2018 NFL commercial featuring Eli Manning and Odell Beckham, Jr.

In 1987, Eddie Murphy performed a comic sketch about white men dancing that would inform future movers and makers of white male dancing in American popular culture, helping to create a trope mocking white men for their inability to dance, most often referred to as the “white man dance.” At that time, Saturday Night Live, with the help of its host Patrick Swayze, fresh off the popularity of his work in sleeper hit Dirty Dancing, contributed to the trope itself with a sketch comparing the hypermuscular physique of Swayze vs. the flabby physique of comedian Chris Farley. Almost thirty years later, American popular culture would see a return to a renewed interest in the dance film with the stripper film Magic Mike. This article argues that although Magic Mike, like Dirty Dancing, relies on the makeover trope as its narrative and thematic engine, Magic Mike revises the popular dance film format to instead focus on the relationship between two men, Mike and Adam, rather than on a heterosexual partnering. Magic Mike’s focus on this male-to-male relationship inevitably comments on the exchange between heteronormative masculinity and compulsory heterosexuality and their assumed whiteness.

Keywords: Patrick Swayze, beefcake, Richard Dyer, White Man Dance, masculinity, AIDS, screendance, film, Saturday Night Live, Chris Farley, Channing Tatum, Magic Mike, Chippendales

In Adrienne Rich's pioneering essay titled "Compulsory Heterosexuality and the Lesbian Existence," she seeks to explore the ways in which lesbian existence has been marginalized as well as the ways in which heterosexuality operates as an institution that, in many ways, has been forced onto women as a part of a heteronormative conditioning. As Rich states, "the failure to examine heterosexuality as an institution is like failing to admit that the economic system called capitalism or the caste system of racism is maintained by a variety of forces, including both physical violence and false consciousness."1 Rich's indictment of the strictures of heterosexuality as an institution of cultural conditioning in 1980s America, when the essay was published, becomes particularly cogent when exploring the popularity of dancer and film star Patrick Swayze, who became a heartthrob sensation after the unexpected dance film hit, Dirty Dancing,2 in 1987. Almost thirty years later, a new dance sensation hit theaters in the stripper film Magic Mike.3 Although Magic Mike follows a very similar narrative pattern and relies on a similar makeover trope as Dirty Dancing, Magic Mike revises the popular dance film format to instead focus on two men, Mike and Adam, rather than on the heterosexual partnering of a man and a woman. Even though Magic Mike focuses largely on the relationship between two men, the film's dance finale ends, just like Dirty Dancing, on a heterosexual pairing (between Mike and Joanna, Adam's sister), thus reinforcing a compulsory heteronormativity. However, the film's central focus on the relationship between the two men adds a slightly different thrust than that of Dirty Dancing—one which aims to speak to the provocative exchange of heteronormative masculinity and compulsory heterosexuality and the assumed whiteness of both. I argue that dancing in these films becomes the way that heteronormative masculinity and compulsory heterosexuality are made legible and understood by its audience.

In order to contextualize my argument between Dirty Dancing and Magic Mike regarding whiteness and compulsory heterosexuality, especially as intersecting with screendance in contemporary American film, I begin by discussing two contemporary American popular cultural texts that employ the iconic dance lift during Dirty Dancing's finale: an NFL commercial which parodies the lift during the recent Super Bowl LII; and a scene between Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone in the 2012 film Crazy, Stupid, Love. I will frame the ways in which both compulsory heterosexuality and whiteness are made central in these sequences, even when the NFL commercial constructs a kind of disguise of cross-racial harmony. For contextualization, I establish Eddie Murphy's "white man dance" sketch from his 1987 film Eddie Murphy Raw as the inception of a trope that began to portray (straight) white men as "bad" dancers in order to more clearly affirm these men in a position within hegemonic masculinity. These early discussions in the paper then help to further establish the ways in which I analyze Magic Mike in terms of its representations of whiteness and compulsory heterosexuality.

As I argue throughout, dancing itself is offered as the glittery excitement of these respective ideologies, but that promise of excitement and enjoyment, for the most part, is unfulfilled. Further, when compulsory heterosexuality and compulsory masculinity are set side-by-side in contemporary American cinema, it is heterosexuality which wins out, whereas with masculinity the participant seems to come up empty-handed—his investment in 'masculinity' leaves a lack. I conclude the essay with yet another example of a contemporary American popular culture text that references the lift from Dirty Dancing. I engage with the film Silver Linings Playbook, which I argue re-envisions the lift to complicate the gender and racial significations of the earlier sequences discussed throughout this article.

On the night of Super Bowl LII, February 4th, 2018, New York Giants' players Eli Manning and Odell Beckham, Jr., along with the New York Giants offensive line as the supporting dance staff enact a parody of the iconic final dance scene in Dirty Dancing. The commercial,4 a parody of the controversial touchdown dances during National Football League (NFL) games and as such, an advertisement for the NFL itself, ends with the iconic lift—Eli Manning (as Johnny Castle) literally lifts Odell Beckham Jr's (as Baby Houseman) above him.

