Imagined Archaeology and Enlivening the Proximate Senses in the construction of Blind Torrent – An Interdisciplinary Screendance Project

Ruth Way, Plymouth University

Russell Frampton, Plymouth College of Art

Abstract

The screendance project Blind Torrent, is the result of an ongoing collaborative and interdisciplinary film making process between visual artist Russell Frampton and choreographer and somatic movement practitioner Ruth Way. The article will provide an analysis of the creative processes and insights, which informed Blind Torrent. Anthropological and phenomenological theory will be drawn upon with the aim to reveal how the construction of ‘filmic ritual landscapes’ unearthed connections between site, artifact, temporality and embodied choreographic response. Connections between this screendance practice and the genres of land art and site-specific art will be discussed and inform the contextual analysis. The article will principally examine how the creation of empathic movement responses to the landscape developed a phenomenological interface between the body and landscape to enhance the proximate senses in the construction of Blind Torrent.

Keywords: imagined archaeology, landscape, proximate senses, somatic movement, ritual

This article will present a detailed contextual analysis of the creative processes and insights, which informed the screendance project Blind Torrent.1 Blind Torrent is the result of an ongoing collaborative and interdisciplinary film making process between visual artist Russell Frampton and choreographer and somatic movement practitioner Ruth Way. In this co-authored article, the analysis of the film is presented jointly in respect of this collaboration and where appropriate, will provide specific information and personal insight from our disciplinary perspectives.

Prior to reading this article, Blind Torrent can be viewed here:

The analysis explores how the construction of 'filmic ritual landscapes' unearthed connections between site, artifact, temporality and embodied choreographic response. It discusses how these connections served to realize the sensorial potential in digitally layered and scenographically enhanced interior and exterior landscapes. In reference to our disciplinary perspectives and collaboration, the article examines the creation of empathic movement responses to the landscape and the development of a phenomenological interface between the body and landscape to enhance the proximate senses. We use the term 'proximate' to refer to the haptic, aural, visual and olfactory senses and in the film where the body is in a process of transformation as it absorbs the qualities, sounds and textures in these landscapes. We draw on anthropological and phenomenological theory to both critically frame and investigate our artistic intention in the making of Blind Torrent to "return perception to the fullness of its encounter with its environment."2 This conceptual framework aims to offer an intimate perceptual lens and a means to remain attentive to the creative processes and the connections arising between imagination, somatic memory and the perceptual senses within our screendance practice.

Blind Torrent engages in processes of unfolding and forming, where intention is constantly being redefined and where, "the relationship between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed,"3 is kept alive. Similarly our analysis does not attempt to prove or substantiate findings but rather concerns itself with developing a critical praxis, one which provided us with an imaginative and analytical mode of operation to search for and 'unearth' the connections between landscape, body and constructed artifacts. We propose that this method of searching represents our practical research, and those creative processes that lead to, and uncover, a critical and analytical framework and inform our creative decision-making.

As practical scholars we move between the intuitive development of the work and our position as reflexive practitioners, critically engaging with potential new directions, insights and ideas. We describe our creative process as open, fluid and non-premeditated and propose that this enables the work to retain a focus on immediacy. Rather than employing preparatory story boarding and set choreographic sequences, intuitive artistic responses take precedence over more logical and pre-determined processes. In this writing we discuss the main thematic territories explored in Blind Torrent, and how these themes informed the construction of what we describe as an 'imagined archaeology' and its associated visual environments.

Blind Torrent (2011). Courtesy of Russell Frampton

Blind Torrent is a screendance film, distilled from over 20 hours of filming, shot on location in the agricultural hillsides of Mid Devon and in the studio at Plymouth University. Filming took place from March 2011 – January 2012, to capture the landscape in different seasonal states. The title Blind Torrent refers to the unstoppable surge of a torrent, a torrent of information, an overflowing, flooding force, but a force that has no fixed outcome or destination. The concept of the torrent in this dance film acts as a metaphor for the evolution of both human consciousness and the increasing degrees of social and cultural complexity.

