The Camera-Dancer: A Dyadic Approach to Improvisation

Jennifer Nikolai, Auckland University of Technology

Abstract

How can the light-weight video camera in the hands of the improvising dancer, enhance compositional choices in moment-to-moment or retrospective decision-making in studio? I propose that the camera in the hands of the dancer moving and passing the camera between dancing subjects/objects is a form of improvisational investigation. I refer to this dyadic approach as camera-dancer, distinct from the tradition of the camera as archival instrument, in multimedia or interactive performance. The camera-dancer as instigator/provocateur opens perspectives towards composition otherwise not considered. In this paper I highlight approaches that moving image pioneers Maya Deren and Dziga Vertov held towards the camera and how this has informed studio improvisations myself and dance collaborators apply. Perhaps it is how we as dancing operators react to moments before, discoveries in the moment, a retrospective 'camera consciousness,' that enhances compositional openings as a form of camera dramaturgy.

Keywords: provocation, improvisation, camera-dancer, camera dramaturgy, motion capture

Introduction

The advent of inexpensive digital video and post-production tools has opened an array of potential pathways for exploration in the making processes of screendance. The accessibility and ease of use of cameras can stimulate artistic approaches that harness the immediacy of the technology as a reflective and iterative tool for the dancer and choreographer.1 The historical landscape of moving image includes a vibrant narrative of dance on screen, dance film, and dance for camera, which highlight the similarities between choreographic and cinematic practices.2 As a dancer, choreographer, researcher, and dance lecturer, I am interested in the shift in compositional inquiry that emerges when video cameras are introduced into dance improvisations in the studio.

My studio practice embraces a dyadic relationship between moving dancers with handheld cameras.3 My studio practice extends from the use of the hand-held camera to motion capture in order to interrogate dance improvisation and digital technology. I observe emergent approaches to problem-finding as dancers improvise with each other and with cameras.4 I allow for playfulness in our process, informed by Dziga Vertov's dynamic and experimental use and theorizing of the camera.5 A sense of naivety is encouraged between the dancers and cameras; this naivety arises from improvising with the technology as non-trained operators. Such dilettante-like treatment of the handheld recorders by dancers resembles Maya Deren's application of the amateur as a user of handheld cameras in her works.6 The playfulness and the naivety applied within my studio processes are grounded by Deren's essay, "Amateur versus Professional," and Vertov's notion of the kino-eye, which celebrates how the film camera surpasses the capabilities of the human eye. These filmmakers/theorists motivate the choreographic experimentation that has and continues to inform my practice.7 This article contextualizes theories on the moving camera that support the practice and position I present. Combining moving image history and theory alongside a discussion of my studio practice I propose that the camera in the hands of the improvising dancer is supported by a lineage of moving-image pioneers. I discuss my approach to working with hand-held cameras and motion capture technology, and turn to dramaturgical inquiry in order to catalyze the dyadic possibilities when camera and dancer meet.

Movement and time, tracing dance and the camera

For Henri Bergson, movement in time is distinct from the space that it occupies. Space covered is past, while movement is the present act of covering.8 Bergson's thesis on movement instants or positions, which he expounds in his book Creative Evolution, distinguishes between the dissolution of the pose (ancient movement), versus movement-as-flux (modern movement).9 Bergson attributes the position or pose to space, and the "whole that changes," to time.10 I propose that moving image dance can be considered an activity of transformation from the pose towards an uninterrupted flow as flux. In the text Dancefilm Erin Brannigan synthesizes the emergence of cinema and modern dance in motion pictures, in relation to Bergson's theories on movement.