2018 NFL commercial featuring Eli Manning and Odell Beckham, Jr.

In the film Crazy, Stupid, Love,5 the character Hannah (played by Emma Stone) decides she's going to finally make it with "the hot guy from the bar," Jacob (played by Ryan Gosling). Much to Jacob's surprise, Hannah subverts his controlled game of picking up women when she asks Jacob to tell her his "big move," the one that gets women into bed. He refuses at first, but eventually relents and confesses to Hannah that he usually "works Dirty Dancing into the conversation." Jacob proceeds to explain that he tells every woman he picks up that he can do the lift that Patrick Swayze does with Jennifer Grey at the end of the movie. He plays the song, he does the lift, and sure enough, every woman always wants to have sex with him. Jacob agrees with Hannah that it is the most ridiculous thing "ever heard," but "it works. Every time." Jacob then proceeds to do the same for Hannah. Once Hannah and Jacob do the lift, she immediately relents and asks him to take her to his bedroom.

There are many audiovisual texts which reference the iconic lift sequence from the end of Dirty Dancing.6 What is it about that Dirty Dancing lift that so thoroughly occupies an iconic space within screendance film history? I would argue that the lift is emblematic of the exchange within the institution of compulsory heterosexuality. Somehow it enacts how women identified bodies can give into male identified bodies and be hoisted up and supported assuredly. In the final lift scene of Dirty Dancing, Baby gives a slight nod of consent to Johnny after he finishes a short ensemble dance routine on the floor. She stands on stage watching the audience in their seats below while Johnny and the staff at Kellerman's dance in unison. Once Baby has given Johnny her consent to perform the lift, a move she has been unable to perform up to this point in the film due to her lack of trust in her own body and herself, she is supported by two other male members of the dance staff as they delicately lift her from the stage onto the floor. The dance lift is the quintessential image of the heterosexual institution. This is the moment of movement-to-stillness that is legitimized by a heteronormative society—not only are Baby's father and the elitist white audience enraptured by the physical feat and their dance chemistry and execution, but the non-white dance staff has been fully integrated into the production as well. It is a cross-racial integration across class lines. The dance that leads to the lift has also integrated the taboo "dirty" dancing previously not allowed on the stage at Kellerman's. In the lift, Baby gives herself over to Johnny and Johnny delivers—and it is through Baby that Johnny also inherits the privilege and acceptance of her station.

Screenshots of Jennifer Grey (Baby) and Patrick Swayze (Johnny) in Dirty Dancing Dir. Jerry Zucker, 1987

I do not recall when I watched Dirty Dancing for the first time, but I do remember that it had a significant impact on me like no other film had. I wanted to fall in love with a man who would teach me how to dance, who would awaken my relationship to my body, sexual and otherwise. It left a deep psychic imprint on how I was to approach romantic relationships with men, and what impression I expected to leave on a significant other. However, it is not the moment of the lift from the finale that I longed to have with a dance partner like Johnny Castle—but instead it is a lift that occurs within the routine that takes place on the stage that I yearned to replicate. Johnny lifts Baby onto one side of his torso, the feminine layers of her dress swishing as he turns her, her legs forming a split in the air. It was this lift that indelibly remains in my memory as it is reflective of a more co-dependent moment, one requiring Baby to stay tethered to his body and one less in celebration of her newfound independence. A few years ago, I uncovered a journal I kept during my adolescence. I was determined to find Patrick Swayze in Hollywood when I grew up, and convince him to become my dance partner. At that point in my life (I would discover my own queerness much later), it was not a question that I would need to seek a heterosexual partnering in order to define myself, nor was it a question what gendered body, exactly, would need to be this partner for me.

I include this anecdote to speak to the power of the heterosexual institution as constructed in this iconic film, and as emblematized by the meaning inscribed in the lift. As Rich states in her essay, "[W]e may faithfully or ambivalently have obeyed the institution but our feelings – and our sensuality – have not been tamed or contained within it."7 It would be many years before I would understand Rich's poignant point about the ways in which heteronormativity conditions us to fall under the obedience and seduction of the heterosexual institution and many years to investigate the ways in which contemporary film replicates this ideology. As Rich states, and this was even truer for Baby, who meets Johnny in the mid-1960s, "[W]omen have married because it was necessary, in order to survive economically, in order to have children who would not suffer economic deprivation or social ostracism, in order to remain respectable, in order to do what was expected of women, because coming out of 'abnormal' childhoods they wanted to feel 'normal' and because heterosexual romance has been represented as the great female adventure, duty, and fulfillment."8 Dirty Dancing fulfills this compulsory heteronormativity through its use of dance and the lift sequence. It also asserts dancing as a masculine activity through the technical skill and physicality of Patrick Swayze's character. There is no doubt that Johnny Castle is anything but masculine and heterosexual despite his affinity for dance.