Our conceptual locus underpinning the thematic content is in close alignment with performance theorists André Lepecki's and Sally Banes's proposal, "that performance practices become privileged means to investigate processes where history and body create unsuspected sensorial-perceptual realms, alternative modes for life to be lived."4 We share their argument for a "performative power of the senses,"5 in both the generation of our film material and the crafting of the final edit. Engaging with phenomenological studies and specifically leading phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty's consideration of the reciprocal relationship between the body and the world,6 one of the key philosophical imperatives was to challenge the idea of a fixed perceptual field and to focus on the body as a fluid organism, which has the potential to remain open to change and acknowledge the intelligence of the body and its systems. Central to our creative concerns was dance scholar Sondra Fraleigh's observation that somatic movement is interpreted by perceptual phenomena and that "perception does not refer to sight alone, but to all the senses."7 Working with this principle, the performers demonstrated self-awareness and a form of relational seeing, a term referred to by dance artist and educator Alison East as "sensory seeing" which she proposes that "there is another way of seeing into things, a sense of seeing that occurs at a deeply cellular level…that comes from deep in our "subterranean" consciousness and facilitates a merging with place or object."8 A state of 'awakening,’ referenced in the film draws the viewer's attention to the somatic and cultural reverberations occurring in the relationship between the body and landscape. Blind Torrent attempts to evoke a reminder of the capacity of our bodies have to be in a closer relationship with landscape through engaging the proximate senses.

Unfolding Textualities and Thematic Territories

As screendance practitioners we are conscious of being at the intersection of a complex series of multiple narratives, temporalities and trajectories. How we apply perception to unlock these creative possibilities shapes our practice. This reservoir of potential lies at the core of our creative activity and provides a conduit to access past histories and mythologies. One of the initial generative ideas for the film explored issues concerning the volume of information available today. The prevalence of this predominately internet based repository, and our relationship with ways of accessing and processing its content, differs fundamentally from an embodied, practical form of knowledge, one learnt through direct bodily experience. Dance researcher Anna Pakes draws our attention to Aristotle's reference to practical wisdom, and how this knowledge is "associated with the domain of praxis ... the moral domain in which, as human beings, we try to live and act in ways beneficial to ourselves and the social group."9

A formative anthropological imperative of most societies is the construction of a collective mythology. Social anthropologist James Frazer's The Golden Bough (1993) provides a compendium of research and description of the global and historical nature of this phenomena. The purpose of this mythological worldview is to create a context where individuals can experience a world with edges, or mutually verifiable parameters. This form of communal, often religious belief system is based on the transmission of knowledge and ancestral worship, and as Frazer describes, is specifically linked to the development of agrarian communities. Creation myths and the pantheon of deities, representative of human traits and natural phenomena serve to mythologize knowledge and to encode archetypes that have practical and spiritual relevance. The codified framework of mythology, physical terrain, flora and fauna, seasonal cycles and astronomy, served to create a sensorium of perception. The recent field of sensory ecology10 seeks to understand the interpretative processes that evolve from a proximal ecological environment; that being the immediate physical space an organism has direct contact with and experience of. Crucially this field of study provides an understanding of affordances between objects encountered in the environment and the actions they perform. In the making of Blind Torrent the affordances between props, locations and performers are explored through processes of imagination, intuition and the kinesthetic proprioceptive sense of movement.

One strategy that pre-historic cultures applied to manifest and nurture this sensorium of perception was the construction and enactment of ritual. Ritualistic activity can be seen as a way to gain a beneficial degree of control over the external forces impacting on the survival of an individual or community. Some rituals seek to link those enacting them to a deity, who represents the personified form of a specific series of traits, characteristics or perceived governance over aspects of that society. This process of a culture distilling attributes into iconic representations is closely tied to Jungian theories of the archetype. An archetype is a primitive mental image or construct, often inherited from very early human populations, that Jung postulates is present in the collective human unconscious. Jung specifically states that the notion of 'archetypes' refers to, "archaic or primordial types, that is with universal images that have existed since the remotest times."11 This idea was key to the development of central characters or personas within Blind Torrent, such as the 'corn mother' and the 'white girl' or 'acolyte,' and offered not an explanation or clarification of their specific role or reason to be, but rather an iconographic "intimation of meaningfulness."12 These atavistic reversions were sought out and used to form the core of the visual imagery, where they present forms of polarity and an implied hierarchical order. Examples include the division between underground/ground, chromatic opposites of black and white and master/acolyte, mother/daughter relationships. Throughout the construction of Blind Torrent the creative potential of the socio-historic lineage of the landscape was explored through our direct experience and knowledge of the proximal landscape where the film was located. We sought to re-imagine the rhythms of a range of localized human activities, such as work and play, and specifically agricultural labor. This allowed us to reconfigure a form of ritualized response to these locations through the medium of screendance. In Blind Torrent our personal connection with the landscape of Mid Devon provided a formative base of familiarity, where the experience of markers and signifiers of a place build up over many years of deep scrutiny, casual play, and genuine co-existence. As Pearson and Shanks discuss in Theatre and Archeology, "The square mile, the intimate landscape of one's childhood, the patch of ground we know in a detail we can never know again."13 Thus it was the primal understanding of an immediate landscape, which provided the foundation for the film.