Developments in turn-of-the-century technologies for film in 1895, as well as shifts in the practice of American modern dance, occurred concurrently with Bergson's development of theories on movement.11 As Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey were first experimenting with motion studies, the fascination with how still frames could become moving images shifted technologies in the field and led to the emergence of cinema and motion capture (mocap) technologies. In early explorations of motion on camera, the subjects included animals, athletes, and dancers. In his early experiments in the 1890s–1900s, Thomas Edison used dancers to test his equipment. Likewise, Georges Méliès used dance pieces in his film sequences. As Douglas Rosenberg has observed, "Technologies of the moving image as developed in the early 1900s enabled artists to explore multiple frames of reference and take advantage of the fluidity of cinematic time."12 With the conception of modern dance (less so than with traditional styles such as ballet), an emphasis on fluid movement qualities inspired changes to the photographic reproduction of dance.13 The two most prominent modern dance pioneers in this regard were Isadora Duncan and Loïe Fuller, who contributed to "popular entertainment technologies [producing] a 'moving image' that calls for a rechoreographing of the history of the moving image."14 Fuller utilized then-contemporary technology of motion picture and lighting implements, and her movement vocabulary and quality were ones of "flow" and of "flux" as opposed to poses and gestures.15 The combination of Fuller's use of popular entertainment technologies and her continuous movement quality produced a "moving image" that advanced the capture of movement in cinema.

As recording technologies developed and film became a dominant form of popular entertainment, Hollywood absorbed dance practices from vaudeville. Having begun his career on the vaudeville stage, Fred Astaire duplicated this perspective in his films, creating a cinematic experience that paralleled the proscenium experience for stage audiences. He insisted on full framing of the dancer's movements with no cutting away from the body. In contrast, Gene Kelly initiated an approach to camera work that favored the dancer while utilizing cinematic devices, including slow motion and the use of multiple perspectives, to enhance the gestures and drama that were being played out.16 The commercial interests of Hollywood filmmakers were orientated towards sound as opposed to modern dance and experimental approaches, such as those of Maya Deren who operated in the avant-garde space outside of American cinema. Deren contributed to a cinema that characterizes the instrument, the camera.17 Dance has informed cinematic practices with considerations of time, space, and form, just as the camera apparatus pushed the boundaries of what was recorded. It is no coincidence that the history of the moving image and the history of modern dance collide and align.

Pioneers Deren and Vertov: their philosophies towards the camera

In their respective practices, Maya Deren and Dziga Vertov exemplified philosophies towards the camera I have applied to develop the camera-dancer. Both pioneers were experimental in their own practice and wrote of the possibilities inherent in the use of mobile cameras. They were similarly intrigued by the potential of the untethered moving camera in terms of how it could, through its mechanics, see and record the kinetic vibrancy of the world in ways that were not possible with the human eye. Vertov, in particular, was invested in the notion of a camera that could capture the 'unawares' of daily life. His concept of the kino-eye is understood as "that which the eye doesn't see."18 One characteristic of Vertov's kino-eye was to avoid "filming 'unawares' for its own sake, but to show people without masks, without makeup; to catch them with the camera's eye in a moment of nonacting. To read their thoughts, laid bare by kino-eye."19

Deren argued for the value of a camera held by the amateur.20 Her 1959 essay "Amateur versus Professional" provides a point of reference for the role of the camera alongside the "mobile body" and "imaginative mind" of the dancer:

Cameras do not make films; filmmakers make films. Improve your films not by adding more equipment and personnel but by using what you have to its fullest capacity. The most important part of your equipment is yourself: your mobile body, your imaginative mind, and your freedom to use both. Make sure that you do use them.21

Deren's writing emphasized the experimental, amateur filmmaker, and the use of the camera to enhance cinematic potential, even to enhance dance. Although Deren did not always place the camera in the hands of the dancers she collaborated with, her camera work has been cited as an innovating art form, and is referred to as 'choreo-cinema.'22 Rosenberg echoes Deren's sentiment in his call for a camera that "catalyzes a reverence for the dance and focuses the act of seeing in a way that is quite different than the perceptual act that one might practice as a matter of habit."23 He refers to "camera-looking" as "an active performance that frames an event and elevates it while 'screening out' all other information."24 Dancers holding cameras while moving can choose to look at what they are shooting as they are shooting, or, alternately, footage can be viewed later. Either approach provides opportunities for immediate or retrospective viewpoints on improvised choices – on movement within the frame. Deren's sentiment and Rosenberg's suggestions lean towards the purposeful act of camera-looking.25 The camera operator dancing with the dancer(s) in the frame "is an act of reverence for that which is framed" choosing "essential and non-essential" therefore "presupposes the editing process."26 The intimate relationship between capturing in the space, within the frame, parallels the camera to the prosthetic, a "vision-prosthetic."27