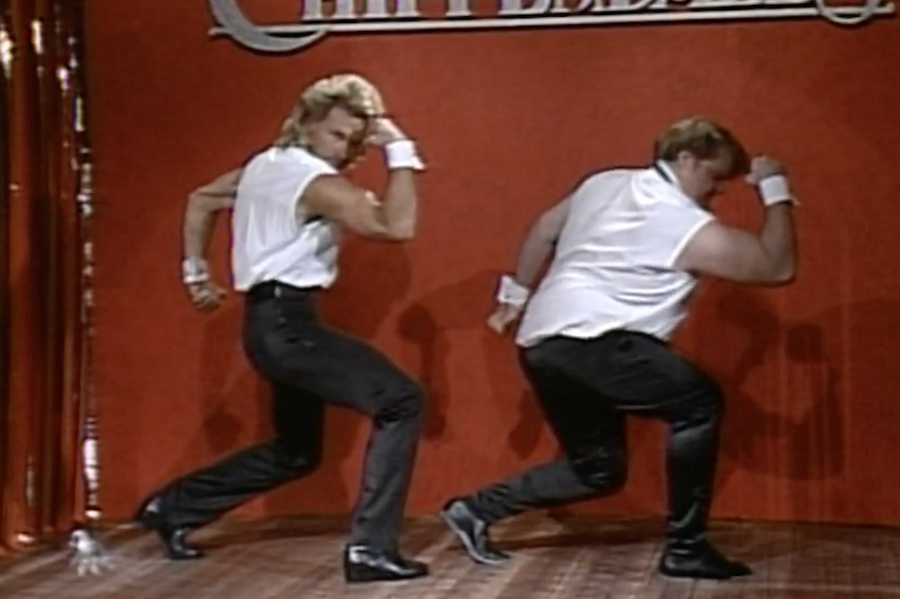

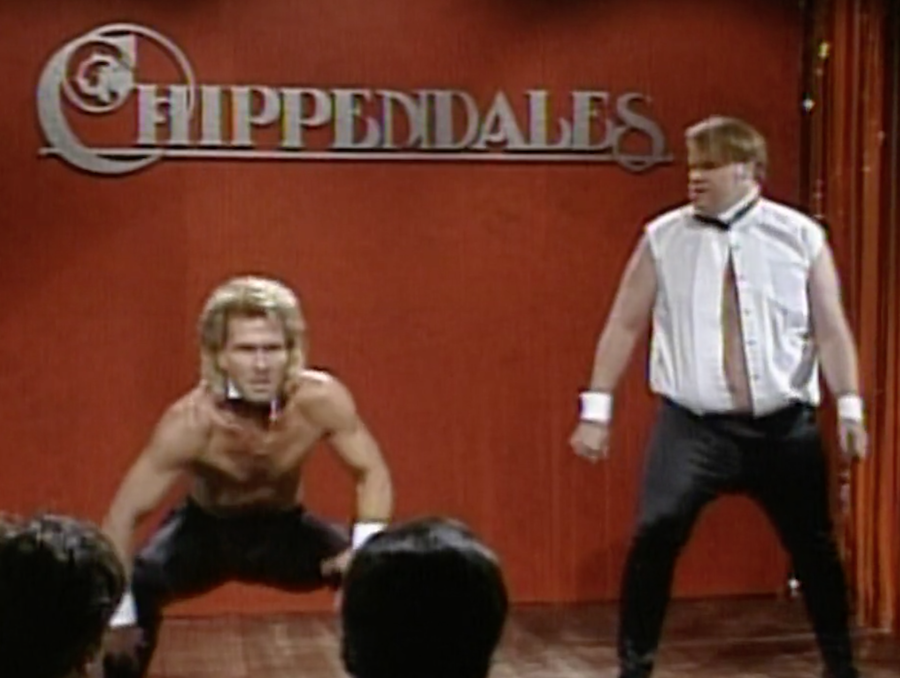

I will briefly address the ways in which dancing ability (or lack thereof) is used for comic effect particularly when paired with (straight)9 white hypermasculine men beginning in the late 1980s. In order to contextualize this trend, I will take a look at a sketch from Saturday Night Live when Patrick Swayze was the host which parodied the Chippendales male dance troupe. This sketch is also particularly useful in connecting Swayze's masculinity in Dirty Dancing to the masculinity of Channing Tatum in his role as a stripper in the film Magic Mike which I will later address.

Saturday Night Live aired the sketch titled "Chippendales Audition" on October 16, 1990. Actor and dancer Patrick Swayze hosted the episode during his peak in popularity in Hollywood, cemented after Dirty Dancing became a sensation just three years prior. This sketch parodied the hypermasculine physique Swayze was known for, an archetype that thrived on 1980s Hollywood screens, by casting Swayze as an erotic dancer auditioning for Chippendales, the first all-male stripping dance troupe known for its striptease routines and its signature costume of bow tie and shirt cuffs worn on a bare torso over black pants (coincidentally, Magic Mike employed very similar costuming as worn by Channing Tatum and the other strippers). In the sketch, a panel of judges made up of two men and one woman (played by Mike Meyers, Kevin Nealon, and Jan Hooks) are trying to decide whether to cast Patrick Swayze or Chris Farley.

The two men step on stage in identical outfits—sleeveless white tuxedo shirts tucked into black tuxedo pants, white cuffs with black cufflinks, and black bowties. Initially, the comic thrust lies in the visual/physical comparison of these two male figures: Swayze's toned muscular physique next to Farley's soft, overweight form, enhanced by the sloppiness of Farley's off-kilter bowtie. As they begin to hip thrust and fist pump their arms, the 1981 rock anthem "Working for the Weekend" by the Canadian rock band Loverboy, furthers the comic backdrop for the sketch. The two men turn their backs to the judges while they roll their shoulders back and rotate their hips in seductive circles. Swayze's orbit is tight and controlled while Farley's is loose and wide. The two men perform a half turn to face the judges in profile as they flex their biceps in a high lunge. As they turn to face full frontal again, Farley's shirt has humorously popped open. They strut downstage as Swayze strips, revealing his muscular, hairless chest, rubbing his shirt between his legs, tucking his pelvis forward and back, groping his legs, and arching his back. Farley looks over at Swayze, and removes his shirt as well, revealing again the visual comic difference in his own physique, repeating Swayze's moves with an exaggerated concentrated expression, rubbing his hands all over his hairy and flabby chest. They continue to attempt to outdo each other in this vein, gyrating, spinning, and flexing, Swayze offering the audience sex appeal, Farley his comic antithesis.