Development of An Imagined Archaeology

As a visual artist Frampton approaches film with an emphasis on color, texture and composition, and through the development of props or three-dimensional sculptural forms. Many of the structures used in the film were developed from studio based manipulation of materials, which themselves were informed by the aura of ancient artifacts. His recent work has explored processes of stratification and deposition, which mimic the process of layering the complex surface of a painting. Frampton includes frequent references to historical presence within the contemporary landscape, encoded in personalized pictograms and encryptions within the paintings. This process has informed the development of an 'imagined archaeology' within the film. As philosopher Mark Johnson points out, "without imagination, nothing in the world could be meaningful. Without imagination, we could never make sense of our experience".14 Artifacts were made in the categories of costume, scenography and held objects, all of which sought to combine surface qualities such as patina, texture and coloring, and the minute detailing of surface pattern. In a sense there is a direct connection to the landscape itself, as structures are often made from localized materials and found objects. These artifacts served to create forms whose physical properties were shaped by the land and mediated through the artist, examples being the ritual posts and the collar [see second and fourth images].

The collar, costume, Blind Torrent (2011). Courtesy of Russell Frampton

When these artifacts were constructed, the creative aesthetic informing their appearance was painterly, but also tried to invest qualities of a regressive nature to give these artifacts a sense of their archaeo-ritualistic functionality. It is this functionality that gave these reconfigured artifacts the potential for generating movement responses. Central to this proposition of an 'imagined archaeology,' was an awareness that the vast majority of the socio-historical presence within the landscape took place prior to the development of written records. These histories are real, though un-documented, forming a speculative continuum of human ceremonial response from rites to ritual, which encompasses the cultural articulation of awareness of sentience and existence.

There are clear connections between this screendance practice and the genres of land art and site-specific art. External locations were meticulously surveyed and historically researched by the film-makers. Anecdote and localized knowledge informed central components of the final work, this understanding was gained from conversations with farm workers discussing specific geographical peculiarities and weather conditions. Land artist Robert Smithson's comparable approach to the historiographical development of Spiral Jetty (1970) Great Salt Lake, Utah USA, through discussions with locals of the lore of the region, fostered the creation of multiple, almost serendipitous overtones of meaning. Roberts elaborates on this idea stating, "Historical details refuse to remain bound to a limited, nominalist register. They have a fantastical or eerily coincidental aspect about them that suggests their connections to other scales and resonances of meaning."15 These are the details that impart uniqueness of site and profound complexity to how Spiral Jetty is experienced. Within the context of Blind Torrent we incorporated these historical details into the work through our specific knowledge of people and place and through research into the local historical land usage and agricultural practices.

The Visual Environments of Blind Torrent: The Seasons

The primary locations of the film are subdivided into four areas, each representative of a season. This alludes to repetitive natural cycles, and is a layer within the film that orders implied ritual activity and creates a distinctive cosmological structuring. The first environment created for the film was the 'sanctuary of bones,’ representative of winter, a time of reflecting, taking stock and of preparation. The recurrent transitions into this space mark a descent from sky, to horizon and to land, where a slow descent into the 'underground' represents a sinking, a dropping down into an abyss. Victor Turner's explanation of the terms 'byss' and 'abyss' has pertinence in our attempt to describe the qualities residing in this environment, "Ritual, in other words, is not only complex and many-layered; it has an abyss in it."16 Turner describes 'byss' as being deep and 'abyss' as beyond all depth and writes, "Many definitions of ritual contain the notion of depth, but few of infinite depth."

The sanctuary of bones. Blind Torrent (2011). Courtesy of Russell Frampton

The scenography for this section involved the suspension of inverted lengths of forked branches, bleached white, each possessing distinctive 'bone-like' characteristics. At staged intervals these suspended forms were set in motion and allowed to slowly revolve. The implied significance of this scenography was threefold. First to represent a repository of ancestral mythic knowledge and identity, imparting a sense of belonging and continuity. Second as a visual metaphor, the suspended branches reaching to the ground corresponding to the strength in the hands and the fingers searching to feel, to have connection, to reunite. Finally the branches as bones, suggesting the remains of generations stripped back to their core physical structure. It also referred to an internal state, a psychological space, a vestigial memory buried on the far edges of our humanity. The dancers in this environment worked with a growing awareness of just how 'alive' our bones are, and how energy is directed through our skeletal form to create and direct movement. These 'bones' inhabiting the space were an attempt to remind us of our ancient core, and of their capacity to endure and reveal an intuitive physical awareness.

