community applications through the building of creative community that functioned both corporeally and virtually. Rather than presenting a fractured identity that is most often characterized by virtual reality and post-modernity, Global Corporeality was able to unify and mobilize one collective whole made possible through the available consumer technology and the multi-directionality and multi-nodality of virtual space.

Global Corporeality is just a starting point. It demonstrates the potential for using internet video/sound/social platforms for facilitating and staging remote site collaborations. Creating a collaborative community via the commodified Google+ space where all information is shared/sold and data is mined to capture the consumer presented concerns not normally confronted when devising solely in real time and real space. We are intrigued by how performance is being redefined through the simultaneous acts of gazing and submitting. The instant record/replay/feedback loops made easily accessible by Google Hangouts on Air that becomes instant (re)surveillance of one’s own activity and self-reflection works simultaneously as public reflection. After returning to Idaho in October 2014, we began facilitating Laptop Performance Laboratory (LPL) to continue exploring this work. With two participants in Idaho and individual collaborators located in England, Finland, and Latvia, LPL will hopefully avoid the problems created by large groups noted above and, through the utilization of individual interfaces, make more use of the potential of the medium. We are excited to continue exploring the possibilities and invite you to join us: http://callousphysicaltheatre.weebly.com/laptop-performance-laboratory.html.

Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space was made possible by the generous support of the Fulbright Foundation, the Institute of International Education, the Council for the International Exchange of Scholars, the Latvian Academy of Culture, and Idaho State University’s College of Arts and Letters, School of Performing Arts, Oboler Library, Instructional Technology and International Programs Office. Special thanks to Maria Fletcher, Kandi Turley-Ames, Laura Woodworth-Nye, Thom Hasenpflug, Olga Zitluhina, Ramona Galkina, Krzyzstof Szyrszen, Ingrida Bodniece, Ingrida Grauze, Ryan Faulkner, Kristi Austin, Kent Kearns, Lisa Kidder, Mark Norviel and Uldis. Most special thanks to our collaborators/emerging artists: Latvian Academy of Culture Department of Contemporary Dance - Rûta Pûce, Agate Bankava, Ivars Bronics, Anne-Birthe Nord, Alise Putnins, Janis Putnins. Martins Spruds, Maija Tjurjapina, Anastasija Lonsakova, Anna Novikova, Rudolfs Gedins, Agate Cukura, Taisija Frolova, Eva Kronberga, Sandra Lapina, and Karina Lapaina; Idaho State University Department of Dance: Bridget Close, Julie Leir-VanSickle, Hannah Matsen, and Danielle Essma.

Biographies

2013/2014 Fulbright Scholar in Latvia, Joséphine A. Garibaldi devises original transdisciplinary and intermedial performance works, environmental and site-specific installations, video, photography and sound scores. Co-Artistic director of Callous Physical Theatre, since 2004 CPT has produced over 20 original performance, installation and digital works including Stories from the Park, Grass is Green, and LIVE in Riga, Latvia; The Rule of Life and Appartengono in Assisi, Italy; Cagevent: Sometimes it works, Sometimes it doesn’t Helsinki, Finland; the contemporary opera Double Blind Sided and the permanent 5500' environmental installation Birch Loops in Hameenkyrö, Finland. Garibaldi is former owner/director of Barefoot Studios in Tacoma, WA garnering the Margaret K. Williams Award for Excellence in the Arts and AMOCAT Award for Arts Outreach. Garibaldi and Zmolek directed Omulu Capoeira Performance Group in San Francisco and founded Omulu Capoeira Sul in Los Angeles creating collaborative works with masters of Taiko, Flamenco, Kathak, Capoeira, and Congolese dance.

Paul Zmolek is an award-winning interdisciplinary dance artist/educator whose dance/theatre/opera/performance/video/sound/ installation works have been featured throughout the Western US as well as Latvia, Finland and Italy. As co-Artistic Director of Callous Physical Theatre, Paul collaboratively devises physical theatre based in choreographic craft. Past work includes collaborations with masters of Capoeira, Kathak, Flamenco, Taiko, Congolese and Chinese dance and music. Highlights of his performance career include creating title roles for the world premieres of three Frank Zappa ballets and performing in works by Paul Taylor and Anna Sokolow.

References

Auslander, Phillip. “Digital Liveness: A Historico-Philosophical Perspective.” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 34.3 (2012): 3-11.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Barton, Bruce. “Paradox as Process: Intermedial Anxiety and the Betrayals of Intimacy.” Theatre Journal 61.4 (2009): 575-601.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Anthology, edited by Steven M. Cahn and Aaron Meskin. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 327–343.

Crandl, Jodi and G. Richard Tucker, “Content-Based Instruction in Second and Foreign Languages.” Foreign Language Education: Issues and Strategies. Eds. Amado Padilla, Hatford H. Fairchild and Concepcion Valadez. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990.

Dixon, Steve. Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art and Installation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

“Fisher-Price PXL-2000”, Total Rewind. Accessed 30 July 2014. http://www.totalrewind.org/cameras/C_PXL2.htm

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 2nd Ed. Trans. Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Continuum Books, 1993.

Garibaldi, Joséphine A. “DANC 4485 Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space”, Faculty Website. Accessed 30 July 2014. www.isu.edu/~garijose/Pages/Course%20Syllabi/LatviaGlobalCorporeal/Global2014

Garibaldi, J. & Zmolek, P., “Global Corporeality”, Callous Physical Theatre. Accessed 23 July 2014. callousphysicaltheatre.weebly.com/global-corporeality.html

____. “Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space: 3 Feb 2014:1.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “let’s go!” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space: 10 Feb 2014/Exploring the Medium.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “17 Feb Collaborative Choreography: Developing Source Material.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “24 Feb Collaborative Choreography: Corpo-Reality.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “3 March Collaborative Choreography: Rhythm Verses.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “10 March Collaborative Choreography: Phrasework.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “17 March: Day of the Irish.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “31 March: Dancing for Jean Arlene.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

____. “LIVE - Global Corporeality: Collaborative Choreography in Digital Space.” Dir. Joséphine A. Garibaldi & Paul Zmolek. 2014. YouTube.