Screenshots of Patrick Swayze and Chris Farley in Saturday Night Live, Chippendales Audition sketch. Dir. Lorne Michaels, Oct. 16, 1990

The sketch ends with the judge, played by Kevin Nealon, explaining that, while the character performed by Chris Farley's dancing was "great" and his presentation "sexy," Swayze's body was "much, much better than yours. You see, it's just that, at Chippendales, our dancers have traditionally had that lean, muscular, healthy physique . . . whereas yours is, well, fat and flabby."10 As the judge continues to explain that they considered casting Farley to appease the "heavier" female audience members, Swazye's character begins to think to himself, in voiceover, as "I've Had the Time of My Life," the song famous for the Dirty Dancing finale number, plays softly in the background: "[E]ven as I stood there listening to them explain why they'd chosen me, I still couldn't believe it. . . . I never saw Barney again but I would never forget how, for one moment, he brought out the best in me. That was the time of my life."11

The sketch is significant for contributing to the rise of what I call "the white man dance trope," a trope which mocks (straight) white men's ability to dance. The more masculine the man, the worse it seemed he needed to dance in order to confirm his position within hegemonic masculinity. But, this sketch does not just represent the white man dance trope, but the space between the type of dance being seen by men in the late 70s and early 80s, in which masculine dancing men took center stage in dance film (such as that performed by Swayze in the sketch), and the rise of the white man dance trope (represented by Farley's performance as Barney), in which a man's inability to perform dancing became a thing of comedy. What this particular sketch seemed to also predict, however, was the phenomenon that was most concretized by the Magic Mike franchise, in which sexualized dancing by men, performing for the arousal of women, would become yet another thread via which an audience would accept a (straight) white man's dancing. This trend furthers my contention of the relationship between compulsory heterosexuality and dancing in contemporary American film. Because this sketch alludes to a connection between homoeroticism and the ability of white men to dance, it sets up the groundwork for my overall argument about Magic Mike. It was not only his sexuality that would be questioned in a (straight) white man who could dance, but also his place within traditional strictures of heteronormative masculinity.

The white man dance trope assumes that (straight) white men do not have the ability to dance well. I am locating the inception of this trope in American popular culture in 1987, when Eddie Murphy in his stand-up comedy film Eddie Murphy Raw, performed a sketch most frequently referred to as the "white man dance." It gained traction especially after The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air's Alfonso Ribeiro labeled it as such when exposing it as one of his influences for the dance he performed repeatedly on the show.12

In 1987, Eddie Murphy Raw was delivered to public audiences through a wide theatrical release. The film made over 50 million dollars in profit at the box office.13 The film's wide reach is significant because the film gave the American public access to a joke mocking (straight) white male bodies that would become a popular cultural phenomenon, Interestingly enough, Eddie Murphy does not explicitly call out white men. In the sketch, Murphy opens with the following: "I went to a disco recently and watched white people dance. Ya'll can't dance. I'm not being racist; it's true. Just like when white people say Black people have big lips, it's not racist; it's true. Black people have big lips, white people can't dance."14 He proceeds to mimic their movements for the audience. It is Murphy's representation of a particular choreography of unskilled danced whiteness that became ubiquitous in American popular culture for directly informing many other parodies of (straight) white men.

Screenshot of Eddie Murphy in Eddie Murphy Raw. Dir. Robert Townsend, 1987

Murphy's sketch, contextualized within a stand-up career concretized and well-versed in homophobic content, hit on an ideology already cemented within the fears of white masculinity—fears of homosexuality and effeminization. These fears were particularly potent given the rise of visible homosexual masculinity in the mainstream, which was exacerbated by the AIDS epidemic in the United States during 1980s.15 According to David L. Moody in The Complexity and Progression of Black Representation in Film and Television, which borrows from E. Patrick Johnson's Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity,

The Reagan-led conservative administration in the White House during the 1980s paved the way for the reemergence of "family values," while simultaneously marginalizing those outside the heteronormative sphere of family including gays, lesbians, single working women and single parents. ... Moreover, the insidious antigay pro-family sentiments promoted by the Reagan administration not only supported [w]hiteness as the master trope, but ironically also stimulated the career of a contentious Black comedian named Eddie Murphy. One could infer that Murphy's stand-up character during the 1980s became another minstrel cast member at center stage for the fulfillment of [w]hite political fantasies. ... Murphy had a large [w]hite constituency from the very beginning, and by adding homophobic dialogue to his repertoire, his stand-up act ultimately became commodified, and sold as amusement.16