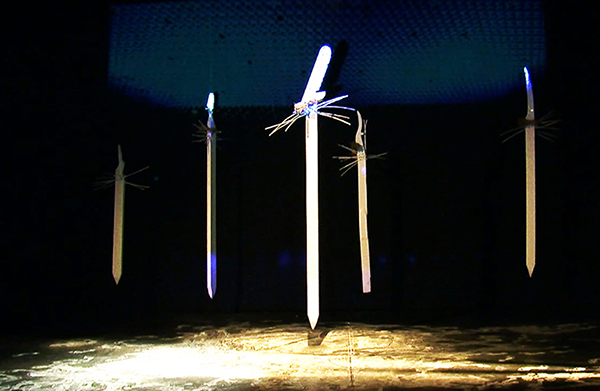

The external scenography of the five white post structures was in stark juxtaposition to the branch-filled, darkened interior spaces. These carved and painted forms were developed as sculptural responses to the demarcated post-holes on diagrammatic drawings of archeological sites, which paradoxically signify both location and absence. The subsequent re-imagining of sculpted posts to fill these spaces led to the development of a series of related structures that possess both stylistic commonality and a form of personified individuality. The constructional lineage of these posts drew from ethnic totem structures, the slender white painted series of wooden carvings produced by artist Louise Bourgeois17 and weathered anthropomorphic beach posts found in North West Brittany.

The white posts. Blind Torrent (2011). Courtesy of Russell Frampton

The posts incorporated materials from the actual sites, found objects, twigs and branches, and were arranged across a hillside to form a structure, transforming the physical space, and by implication serving to ritualize the landscape. This process of demarcation created the spatial framework of the film and much of the potential for performative action; the posts provided nodes to punctuate the filmic and actual landscape. The filming of the post sequences took place in early May and their location on verdant grassland, teeming with insect life firmly placed this environment in spring.

During summer, the ripening cornfields of Mid Devon are striking. Their glowing golden presence, combined with their inherent structural and spatial aesthetic provided a compelling filmic environment. Corn mythology permeates the world's earliest religions and belief systems, linking agriculture, growth, fertility, rebirth and the seasons in complex ritualized interrelationships.18 Cornfields are managed landscapes and within them resides a sense of collective security, an investment in the future. They are areas of provision, which tie communities together through common effort, and are places that exclude the unmanageable, the wild and the unproductive.

The decision to use this evocative and symbolically rich space led to the development of two distinct movement sequences, the 'ritual walk' and the 'transference,’ both choreographic responses to the physically limiting, localized terrain of the cornfields. The 'ritual walk' sequence deals with the processional aspect of ritualization, and is symbolic of the process of learning, of following and of the rote aspect of remembering. The 'transference' sequence involves the two figures digitally mirrored and superimposed, as if to merge their identities and embodied histories. Paradoxically this device also places the emphasis on the performers' individualities, as the contours of their faces, ages, expressions and distinct ways of performing the actions are amplified. This sequence visually articulates the notion of an exchange of cultural knowledge and empathic understanding of the continuum of lives lived.

The toil section in Blind Torrent illustrates the repetitive actions required to work the land, and symbolized the preparation of the land for sowing. Movement improvisation in this environment with a range of agricultural tools, informed a series of repetitive actions, which rhythmically scored the land, with a forceful, almost compulsive work ethic. The use of split screens and out of sync looping emphasizes the extended temporality of the agricultural work cycles. The use of poly vision, split screen editing techniques created temporal and spatial juxtapositions, which elicited a more direct apprehension of the material. Specifically the audio of the edging tool, which in one section moves progressively towards the viewer with increased amplitude on one half of the screen. This is in direct opposition to the second screen where the live audio is minimized, creating a choreographically spatial and rhythmic counterpoint through the expressive use of the tool. The creation of these dual sections enhanced the potential for formal compositional elements to be explored, and served to reinforce the recurrent visual motif within the film of the inter-relationship between the two female characters.. The implied ambiguity of distinctive identity was reinforced by similar attire and appearance, which offered multiple interpretations, such as mother/daughter, older self/younger self, master/acolyte. Stylistically the use of this technique references Andy Warhol's art house film, Chelsea Girls (1966) a film that also lacks a formal narrative structure and through juxtaposed clips builds a compelling and disjointed sensorial experience. A second major influence on this sequence was Alexander Dovzhenko's epic film Earth (1930), a silent masterpiece of early Soviet revolutionary cinema. This film idealized aspects of Stalin's program of industrial collectivism and features poetic sequences of work on the land in the Ukraine, referencing the cyclical nature of agriculturalism, and the nobility of the worker.