Jackson, Shannon. Professing Performance: Theatre in the Academy from Philology to Performativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Kester, Grant. The One and the Many: Contemporary Art in a Global Context. Duke University Press, 2011.

Kozel, Susan. Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Landow, George P. Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 1992.

Latvju Dainas: Latvian Folksongs. Interlinear Translation, Ed. Krisjanis Barons. Latvia: LU LIteraturas, Folklorus un Makslas Instituts, 2012.

Lehman, Hans-Thies. Postdramatic Theatre. Trans. Karen Jürs-Munby. London: Routledge, 2006.

McKenzie, Jon. Perform or Else: From Discipline to Performance. London: Routledge, 2001.

Oddey, Alison. Devising Theatre: A Practical And Theoretical Handbook. London: Routledge, 2010.

Piorkowski, Geraldine K. Too Close for Comfort: Exploring the Risks of Intimacy. New York: Plenum Press, 1994.

Prager, Karen J. and Roberts, Linda J. “Deep Intimate Connection: Self and Intimacy in Couple Relationships”, The Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. Eds. D. Mashek and A. Aron. Mahwah, NJ: Ehrlbaum, 2004. 43-60.

Salter, Chris. Entangled: Technology and the Transformation Of Performance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010.

Schechner, Richard. “From Ritual To Theater And Back: The Efficacy-Entertainment Braid”, Performance Theory. London: Routledge, 2003. 112-169.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction, 2009.

Notes

The default setting for Hangouts automatically switches video to accompany the dominant sound source. We opted to manually switch by clicking upon the in-screen windows that display each source.↩

See Crandl and Tucker, 187. Content-based dance pedagogy derives from the cross-disciplinary teaching methods developed by language educators.↩

See Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.↩

Dialogical devising can be seen as a variation of postdramatic theatre. See Hans-Thies Lehman’s Postdramatic Theatre, for an excellent exegesis on this tradition.↩

See Landow, Hypertext.↩

Richard Schechner’s “Entertainment/Efficacy Braid” connects Theater and Ritual form while differentiating their intentions. Schechner maintains that ritual must have real, irreversible actions. Victor Turner questions whether industrial/post-industrial societies can actually go from liminoid to liminal and truly have efficacious rituals.↩

Barton, “Paradox as Process,” 575-601.↩

For this project we contented ourselves with exploring whether this technology could effectively facilitate collaborative dance-making. The question arises remains whether virtual, entertainment, consumer-based technology can facilitate a liminal state leading to efficacious ritual performance. For this project we set our sights somewhat lower, striving to explore whether this technology could effectively facilitate collaborative dance-making.↩

For access to video documentation of Global Corporeality, go to http://callousphysicaltheatre.weebly.com/global-corporeality.html↩

The three performances were live, occurring simultaneously in time yet, due to the delay created by non-instantaneous transmission of images and sound through the internet, each performance was concurrently in present and past tense. These simultaneous past/present corporeal/digitized performances present an interesting paradox when one considers the definitions of “live” performance. See Dixon 127-130 for a concise discussion on the phenomenology of liveness.↩

You will need a Google+ profile and permission to enter this site: https://plus.google.com/communities/112911744546209856759?partnerid=gplp0. For permission, please email: ↩

For this project we did not make any attempt to correct perceived misunderstandings, mispronunciations or cultural “lost in translations.” What was uttered was what was used. For example, one choreographic section was built on the misspelling of “misunderstanding” during our brainstorming session. What was written down was “miss understanding”; the section we built, then, was named Miss Understanding. Another example was the pronunciation of “gibberish.” In American pronunciation, we pronounce with a soft “g.” One of the LKA students pronounced gibberish with a hard “g.” What resulted was gibberish with a hard “g” utilized within a lyric for a song that the performer composed and recorded for her dance composition—a perfect solution evoked for the word gibberish.↩

For a detailed description, you may view the course website: www.isu.edu/~garijose/Pages/Course%20Syllabi/LatviaGlobalCorporeal/Global2014.html↩

Latvian folksongs are short. They typically appear as four-foot trochaic quatrains. Occasionally the dactylic meter is used. For a very valuable resource, see “Latvju Dainas,” 14.↩

Due to limited bandwidth and screen space on Google Hangout, we decided to de-emphasize the exploration of multiple points of view and instead focused on using the technology as a portal for communal and corporeal interaction. This provided time for student collaborators to work more directly with each other online to develop their choreographies.↩

In our 2011 collaborative project Appartengono (A Sense of Belonging) with the tiny community of Costa di Trex outside of Assisi, Italy, we felt that the participants did not fully trust us and the process until the last meeting before the exhibition of the work. http://callousphysicaltheatre.weebly.com/appartengono-ginestrelle.html.↩

When wearable devices akin to Google Glass become cheap and widely used it is conceivable that isolated individual collaborators could function fully in a virtual screen dance community. Until then it seems that the ideal staffing would be to have several small cells of dancer/camera operators which would allow each participant to actively participate both corporeally as dancer/choreographer and virtually through the digital interface, thus providing perspective as active object/subject.↩

See Barthes, Camera Lucida.↩

Dixon, 127.↩

Ibid.↩

See Kozel, Closer, 213-268.↩

McKenzie, Perform or Else!↩