In other words, Murphy's homophobia, particularly expressed in his jokes about his fear of gay men and contracting AIDS, became the engine through which his jokes targeting white men could be read. In Eddie Murphy Raw, which opens with a sketch discussing his fear of gay men chasing him out of anger at his anti-gay jokes in his previous television special Eddie Murphy: Delirious (1983), the white man dance sketch thus becomes burdened with an indictment on white masculinity, as contextualized by a paranoia of homosexuality. As a point of comparison, one can note the difference in his depiction of white men with his sketch featuring Italian American men, who he likens to Black men, even referring to them as N—s, and who Murphy imbues with hypermasculinity in his impersonation, complete with an arched back and crotch grab. It is telling that in Eddie Murphy's view, Italian American men, unlike white men, only visit nightclubs in order to get into physical altercations with other men, their violence and aggression symbols of their affirming masculinity, whereas white men attend nightclubs to fail at dancing, their heads facing the floor, their shoulders rolled forward, their arms swinging back and forth with snapping fingers, a familiar symbol representative of the Black homosexual drag queen.17 Murphy uses gestures that signify effeminization and homosexuality in order to criticize white men's failure at traditional notions of American masculinity. The relationship Murphy explores between (straight) white masculinity and effeminization/homosexuality become even clearer when set apart by his depiction of Italian American men, for whom he creates a hypermasculinity in stark contrast. By including in the same stand-up special a sketch of Italian men, white American men who stand in as more "ethnic" than the generic white male, the generic white male dancer then becomes further emasculated through this juxtaposition.

For better or for worse, Eddie Murphy pinpointed a very adept ideological relationship between (straight) white men's relationship to dance and their subsequent fear of being marked as homosexual or effeminate, which risked taking white men further away from their investment in masculinity. As can be seen from the plethora of resulting white male dances emerging from contemporary American popular culture after the release of Eddie Murphy Raw and his white man dance sketch, such as Pretty in Pink's Duckie, Friends' Chandler Bing, and The Office's Michael Scott, the sketch enabled white men to explore the relationship between masculinity and white men's expected inability to dance well. As white men dancing, they did not risk having their heteromasculinity being called into question. However, in turn, Murphy's sketch also cemented a one-dimensional view of the white male dancer, one that assumed white men could not dance, and those who could called into question their ability to perform hegemonic expectations of contemporary American masculinity.

Masculinities Studies scholar R. W. Connell is most widely credited with popularizing the term hegemonic masculinity in the early 1980s, which refers to "the pattern of practice (i.e., things done, not just a set of role expectations or an identity) that allowed men's dominance over women to continue."18 Connell is quick to point out that hegemonic masculinity may not be normative (i.e., performed by most men), but that it is a dominant gendered expectation. Sociology scholars who focus on white masculinity, such as Michael Kimmel, Tim Wise, and James Messerschmidt, mix theoretical concerns with qualitative research methods in order to further Connell's research by addressing how the pressures of hegemonic masculinity affected American men in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, particularly in the expectations around financial support, producing labor, maintaining an athletic and reproductive body, and effecting a stoic (or emotionally undemonstrative) exterior. Gender Studies scholar Judith Butler's contention that gender is not innate but is performed and made through reiterated patterns of gendered behavior offers another way to explore the reiterated patterns of comic dancing by (straight) white men. Finally, film scholar Laura Mulvey argues that classic Hollywood filmmaking creates a male gaze through the depiction of the woman on screen as an object of desire can provide a framework through which to explore the ways in which men on screen become the object of desire for women audiences, especially when considering the athletic physique of (straight) white men moving on screen supposedly for the sexual arousal of heterosexual female viewers, while the dancing itself is constructed in a way to appear athletic (or comical) for the satisfaction of an assumed heterosexual male audience.

The Super Bowl ad featuring the Dirty Dancing parody merges images of hegemonic masculinity with clear references to the finale dance sequence in order to fuse gender patterns of masculine behavior with the heterosexual pairing of the original. For example, the commercial begins with the imprecise and informal address of male homosociality: "Wanna work on that thing?" Manning asks while casually nudging Beckham Jr's arm with his elbow. This invitation firmly plants the commercial in the territory of masculinity so as not to portray men who represent the ultimate ideal of American masculinity—American football players in an ad on Super Bowl Sunday—as "too feminine." In this way, when the dance is integrated into the ad and performance, their hegemonic masculinity will stay intact. Their masculine coded body language and rhetoric continues when Beckham Jr. responds: "[L]et's do it," and Manning confirms, "[L]et's get it," as they both drop their face towels on the table at the sidelines of their practice field. After they perform their winning "touchdown," Beckham Jr.'s face appears in medium close up, his face sincere and stoic towards the camera as "(I've Had) The Time Of My Life" begins to play in the background. He abandons the football on the ground beside him as he whips his head (and hair) around in a feminine coded gesture so that he looks towards the camera (and Manning, not shown in the shot) while his torso still faces away from the camera and Manning. They gradually walk toward one another and they grip each other's hands and embrace. Hands still connected, they open outwards to start the Dirty Dancing dance from the finale scene, Beckham Jr.'s leg pointed in a tendu to the side. What is important about the way that the two men perform different moments from the dance sequence is that the sequence remains masculine and imprecise and it is this slippage between their performance and the audience's expected memory of the perfected sequence from the film's original that creates the comedic thrust while keeping the masculinity of the two figures intact. The dance finale is gestured at without flawless execution; it is a parody, after all. They don't perform it too well, thus arousing suspicion with regards to the homoerotic nature that could be placed upon the two men. It also does not jeopardize their position within hegemonic masculinity and its association with athletics. The ad itself advertises a new change in touchdown dances this season, in which the NFL allowed choreographed dances after teams successfully made touchdowns. This rehearsed choreography, however, remains tethered to heteronormative masculine movement language, regardless of the ability these men may have to technically execute the choreography.