The work/toil section, Blind Torrent (2011). Courtesy of Russell Frampton

Somatic Memory and the Impact of Stillness

We recall formative memories; how as children, through a process of unfettered play within environments such as cornfields, the sheer joy of lying in the corn looking at the sky was experienced, providing a feeling of being protected and 'wrapped' in the land. This childlike apprehension is receptive to the proximate sensorium experienced in this landscape, imprinting a fundamental initial response, a somatic memory. A memory formed by its embodied schema and awakening perceptional phenomena, such as how the body experienced the texture and smell of the corn. This form of somatic memory surfaces within the film when a performer is seen lying in the cornfield. These filmic images represented a sleeping state or meditative repose, and a process of entering into an altered state of consciousness; the hollow created in the corn representing a portal linking the levels of sky, earth and underground.

Standing still in this landscape with an awareness of breath and alignment, Way recalls how her attention shifted from being quite passive to actively engaging all of her senses. This shift enabled a heightened receptivity to the qualities residing in the land and her place within it, and can be described as a somatic mode of attention. It facilitated a slowing and opening of her perceptual field, allowing the choreographic and movement responses to become receptive to these meditative and transformational states. Linda Hartley, a dance movement therapist offers further insight about this relationship when she writes, "today we are beginning to recognize again what ancient cultures have always known – that altered states of consciousness are vital for individual and collective health, and are fundamental to spiritual experience."19

In ongoing conversation with our performers, there is an increased awareness acknowledged, of developing strategies to avoid always feeling compelled to include kinetic representation in their performance and in the choreographic edit. Including strategies such as improvisational movement scores, working with visual imagery and stillness, assisted in the interruption of automatic and habitual movement responses. André Lepecki in his book Exhausting Dance (2006) draws our attention to German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk's premise that modernity's ontology is a pure "being-toward-movement"20 and informs the analysis of this film. Lepecki writes, "the mode of performance that occasions the self-enclosure of subjectivity within representation as an entrapment in spectacular compulsive mobility is the one that early modernity invents and gives a proper name: choreography."21 These moments of 'standing still' in Blind Torrent, where the performers stand in front of the posts strive to claim a different mode of being from "being-toward-movement."22 The performers deliberately stand outside of this form of representation in order to be in relationship to their environment through a different ontological grounding. These bodies in this landscape remain defiant through their sentient presence as women who can stand 'to be' and thus avoid representation of the body "as a sign to be consumed by the audience as a representation of flexibility, mobility, youth, athleticism, strength and economic power."23 Movement material generated by sensing and feeling the other in close proximity and apart achieved a strong mutuality between the performers. This more intimate dialogue developed an empathic movement relationship between the dancers and their environment. There was no requirement, cause or need for any representation of virtuosic acts in this work.

Walking the Land

As the performers walk through the cornfield with a repetitive and ritualized gestural sequence, it appears as if they are attempting to assert their presence and call us to attention. Hand gestures chart the space through a pattern of spatial punctuation points as if they are mapping out this experience of walking, observing and sensing in the landscape. Walking has its own rhythm, its own pace and tempo and it is this repetitive reinforcement that informs the ritualized cornfield sequences. Contemporary performance theorist Deirdre Heddon, who writes about relationships between performance and environments, refers to the art of walking. She draws our attention to phenomenologist Edmund Husserl's theories and states:

the body is always, no matter where we are, 'here', present; moving through place, our body nevertheless, serves as an anchor ... this phenomenological quality of walking is one that stressed: we 'know' the world through our physical, bodily experience of it and our literal contact of body and environment is thought to provide a privileged mode of knowledge.24

Walking through a landscape, experiencing it from the shifting perspective of motion and the direct physical contact of the body with the land forged an empathic relationship, which informed the search for a kinesthetic understanding of place and the subsequent creation of these embodied movement responses. Mike Pearson, who has written extensively on site-specific performance proposes that "walking is then a spatial acting out, a kind of narrative, and the paths and places direct the choreography."25 Walking can fulfill many functions, we walk to search for an answer, to process ideas and mull things over, we walk to empty ourselves and just reconnect with the world on an instinctual level. Our experience of landscape as we pass through it is one of constant shifting, horizons change imperceptibly, the immediate landscape moving past us, turning from sharp focus to peripheral vision, a liminal zone where the fleeting glimpse is caught from the corner of our eye.

When walking we experience an implicit duality, with both an inner dialogue and an external awareness of the spatial flux of the environment. The subtle gradients of the path, the texture and firmness of the ground beneath our feet, the curvature of the hills, the sun and wind on our face; all these sensations connect us directly to the place we have evolved to inhabit.