Vertov made films during the early Soviet silent era, which is known for its application of montage techniques and graphic camera framing.28 As Steve Dixon observes, in Vertov's film Man with a Movie Camera (1929), "the camera is mounted in unusual and often extreme high angles and on moving automobiles."29 In one of the film's final sequences, Vertov shows the camera sitting on its tripod without a camera operator. It moves with a stilted walk, no joints in the lower limbs, implying it has done its job for the day. This anthropomorphic construction is a playful metaphor. In the film the human eye is repeatedly superimposed on the camera lens. "The film ends as it begins – with the camera – but the final point of view is attributed to the human eye, which continues to stare at the viewer, even after the iris completes its contraction."30 Vertov's camera implies a camera with a character, with enhanced capabilities.31 The appeal of Vertov's camera-consciousness is that he did not use hidden camera photography, "but makes a clear distinction between filming people off-guard and filming them with a hidden camera."32

The mobile camera gives us camera moves and camera angles – rhythm within the frame in the first instance. Deleuze writes that the moving camera is to be used only when it is essential to track, pan, and dolly in order to inform the work or image being seen.33 His notions of time go beyond the fascination of the composition within a fixed frame or a locked-off camera. Qualities of the moving camera reveal abstractions in movement. Deleuze's perspective on the mobile camera is that it does not just describe space through events, but also opens perception. For Deleuze, movement lives in montage. There is montage within the frame, across the shot, and in the linking of shots as the expression of unity in multiplicity throughout the system of the film. According to Deleuze:

In Vertov the interval of movement is perception, the glance, the eye. But the eye is not the too-immobile human eye; it is the eye of the camera, that is the eye in matter, a perception such as it is in matter, as it extends from a point where an action begins to the limit of the reaction, as it fills the interval between the two, crossing the universe and beating in time to its intervals.34

In human perception of matter, the interval is a delay between an action and a reaction that measures the infinite potentials and unforseeability of the reaction.35 In Vertov's montage theory, the interval no longer simply marks the distance between two consecutive images. The kino-eye is an objective perception, that which "couples together any point whatsoever of the universe in any temporal order whatsoever."36 Vertov's theory that intervals align any two points in the universe whatsoever became a point of departure for my improvisation approaches with hand-held cameras. I simultaneously identified parallels in digital capture, coupling together any points whatsoever through marker-based motion capture.

Contextualizing the camera-dancer process

I started the creation process for the camera-dancer in 2007 by using handheld (Flip) cameras as a pedagogical tool for tertiary dance students in composition studio classes. In 2009, I participated in Deakin Motion.Lab, a motion capture boot camp at Deakin University in Melbourne. The work at Deakin helped me to develop research into capturing digital movement data to use in non-digital settings (i.e. improvisations in the studio). I integrated into my practice a number of concepts embedded in motion capture technology. Firstly, the concept of the Omniscient Frame stems from the lack of a proscenium-like orientation to the subject, as the array of cameras within the capture volume are not fixed and not determined by shot type.37 Secondly, one can attach a virtual camera to any still object or moving object marker inside the capture volume area. This can enable the tethered camera to move with and as a response to the moving body. A camera can be 'virtually' mounted anywhere on the moving body or within the capture space during post-production. To do so, the motion that has been embedded as motion capture data in 3D virtual space—a virtual camera—generates a dancer inside the screendance itself.

Tethered cameras

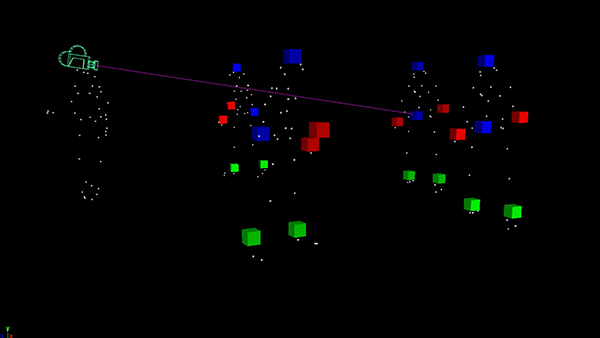

Motion Capture visualization; camera tethered to Dancer 1 head marker.