The racialized pairing in the duet adds further critical fodder. This is not just any Super Bowl. This is 2018 during the Trump Administration, a particularly culturally divided moment in the United States. This is also the Super Bowl post-Kaepernick, in which the NFL was accused of blackballing 49ers quarterback, Colin Kaepernick, for protesting police violence against Black men by taking a knee during the National Anthem.19 During this Super Bowl, protesters who stood outside the Super Bowl in support of Colin Kaepernick were arrested by law enforcement. Additionally, this is also the Super Bowl in which Justin Timberlake, a (straight) white male pop star/dancer known for being influenced by Black dancers and singers such as Michael Jackson and James Brown was criticized for not doing more to defend Janet Jackson when a wardrobe malfunction during the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime Show, referred to as Nipplegate, caused Janet Jackson to be blacklisted and her career to stall while Justin Timberlake's solo career skyrocketed.20 This is also the second Super Bowl in which Patriots' quarterback Tom Brady (who helped lead his team to a Super Bowl victory during 2017 and whose team also played in the 2018 Super Bowl) was criticized for his personal friendship with President Donald Trump.

The commercial thus offers a non-threatening view of the inter-racial relationships in the NFL, one in which the white quarterback literally elevates his often Black teammates. Interesting to note in the video is that blackness is conflated with the (feminized) role of following in partner dancing since it is Beckham Jr. who follows Manning's lead and gets lifted up. It is perhaps true that on the football field, quarterback Eli Manning offers a strong "Johnny" to help support Odell Beckham, Jr's "Baby." However, given the controversy between Kaepernick, Trump, and the NFL, the NFL as a corporation and sponsor of this commercial used the iconic choreographic moment from Dirty Dancing to not only draw attention away from the controversy through a popular culture nostalgic moment, but more importantly (and perhaps even deviously) reinforced the trope that white masculinity should lead. By tying Manning to Patrick Swayze's Johnny Castle, the commercial reinforces the hypermasculine trope.

In the film Magic Mike, I argue that Mike took Adam aka "The Kid" under his wing and showed him the ropes of the stripping world. However, by the film's end, in a masculinist turnabout, the Kid goes out on his own and gets involved in dealing drugs and Mike loses his entire life savings—the savings that would free him from the confines of the hustling world of being a sexual commodity—by trying to save Adam's life. Adam loses himself to the depraved world of substance abuse. The movie hints at the empty excitement that masculinity attempts to offer to young hypermasculine (straight) white men. Off the field, "Baby" as re-imagined in Odell Beckham, Jr., cannot rely on Eli Manning's "Johnny"; Mike cannot rely on Adam, at least, not in the same way that Baby is able to rely on Johnny Castle and the masculinity he represents in the resolution of Dirty Dancing. In order to fit in a hegemonic masculinist (and capitalist) framework, the white quarterback must capitulate to the NFL and become the signifier (via the commercial) for the NFL's white hetero-patriarchal corporate power.

Important to note is that the dancing in Dirty Dancing, Magic Mike, and even Justin Timberlake's halftime show rely upon Black social and vernacular dance. As Richard Dyer states in his chapter "White Enough" in Yannis Tzioumakis and Siân Lincoln's The Time of Our Lives: Dirty Dancing and Popular Culture, "Dirty Dancing plays fast and loose with the black component of Dirty Dancing. It seems simultaneously to acknowledge it and erase it."21 Dyer further explores the ways in which blackness is acknowledged—through bodies mostly in the background, like well-known tap dancer/Vaudeville performer Honi Coles as the greatly underutilized Tito the bandleader, unnamed nonwhite dance couples in the dancing staff, music from Black artists in the 1960s, and the Jewish setting of Kellerman's indirectly referencing a long history of Jewish and Black vaudeville and blackface. Johnny and Baby, then, as the white couple the film centers on and celebrates in the final scene, are literally and figuratively held up by Black bodies—through the dance moves that they perform, the music they often perform them to, and the Black dancing bodies that surround them in an ultimate moment of integration. As argued in Broderick Chow's article "Every Little Thing He Does: Entrepreneurship and Appropriation in the Magic Mike Series," Magic Mike's dance moves performed by Channing Tatum are "based firmly in the idiom of hip hop and street dance . . ."22 Given that the blackness of Swayze and Tatum's respective dance moves becomes most evident in the movement that is meant to be sexually suggestive, the blackness then stands in as a sexual commodity, an element which lends sexuality to white bodies while commodifying its Black origins. A class dimension emerges in both films as well as both men use their sexual bodies for money: Johnny sleeps with his dance students at the resort when they give him money and jewels23 while Mike strips in order to start his own furniture business. One can see how these parallels with the Super Bowl LII and these two films appropriate blackness as a functioning commodity that can be sold to a white mainstream audience through ideas of hegemonic (white) masculinity.

Unlike the hegemonic masculinity embodied in the NFL commercial and Magic Mike, the sequence in Crazy, Stupid, Love that started this article emblematizes the fantasy-driven compulsory heterosexual enterprise in its remake of the lift scene. This is an important moment in the romantic comedy as "the hot guy from the bar," Jacob, who is a womanizer and disinterested in romantic relationships, falls in love with Hannah. What Hannah and Jacob don't know at this point, however, is that Jacob is responsible for another Dirty Dancing-like trope within the film—he has been the player remaking Hannah's father Cal and helping him rediscover his own masculinity in the middle of a separation from his wife after his wife admits to an affair.