The Proximal Landscape

Within the disciplines of landscape painting and somatic movement practice, great attention is focused on the closest of observations of the subtle forms, colors, and textures and movement occurring in the natural environment. This artistic sensibility creates an indelible network of the meaning of a place, in much the same way a proximal landscape is imprinted on the receptive spatial and sensorial receptors of a child. The idea that both performance and archeological sites constitute sensoria, and that they are "apprehended as a complex manifold of simultaneous impressions of which any account will be inevitably embodied, subjective and poetic,"26 underpins our working methodologies. Intuitive movement responses and the nature of the physical terrain allowed ritualized, gestural sequences to evolve, which developed a specific affinity to location, creating charged liminal spaces. All these elements within the film are tautly interrelated and exist to communicate a vision of our perceptual experience. This process was applied to distill meaning, which can paradoxically be seen as both indeterminate but also possessing meaningfulness. Philosopher Max Van Manen writes, "It is important to remember that the phenomenological determination of meaning is itself always indeterminate, always tentative, always incomplete, always inclined to question assumptions by returning again and again to lived experience itself."27

A central concept within our screendance practice is a creative awareness of multiple temporalities, the use of which allow the work to enter a form of liminal space of past, present and future. Blind Torrent displays a sense of convoluted temporality, one that is, "neither a linear or a slice through time; it is convoluted. Memories, pasts, continuities, present aspirations and designs are assembled and recontextualized in a work that is both performance and archaeology."28 Merleau-Ponty implies that there is,

a relationship, between beings who are both embodied and limited and an enigmatic world of which we catch a glimpse, but only ever from points of view that hide as much as they reveal.29

Within the film we strive to create these glimpses by being attentive to the historical and sensorial potential located at the very edges of actual anthropology, entering into a liminal space of imagined ritual and artifacts.

We imagine that Blind Torrent creates an environment where "history is experienced as contemporaneous, where the past still operates on the present"30 and where the landscape becomes a palimpsest, marked, named and overwritten by the actions of ancestors. The landscape in this context can be seen as the same original document but layered with the barely discernible traces of past lives and cultures, and acting as prompts to unearth and re-imagine. During the filming process this framework allowed for new work and new understandings to surface as we began to sense the rhythm of these actions and the journeys taken within these landscapes. In Deidre Sklar's chapter "Unearthing Kinesthesia: Groping Among Cross-Cultural Modes of the Senses in Performance" (2007), she draws our attention to how people think in different representational systems and how an individual will "rely on one sensory modality to 'go after' information (visually searching, aurally questioning, kinesthetically groping)."31 Sklar's insight describes how we applied these different modalities in our interaction with the landscape. We also draw on Sklar's proposal that, "not reason but imagination is the essential meaning making operation,"32 and Johnson's argument that imagination, "works not merely reproductively to duplicate or reflect experience but productively, as an ongoing activity that structures experience by organizing perceptions, figuratively, into patterns."33

Both Johnson and Sklar's insights have significance in relation to how this creative practice functioned during the making of Blind Torrent and how our 'imagining' in these landscapes was therefore inevitably inter-subjective. Anthropologist Thomas Csordas states, "to attend to a bodily sensation is not to attend to the body as an isolated object, but to attend to the body's situation in the world."34 Through the various ways of seeing, thinking, embodying, visualizing, and generating artifacts and performance we drew on these different modalities to search for strands of information we would describe as sensed cultural knowledge.

The final 'torrent' sequence was composed of a series of rapidly flashing single frame edits of stills from the film, featuring the props, material and footage, both used and unused in the final edit. This filmic condensation offered glimpses of a hidden lineage of embodied historical experience, where artifacts, enacted ritual and ritualized landscapes become compressed into a stream of filmic images, images that can be accessed subliminally. It allows the viewer the opportunity to experience not only the implied meaning of the work, but also the work's construction, the out takes, the unused locations, its stages of experimentation and choreographic processes. This is actually the film's embodied history and intrinsically links the process of making with the film's resolution.

The multiplicity of perceptual and sensorial strands within the work, the absence of a linear narrative and the fusion of ritualized movement and archetypal references within the landscape, led to the creation of a pluralistic reality in the film. This reality sought to re-imagine potentialities existing in the creative relationship between the performers and the landscape. John Wylie, who draws our attention to phenomenological approaches to develop understanding of the relationships between people and land, culture and nature writes in Landscape (2007), "Body and environment fold into and co-construct each other through a series of practices and relations."35 The Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky expands on this idea by proposing that film, "is an emotional reality, and that is how the audience receives it – as a second reality."36 Tarkovsky further holds the belief that film is, "among the immediate art forms since they need no mediating language, cinema allows for an utterly direct, emotional, sensuous perception of the work."37 This sentiment grounds our creative methods and aims, and reminds us that our methods of searching and articulating these research insights necessitates a fluid exchange between critical thinking and practical, embodied understanding.