During my creative process, a key question that emerged was: how might an accessible video camera placed in the hands of, or tethered to, the body of the dancer, motivate dancers' movements, based on such variables as the moving dancers' point of view (POV), camera placement (held by the dancer or shooting the dancer), or what the dancer encounters in the frame (the viewfinder)?

Months later in a studio workshop with six dancers and four video cameras, we set provocations for improvisations. We used a green Thera-band38 to tie two cameras together, and we set a task for the two cameras (bound together) to be passed between two operators. The dancers being shot would later shoot. This gave the dancers the opportunity to improvise for and with the cameras, and established conditions for what would become a task we called Bound Together.

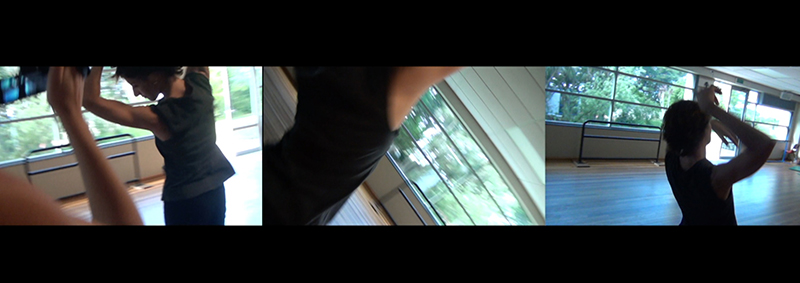

Dancers Xinia Alderson, Jane Carter and Aya Nakamura studio footage; Thera-band bound to two Flip cameras connecting two dancers holding tethered cameras..

In Bound Together, two dancers, holding cameras restricted by the band that attached them, moved in tandem. The pair had the freedom to travel amongst the other dancers (who were not operating cameras). The attached, resistant fabric simultaneously restricted and subtly directed their choices. The tension was not only between the cameras bound by resistant fabric, but also the potentially conflicting pathways the dancing operators wished to travel in.39

The forced relationship between cameras and dancers afforded multiple perspectives, and restricted movement pathways and dynamics between the improvising dancers. The camera-operators bound together offered a compositional vantage point. They could dance and see through their eyes, through their own viewfinder, or through the other operator's viewfinder.

Dancer Jennifer Nikolai; captured by three untethered handheld cameras in a studio improvisation.

The camera-dancer became an observer, a participant, a partner, and an instigator, distinct from the conventional camera as archival machine in performance and rehearsal. The role of the camera-dancer shifts the dynamic between camera and mover in multiple ways. It asks a camera-dancer to be dramaturgical, in that it uses moving image capture (of moment-to-moment decisions) to inform or respond to improvisational decision-making. In an improvisation, the dancer can make an immediate decision to align an action experienced live with an action captured on camera (seen through the viewfinder), in order to deliberately frame a moment or movement. When retrospectively reviewing footage of an improvisation, dancers may find connections or contrasts between two seemingly distant moments. Improvisers can parallel or juxtapose movement quality, spacing, or timing, or align to what they think the operators might shoot in the improvisation. In looking at the footage retrospectively, two seemingly distal or proximal images can inform a specific choice for the next improvisation. This option to look through the viewfinder is significant as a tool while improvising with a capture apparatus, because it encourages immediacy and supports reflection.

The camera offers perspectives as it pans, zooms, frames, and reveals openings for the improviser to work with. As cameras are passed between operators, movers without cameras cannot entirely anticipate what will be shot within the improvisation. The improvisers holding cameras therefore respond to one another's compositional choices such as depth of field, POV, or framing.40 The dyadic relationship between the dancing and operating opens emergent compositional opportunities to dancers and camera-dancers, otherwise not apparent.

Dramaturgical intentions in camera perspectives and structuring

Choreographic processes using moving image do not always begin with a pre-determined structure, but rather, structures emerge in concert with the shaping of ideas.41 Through dramaturgical approaches that involve trial and error, collaboration and shared facilitation, a decentering of established hierarchies in the roles of production takes place.42 My approach to dramaturgy as a form of live and digital dialog occurs within improvisation as integrative and emergent. It involves an interactive expansion of shared processes. It opens awareness to possibilities and trajectories revealed by shared forms (live and digital). I refer to dramaturgy as sensitive to the dynamics that emerge within the creative process through experimentation. The integrative character of my practice blends theoretical with physical exploration from a range of sources and perspectives that in a cumulative decision-making process create emergent trajectories. The interactive element of my practice involves the physical, intellectual, and imaginative engagement of makers throughout the process, who in turn transform physical and conceptual ideas into material.43 These characteristics guide dramaturgical intention towards improvisational inquiry with cameras.