Crazy, Stupid, Love remakes key elements with Dirty Dancing in a couple of important ways. In Dirty Dancing, Baby must rebel against patriarchy, namely her father, in order to find herself—however, she must do this by pairing herself with another male partner, Johnny, who represents her sexual awakening and entrance into womanhood as he educates her on how to dance, and make love, with a man. Homosocially, Jacob teaches Cal how to find his own manhood by teaching him the machinations of masculinity—how to dress "like a man," how to flirt "like a man," and how to pick up women. Meanwhile, Hannah lives a boring life with her lawyer boyfriend while she studies to pass the bar exam. It is Jacob that takes her out of the monotonous and sexless life and brings her into herself while she brings Jacob into a committed meaningful relationship. What is important in this film, however, is that Jacob is not just any man, but is played by the ultimate image of contemporary heterosexual masculinity: Ryan Gosling. Often compared to Gary Cooper and Marlon Brando, Gosling manages to embody masculinity while also parodying it, exposing the holes in this perfectly oiled (or so it seems), machine. As Sean Fennessey states in his article "The Two Goslings: A Movie Star Divided," the classic Gosling role is both "talking in that made-up Brooklyn newsboy accent and scoring the girl while winking at another across the room" and "a meta-commentary on being Ryan Gosling. . . . The duality of the bro."24 Hannah is legitimized by being able to score "the hot guy from the bar," but further than that, by being able to change Jacob from his player ways, just as Baby brings Johnny into her world of status and privilege as he brings her into her own sexual identity and leaves his hustler status to be with her. In a sense, in this fantasyland of heterosexual promise, everyone wins. Even in Magic Mike, the film does not end in a reconciliation of Mike and Adam, but with the consummation of Mike's relationship with Joanna, a stand in for Adam.

In the NFL commercial and Magic Mike, it is clear that the risk-reward of masculinist exchanges is spurious. Although it is further bogus when it comes to the fictional depiction of heterosexual partnerships in Crazy, Stupid, Love and Dirty Dancing, the dance is still ideologically and contextually employed in order to legitimize compulsory heterosexuality. However, as Rich contends, "in the absence of choice, women will remain dependent upon the chance or luck of particular relationships and will have no collective power to determine the meaning and place of sexuality in their lives."25 In a sense, perhaps it is yet another remake of the Dirty Dancing lift, in another contemporary re-envisioning of the dance film, which portrays a more accurate example of a heterosexual partnership in which both partners have equal agency and the dance provides an example of what that partnership truly requires.

In The Silver Linings Playbook (2012, directed by David O. Russell), misfits Pat (played by Bradley Cooper) and Tiffany (played by Jennifer Lawrence) perform in a dance competition in the climax of the film. Their dance is a metaphor not only of their relationship, but of their personality quirks as sufferers of clinical depression. The random music and quick switch in styles of dance used in their choreography exemplifies their unstable psychological states. Near the end of the dance, Tiffany moves apart from him. She runs and jumps into a lift, although not one as recognizable as that from Dirty Dancing. Pat's head gets awkwardly stuck in her crotch, her leg remains in a sloppy passé, and the audience watches in horror. It is an uncomfortable moment, but an image that does not shy away from the imperfection of masculinity as merged with heterosexual partnership.

Bradley Cooper (Pat) and Jennifer Lawrence (Tiffany) in The Silver Linings Playbook. Dir. David O. Russell, 2012

As seen throughout the film but thoughtfully rendered in this particular dance scene, these two characters accept one another as they are. The dance is uneven and filled with moments embodying "failures" as well as victories, which more closely resembles the reality for two characters suffering from and experiencing non-normative lives (and relationships) due to their psychological conditions. In this sequence as in their relationship, Pat and Tiffany struggle towards an imperfect union, one in which neither person is clearly the lead or the follower, but each are seen and able to express their own needs and inadequacies. The failure of the lift subverts the compulsive heteronormativity centered in the original lift in Dirty Dancing as well as in the NFL commercial and the scene from Crazy, Stupid, Love, offering a more complex envisioning of a partnering that also reveals the empty artifice of compulsive heteronormativity.

The (straight) white male dancers who are accepted within the larger American imaginary most often require bargaining with the currency of the hypermasculine. In other words, be it the naïveté of adolescence, the coolness of blackness, or the athletic physiognomy, (straight) mainstream Hollywood films and advertising suggests that white men who dance must be affirmed via the lens of masculinity before they are accepted as happenstance dancers within American popular culture and media. It is therefore the disciplinary framework of dance studies, which can provide a lens through which to continue to critically engage with filmic representations of hegemonic masculinities and their ideological circulations.