Biographies

Ruth Way is Associate Head of School for Performing Arts at Plymouth University and Subject Head for the Theatre and Performance Department. She is Programme Leader for BA (Hons) Dance Theatre and ResM Dance. Specialist teaching and research areas are in screendance, performance training and somatic movement practice. Ruth has performed with Earthfall and Lusty Juventus Physical Theatre and has presented her practice as research through articles, screenings and performances internationally. She is co-director of Enclave Productions with visual artist Russell Frampton and their dance films have been selected for major festivals in Europe, Australia and USA. Ruth is a registered somatic movement educator, her chapter “Somatic Awakenings” was published in Sondra Fraleigh’s book Moving Consciously (2015). Ruth acts regularly as a mentor for emerging dance artists and is a member of the board of Directors for Plymouth Dance.

Email:

Russell Frampton is a visual artist and film-maker. He is a lecturer in painting at Plymouth College of Art and associate lecturer at Plymouth University, teaching screendance and digital dance practices. Russell is an established visual artist exhibiting his paintings internationally and is represented by Store Street Gallery and Highgate Contemporary Art London, Bell Fine Art, Winchester and Smelik & Stokking The Hague, Netherlands. In 2004 he formed ‘Enclave Productions’ with Ruth Way, dance artist and choreographer to extend his work into the arena of multimedia, film and collaborative practice. His dance films have been screened at major festivals in Australia, Europe and USA and he has presented his research through international screenings, conference papers and published articles. He has devised both film and digital scenography for dance artists and theatre companies and regularly composes sound scores for film.

Email:

References

Banes, Sally and André Lepecki. "Introduction: the performance of the senses". Eds. Sally Banes and André Lepecki. The Senses in Performance. New York; Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2007.

Blind Torrent (2012). Dir. Russell Frampton and Ruth Way. Plymouth, 2012. DVD.

Bourgeois, Louise. Personages Series. Carved wood. London: Tate Modern, 2007.

Chelsea Girls (1966). Dir. Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey. Rome: Mustang/RaroVideo, 2004. DVD.

Csordas, Tom. "Somatic Modes of Attention." Cultural Anthropology 8.4 (1993): 135-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/can.1993.8.2.02a00010

Earth (1930). Dir. Alexander Dovzhenko. New York City: Kino International Corporation, 1991. DVD.

Freeman, John. Blood Sweat & Theory. UK: Libri Publishing, 2010.

East, Alison. "Performing Body in Nature." Moving Consciously Somatic Transformations Through Dance, Yoga, and Touch. Ed. Sondra Fraleigh. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015. 164-179.

Fraleigh, Sondra. Dancing Identity: Metaphysics in Motion. Pittsburgh PA: University of Pittsburg Press, 2004.

____. "Prologue on Somatic Contexts." Moving Consciously Somatic Transformations Through Dance, Yoga, and Touch. Ed. Sondra Fraleigh. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015. xxi-xxii.

Frazer, James. The Golden Bough. Ware, Hartfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1993.

Garner Jr., Stanton B. Bodied Spaces: Phenomenology and Performance in Contemporary Drama, New York: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Hartley, Linda. Somatic Psychology Body, Mind and Meaning, London: Whurr, 2004.

Heddon, Deirdre. Autobiography and Performance, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Johnson, Mark. The Body in Mind, The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Jung, Carl Gustav. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Princetown, N.J.: Princetown University Press, 2nd ed. 1968.

Lepecki, André. Exhausting Dance, New York: Routledge, 2006.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Colin Smith. London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

____. The World of Perception. Trans. Oliver Davis. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2004.

Pakes, Anna. "Knowing Through Dance Making." Contemporary Choreography A Critical Reader. Eds. Jo Butterworth and Liesbeth Wildschut. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2009. 10-22.

Pearson, Mike. Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Pearson, Mike and Michael Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology: Disciplinary Dialogues, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2001.

Roberts, Jennifer. (2004), "The Taste of Time: Salt and Spiral Jetty,” Robert Smithson. Eds. Eugenie Tsai with Cornelia Butler. Museum of Contemporary Art, Berkley: University of California Press, 2004. 97-103.

Siegmund, Gerald. "Strategies of Avoidance: Dance in the Age of the Mass Culture of the Body." Performance Research 8.2 (2003): 82 – 90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2003.10871931

Sklar, Deidre. "Unearthing Kinesthesia: Groping Among Cross-Cultural Modes of the Senses in Performance." The Senses in Performance. Eds. Sally Banes and André Lepecki. New York and Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2007. 38-46.