While improvising as a camera-dancer propositions that emerge become themes, possibilities, juxtapositions, and trajectories for further provocations. The term 'provocation' in this context is taken from Edward De Bono's methods of lateral thinking adapted to re-arrange information (e.g. camera-dancer improvised material), in order to "bring new features into existence" in an emergent process.44 Provocations led by the camera-dancer dyad emerge through the improvisations, and through viewing footage in real-time or retrospectively. All the unknown spaces, the gaps in between dancing and looking or not looking, close-up or wide-shot, but holding and negotiating between camera and mover, these are the moments of provocation. Moments may be small, subtle, and unpredictable. Provocations lead us to "where to next?" when investigating compositional and dramaturgical possibilities.

Hilary Preston proposes that we expand choreographic potential to include the elements of camera operation and composition.45 Her thinking has been a catalyst for my practice and experimentation of parallel compositional principles with a dramaturgical approach. Preston suggests that choreography and camera work are symbiotic.46 The choices that are available to the moving camera operator to question POV, angles, and camera movement, allow him/her to manipulate spatial relationships within and outside of the frame, further informing decision-making while improvising. With a camera in hand, the dancer can shape with or around bodies in space, in order to consider how the role of the frame helps to develop dance 'looking' and camera composition. Further,

the unique relationship that is created between the dancer and his or her environment by the single viewpoint of the film camera can enable this spatial precision to be substantially developed – either through the interpretation of existing choreography by careful camera positioning, aspect ratio and filming site selection or, more excitingly, through the creation of choreography specifically designed to exploit the film medium in this way.47

A key advantage offered by the Flip cameras for camera-dancers was that the open viewfinder/screen enabled the dancer to refer to the frame or to disregard it while improvising. Wide, medium, and close-up framing allowed for selection or delegation of what existed within or outside of the frame. Brannigan situates the close-up as being significant in the history of dancefilm, as it has provided a "new cine-choreographic terrain."48 In focusing on body parts, body gestures, or facial expressions, dancefilm has the capacity to investigate micro-choreographies on screen.49 Rosenberg discusses how: "A gesture that on stage may seem small and insignificant may become, when viewed through the lens, grand and poetic, while the dancer's breath and footfalls may become a focal point of the work."50 These nuances are experienced by the dancer in the intimate, shared space of the improvisation. The close-up allows the fellow improviser as well as spectators to engage with micro-choreography, and invites a focused respect for the micro—the nuance, the slow breath—unheard, to be seen.

Framings and re-framings: Deleuze and the mobile camera

Deleuze attributes the subjective camera to those camera actions that enhance more than just the act of following a character's movements (description of space) subordinated to the function of thought. The subjective camera in this instance allows the camera to engage with the indiscernible, in its array of functions, moving towards camera-consciousness.

a camera-consciousness, which would no longer be defined by the movements it is able to follow or make, but by the mental connections it is able to enter into. And it becomes questioning, responding, objecting, provoking, theorematising, hypothesising, experimenting, in accordance with the open list of logical conjunctions ('or', 'therefore', 'if', 'because', 'actually', 'although').51

According to Daniel Frampton, Deleuze recognizes Alfred Hitchcock as introducing what he refers to as the mental image into cinema. This is where the film image ''is able to catch the mechanisms of thought, while the camera takes on various functions strictly comparable to propositional functions."52 Can the camera-dancer therefore be advantaged by pushing the mobility of the camera, "hypothesizing" while moving as/with the subjective camera?53 This camera-consciousness is not solely held by the apparatus, or the performing body – it is in the space, indiscernible, subjective, between and amidst. The perception of space and of space moving, as chosen by the camera-dancer, opens possibilities for improvisational approaches responding to space, between and amidst. Deleuze also proposes that

the fixity of the camera does not represent the only alternative to movement. Even when it is mobile, the camera is no longer content sometimes to follow the characters' movement, sometimes itself to undertake movements of which they are merely the object, but in every case it subordinates description of a space to the functions of thought.54

Deleuze's reference to the "fixity of the camera'' is not simply a distinction between a subjective and objective camera; rather, he points to the indiscernibility between the subjective and objective, which "endow the camera with a rich array of functions," and in this regard, provide "a new conception of the frame and reframings."55 This speaks to the interchange between subjective and objective perspectives proposed by the camera-dancer.