Addie Tsai is a scholar and writer interested in dance studies, psychoanalytic theory, creative writing, hybrid art forms, and literature of those that are marginalized, such as gender/queer literature, disability literature, and literature that addresses multiple intersections of otherness. Her poems and creative nonfiction have been previously published in journals such as NOON: A Journal of the Short Poem, American Letters and Commentary, Forklift, Ohio, The Denver Quarterly, The Collagist, The Volta and Post Road, among others. Her queer Asian young adult novel, Dear Twin, will be published by NineStar Press in August, 2018. She was co-conceiver for Dominic Walsh Dance Theater’s dance theater adaption of Victor Frankenstein, and narrative collaborator of DWDT’s production, Camille Claudel. Addie Tsai currently teaches Composition and Literature at Houston Community College, where she has coordinated a nationally-known reading series focusing on writers of color, and has taught creative writing classes on Personal Essay and Creative Nonfiction at Inprint and The Jung Center (in Houston). She received her Master of Fine Arts at Warren Wilson College in Poetry, and is currently a candidate at the Texas Woman’s University’s Ph.D. in Dance program. She is a previous contributor to The International Journal of Screendance.

Email:

Website: www.addietsai.org

Ardolino, Emile. Dirty Dancing – The Time of my Life (Final Dance) – High Quality, YouTube Video, 4:28, January 7, 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpmILPAcRQo.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Chow, Broderick. "Every Little Thing He Does: Entrepreneurship and Appropriation in Magic Mike Series," Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association 6.1 (Spring 2017): https://doi.org/10.25158/L6.1.3

Connell, R.W. "Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept." Gender & Society 19.6 (December 2005): 829-959. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

Crazy, Stupid, Love. Directed by Glenn Ficarra and John Requa. 2011. Los Angeles: Warner Brothers. DVD.

Dirty Dancing. Directed by Emile Ardolino. 1987. Santa Monica: Lionsgate. DVD.

Dyer, Richard. "White Enough." In The Time Of Our Lives: Dirty Dancing and Popular Culture. Eds. Yannis Tzioumakis and Siân Lincoln. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2013. 73-85.

Eddie Murphy Raw. Directed by Robert Townsend. 1987. Hollywood: Paramount Pictures. DVD.

Fennessey. "The Two Goslings: A Movie Star Divided," 2013, https://grantland.com/hollywood-prospectus/the-two-goslings-a-movie-star-divided/.

Magic Mike. Directed by Steven Soderbergh. 2012. Los Angeles: Warner Brothers. DVD.

Michaels, Lorne. Chippendales Audition, Video, 6:08, October 16, 1990. http://www.nbc.com/saturday-night-live/video/chippendales/3506016?snl=1.

Moody, David L. The Complexity and Progression of Black Representation in Film and Television. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017.

Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18.

Rich, Adrienne. "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence." In Feminism and Sexuality. Eds. Stevi Jackson and Sue Scott. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. 130-141.

The Silver Linings Playbook. Directed by David O. Russell. 2012. New York: The Weinstein Company. DVD.

Stoller, Aaron. Touchdown Celebrations to Come NFL Super Bowl LII Commercial, YouTube Video, 1:00, February 4, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KUoD-gPDahw.

Rich, "Compulsory Heterosexuality," 135.↩

Ardolino, 1987.↩

Soderbergh, 2012.↩

Stoller, 2018.↩

Ficarra and Requa, 2011.↩

For more information on other texts which have referenced Dirty Dancing, please see The Internet Movie Database's entry for Dirty Dancing, under "Connections."↩

Ibid., 139.↩

Ibid., 138-139.↩

The adjective straight is used in parentheses throughout this paper to make reference to the ways in which the identifier white men has, throughout contemporary American vernacular, and particularly in the 20th century, been employed to assume a heteronormative as well as American white male identity. With regards to the trope that "white men can't dance," a similar implication of sexuality has also been implied.↩

Saturday Night Live Transcripts, snltranscripts.jt.org↩

Ibid.↩

Eddie Murphy's Joke From 1987 Inspired The 'Carlton Dance,' Alfonso Ribeiro Shares, http://comedyhype.com/eddie-murphys-joke-from-1987-inspired-the-carlton-dance-alfonso-riberio-shares/↩

Eddie Murphy Raw, http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=eddiemurphyraw.htm↩

Eddie Murphy Raw, 1987.↩

Many AIDS scholars have addressed this relationship; however, the episode titled "The Fight Against AIDS" in the documentary miniseries The Eighties, which premiered on CNN on June 9, 2016, offers the most cogent depiction of the ways in which the AIDS epidemic caused widespread fear of homosexuality.↩

Moody, The Complexity and Progression of Black Representation in Film and Television, 48.↩

Please see Johnson's Appropriating Blackness for further discussion of this homosexual signifier.↩

Connell, "Hegemonic Masculinity," 832.↩

For more information, please see Louis Bien's article titled "Colin Kaepernick's movement continues just outside the walls of Super Bowl 52" on SBNation: https://www.sbnation.com/2018/2/4/16969134/super-bowl-protest-colin-kaepernick-will-players-kneel↩

Please see Dave Holmes's GQ article titled "Revisiting the Justin Timberlake-Janet Jackson Wardrobe Malfunction Minute-By-Minute": http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/music/a16020580/justin-timberlake-janet-jackson-super-bowl-halftime-show-wardrobe-malfunction/.↩

Dyer, "White Enough," 77.↩

Chow, "Every Little Thing He Does," np.↩

Johnny's embodiment of the hustler archetype is further explored in Gary Needham's article "Heteros and Hustlers: Straightness and Dirtiness in Dirty Dancing".↩

Fennessey, "The Two Goslings," np.↩

Ibid., 141.↩