Tarkovsky, Andrei. Sculpting in Time. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Turner, Victor. From Ritual To Theatre: The Humans Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications, 1982.

Van Manen, Max. "The Eidetic Reduction: Edios." Phenomenology Online. Posted 2011. http://www.phenomenologyonline.com/inquiry/methodology/reductio/eidetic-reduction/

Wylie, John. Landscape, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2007.

Notes

Dance film Blind Torrent (2012) directed and produced by Russell Frampton and Ruth Way explores the rural landscape of Devon from the perspective of an imagined archaeology and ritualized movement, performers Catarina Lau and Ruth Way.↩

Stanton Garner, Bodied Spaces, 2.↩

Marcel Duchamp, in Freeman, Blood Sweat & Theory, 180.↩

Sally Banes and André Lepecki, The Senses in Performance, 1.↩

Idem., 3.↩

In Phenomenology and Perception, 239, Merleau-Ponty writes, "by thus remaking contact with the body and with the world, we shall also rediscover ourself, since, perceiving as we do with our body, the body is a natural self and, as it were, the subject of perception."↩

Sondra Fraleigh, Moving Consciously, xxi-xxii.↩

Alison East, "Performing Body as Nature," 171. East, a contributor to Fraleigh's book Moving Consciously, talks about her growing awareness of a relationship to the world beyond herself.↩

Anna Pakes, "Knowing Through Dance-Making," 18. Pakes discusses the philosophical implications of choreography as practice as research to consider practical knowledge as being distinct from theoretical understanding. Pakes refers to Aristotle's mode of practical knowledge phronesis, to highlight how phronesis referred to as practical wisdom has the ability to be sensitive and attuned to the particularities of different situations and experiences.↩

Sensory ecology is a recent field of study that investigates how organisms acquire process and use information gained from their environment, specifically how sense organs capture this information and how the significance of this information is processed to make decisions.↩

Carl Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 4-5.↩

Max Van Manen, Phenomenology Online. Van Manen refers to eidetic reduction, which differs from concept analysis by offering iconic images of phenomenon, paradoxically opening up ambiguity and indeterminacy.↩

Mike Pearson and Michel Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology, 54.↩

Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind, ix. Mark Johnson developed a theory of image schema, maintaining that image schema, are regularly embodied patterns of experience. His research in the role of bodily schema in cognition and language proposes how aesthetic aspects of experience structure every aspect of our experience and understanding.↩

Jennifer Roberts, "The Taste of Time: Salt and Spiral Jetty,” 97.↩

Victor Turner, From Ritual To Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, 82.↩

Between 1946-1955 Louise Bourgeois created a series of totem like structures, which she called "personages.”↩

James Frazer's The Golden Bough, 399-463, deals with the evolution of the corn-mother and corn-maiden and expands on the prevalence of corn mythology in primitive culture.↩

Linda Hartley, Somatic Psychology Body, Mind and Meaning, 107.↩

Lepecki's analysis of dance's political ontology draws on Sloterdijk's premise that modernity's ontology is a pure being toward movement and also his proposal that modernity's project is fundamentally kinetic. Lepecki constructs an argument that acts of stillness in choreography can stand in opposition to totalitarian political systems and ideologies. Blind Torrent explores a slower ontology to enable the performers to focus on their sentient presence and develop self-agency.↩

Lepecki, Exhausting Dance, 58.↩

Peter Sloterdijk, in Lepecki, 7.↩

Gerald Siegmund, in Lepecki, 58.↩

Heddon, Autobiography and Performance, 105.↩

Pearson, Site-Specific Performance, 95.↩

Idem., 54.↩

Van Manen, "Eidetic Reduction: edios" Van Manen's work focused on developing phenomenology as a qualitative research method and developed research models aligned to practice as research such as textual construction with the practice of writing.↩

Pearson and Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology, 55.↩

Merleau- Ponty, The World of Perception, 54.↩

Pearson and Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology: Disciplinary Dialogues, 139.↩

Sklar, "Unearthing Kinesthesia," 38.↩

Ibid.↩

Johns in Sklar, "Unearthing Kinesthesia: Groping Among Cross-Cultural Modes of the Senses in Performance," 38-39.↩

Csordas, "Somatic Modes of Attention," 138.↩

Wylie, Landscape, 144. John Wylie lectures in cultural geography, in the section 'Landscape Phenomenology' he draws on Smithson's analysis of the Spiral Jetty referring to Smithson's words and the material form of Spiral Jetty as developing phenomenological approaches to understanding landscape and describes these relations as being active, embodied and dynamic.↩

Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 176.↩

Ibid.↩