What next? The camera/dancer dyad in practice

Maya Deren described "the incalculable and uncategorised kinds of movements possible with the handheld camera in direct relationship to the body."56 In her work and writings, she recognized that the camera can be utilized as a creative instrument in the process of making:

to think of the mechanism of the cinema as an extension of human faculties is to deny the advantage of the machine. The entire excitement of working with a machine as a creative instrument rests, on the contrary, in the recognition of its capacity for a qualitatively different dimension of projection.57

Deren describes her model of cinema as a vertical structure as opposed to a horizontal structure.58 Verticality lends itself to a more poetic structure, whereas the horizontal is associated with drama, moving action, and circumstance, one into the other. In an improvisational provocation with a handheld camera, the camera's relationship to the body in space, with multiple and diverse perspectives, allows the viewer to empathize without narrative structure.

Such an approach to constructing empathy appears in Hilary Harris's film Nine Variations on a Dance Theme (1966). The dance phrase, which Bettie de Jong performs repeatedly, recalls Talley Beatty's movement in Deren's A Study In Choreography For Camera (1945). A main focus of Nine Variations is the role of the camera in shaping the space of the dancer. When the film begins, De Jong is seen dancing from a distance; by the end of the film, we have travelled through mid-shots to extreme close-ups from multiple angles. Further, as the film progresses, a shift occurs; the camera starts to move in opposition to the dancer as her movement phrase rotates in place. De Jong executes a long, languid movement phrase commencing from the floor, spiraling in a controlled sequence to a standing extension. Then, she returns to the floor to finish in the same position she began in. The phrase is looped nine times, and the movement remains consistent. It is movement of the camera that is used to construct nine variations of the phrase by never repeating its position or spatial pathways. In this film, the compositional considerations are in the hands of the mobile camera operator. I suggest that as a viewer I become increasingly empathetic by experiencing poetic variations, abstractions not otherwise possible through live performance or a proscenium documentation of the recorded phrase. The initial real-time pace of the shots reveals the full dance phrase, her movement quality, and her relationship to the studio space. The edited sequence, varied, later accelerates, punctuating segments of De Jong's body in motion. With fast cuts and framed fragments of the dancing body natural light in the studio illuminates parts of her torso. We still recognize her, her qualities and experience a shift in tone as we retain the vision of the full movement phrase. A Deleuzian perception of space moving is not determined by the dancer holding the camera here, but by the camera that dances amidst her. So in this instance, the piece presents the leading possibility of what a dancing operator could offer if the framed phrases were formed by the mover. The spatial and temporal variations open the viewer to kinesthetic empathy as if we move alongside and sense that space and light and textures, with De Jong.59

Study #1 still with dancer Jennifer Nikolai and cloth simulation.

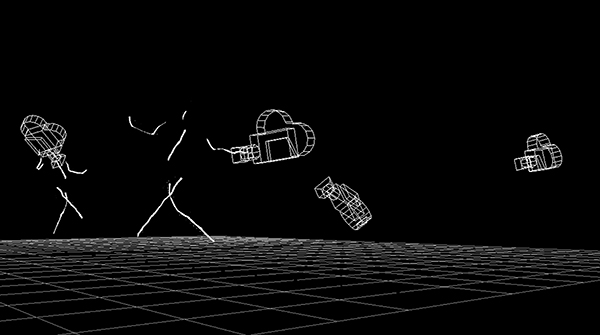

In my recent practice (2015), I have returned to motion capture technology and the resulting data as a form of camera dramaturgy. In studio improvisations through to post-production, an inquisitive and reflective camera-consciousness emerges from making and viewing the motion capture data. Study #1 is a co-choreography with animation artist Gregory Bennett. The studio improvisations, as well as the data capture, visualization, and post-production decision-making processes were collaborative and iterative.60 A series of virtual cameras were created in post-production and choreographed around the improvised performance. Each iteration occurred as trial-and-error through dialog and reflection, during which we made adjustments and choices before embarking on the next iteration.61 Our collaboration has continued with Study #2, currently in post-production, in which we have returned to the tethered camera as a catalyst for capturing the moving body from perspectives not otherwise considered.

Study #2 multiple tethered cameras to one dancer (duplicated).

In this work with Gregory, I am drawing inspiration from Deren's film The Very Eye of Night (1958). Deren's film is an example of freeing dancers from gravity via the post-production film technique of optical printing. The process of filming with a hand-held camera on a dolly combined with optical printing in post-production created the effect of dancers floating like stars in space. Deren's untethered camera generated raw footage that was further manipulated in post-production and editing by combining and re-combining layers of dancers against a constellation. Her dancing subjects were superimposed on a black background so the effect of the floating dancer mirrored that of the stars within the constellation.62

There are interesting parallels between optical printing and motion capture. In both techniques, the cameras are untethered: a virtual camera can be created at any point in space and anywhere in the capture volume. The virtual camera can move at any point in that x, y, z space. With motion capture data, the floor is not recorded as such. Only the movement data of the dancers is captured. In motion capture, cameras are mounted from any angle anywhere and this enables greater flexibility than in Deren's time. Thus, we have a wealth of options while still creating an illusion of moving flexibly through 3D space.

Study #2 as an iteration from Study #1 has similar provocations in the process of creation, capture, and post-production decisions. These options also extend to the 3D visualization of the "large" camera. The difference in Study #2 is that the dancers' captured movement is used to directly drive the camera visualization by virtually tethering the camera to markers on the digital dancers' bodies.

The camera in Study #2 moves through a 3D geometric map with pathways that resemble a dancer in a jump, mid-turn, or inverted – because it is a dancer with a camera visualization.63 The camera is attached to her body. The camera in this piece, as in The Very Eye of Night, cajoles with degravitation not amidst the constellation, but amidst fellow performers. The multiplication of dancers in Study #2 is simultaneously a post-production choice to replicate the one moving figure, caught in an improvisation. This dancer is duplicated to be tethered to herself, as well as virtual cameras tethered to her duplicated body. That moving dancer is my duplicated avatar, in my improvisation.

Dramaturgical thinking in dance, involving technologies and interactive designs from the conceptual starting point, requires a different environment for its evolution.64 In my practice, the inquisitive and interactive characteristics of camera-dancer improvisation, with dramaturgical intention opens a recurring relationship between dancers and their cameras. These are the cameras that we hold and shoot. They improvise with us as subjects and objects. Taken to motion capture, these cameras enable myriad possibilities between dancer and camera, and facilitate an iterative, generative process of inquiry.

Biography

Jennifer Nikolai (PhD) is a contemporary dance practitioner, researcher, and Senior Lecturer. Her studio-based, emergent methodology informs live and digital interactivity in performance making and staging. Her research spans mobile camera improvisation, motion capture and VR and the practice of pedagogical critique across a range of tertiary teaching contexts. She conducts research in Canada and New Zealand, her country of origin and her country of residence, respectfully. Jennifer lectures and supervises postgraduate research students in the School of Sport and Recreation and in the School of Art and Design at Auckland University of Technology in Auckland, New Zealand.

Email:

References

"A Study in Choreography for Camera." Maya Deren. 3 min. USA, 1945.

Adolphe, Jean-Marc. "Dramaturgy of movement" Ballet International 6 (1998): 29-27.

Behrndt, Synne K. "Dance, Dramaturgy and Dramaturgical Thinking." Contemporary Theatre Review 20.2 (2010): 185-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10486801003682393

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Translated by Arthur Mitchell. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Publishers, 1944.

Birringer, Johannes. "Dance and Interactivity." Dance Research Journal 35.2-36.1 (2004): 88-111.

Brannigan, Erin. Dancefilm; Choreography and the Moving Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195367232.001.0001

Carroll, Noël. "Toward a Definition of Moving-Picture Dance." Dance Research Journal 33.1 (Summer 2001): 46 - 61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1478856

Cowie, Billy. "Framing the Body." Paper read at Screendance: The State of the Art at Duke University, Durham, NC. 2006.

Delbridge, Matt. Motion Capture in Performance: An Introduction. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Pivot, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781137505811

Deleuze, Gilles. 1986. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. London, New York: The Athlone Press. Original edition, 1983.

____. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Dixon, Steve. Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theatre, Dance Performance Art and Installation. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007.

Dodds, Sherril. Dance on Screen; Genres and Media from Hollywood to Experimental Art. Hampshire, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004.

Frampton, Daniel. Filmosophy. London & New York: Wallflower Press, 2006.

Genné, Beth. "Dancin' in the Rain: Gene Kelly's Musical Films." In Envisaging Dance on Film and Video. Edited by Judy Mitoma. New York and London: Routledge, 2002. 71-77.

Greenfield, Amy. 2002. "The Kinesthetics of Avant-Garde Dance Film: Deren and Harris." In Envisaging Dance on Film and Video. Edited by Judy Mitoma. New York and London: Routledge, 2002. 21-26.

Hagood, Ed Thomas K., ed. Legacy in Dance Education; Essays and Interviews on Values, Practices, and People. Amherst, New York USA: Cambria Press, 2008.

Hee Jong, OK. "Reflections on Maya Deren's Forgotten Film, The Very Eye of Night." Dance Chronicle. 32.3 (2009): 412-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01472520903276750

Hicks, Jeremy. Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film. London, New York: I.B. Taurus & Co Ltd, 2007.

McCarren, Felicia. Dancing Machines: Choreographies of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2003.

McPherson, Bruce R. ed. Essential Deren; Collected Writings on Film by Maya Deren. Kingston, New York: McPherson & Company, 2005.

McPherson, Katrina. Making Video Dance; A step-by-step guide to creating dance for the screen. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

Michelson, Annette. Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1984.

Nikolai, Jennifer. The Camera-Dancer Dyad: A critical, practical dialogue of virtual and live studio methodologies. Doctoral Thesis, AUT University, Auckland, NZ. 2014.

____. Camera Dramaturgy: A critical, practical dialog between dance and camera studio methodologies, International Conference on Dance Education (ICONDE). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2014. Publication of the conference proceedings will be forthcoming in 2016.

Nikolai, Jennifer, and Gregory Bennett. "Stillness, Breath and the Spine - Dance Performance Enhancement Catalysed by the Interplay between 3D Motion Capture Technology in a Collaborative Improvisational Choreographic Process." Performance Enhancement & Health 4 (2016): 55-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2015.11.003

"Nine Variations on a Dance Theme." Dir. Hilary Harris. 13 min. USA, 1966/67.

Petric, Vlada. Constructivism in Film: The Man with the Movie Camera: A Cinematic Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Preston, Hilary. "Choreographing the frame: a critical investigation into how dance for the camera extends the conceptual and artistic boundaries of dance." Research in Dance Education 7.1 (2006): 75-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14617890600610752

Rodowick, D.N. Gilles Deleuze's Time Machine. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003.

Rosenberg, Douglas. "Video Space: A Site for Choreography." LEONARDO 33.4 (2000): 275–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/002409400552658

____. "Proposing a Theory of Screendance." Paper read at Screendance: The State of the Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, 2006.

____. Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Sawyer, Keith. "Improvisation and the Creative Process." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 58.2 (2000): 149-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199772612.001.0001

"The Very Eye of Night." Dir. Maya Deren. 15 min. USA, 1958.

Towers, Deirdre. "Inventions and Conventions." Paper read at Screendance: The State of the Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, 2006.

Vertov, Dziga. Man with a Movie Camera. Blackhawk Films Collection. Image Entertainment, 1929, DVD 1998.

____. Articles, journaux, projets de Dziga Vertov. Paris: Union générale d'éditions, 1972.

Williams, David. "Geographies of requiredness: Notes on the dramaturg in collaborative devising." Contemporary Theatre Review 20.2 (2010): 197-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10486801003682401

Wood, Karen. "Audience as Community: Corporeal Knowledge and Empathetic Viewing." The International Journal of Screendance 4 (2015): 29–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v5i0.4518

Notes

Approaches to using the camera as a pedagogical tool are discussed further in a paper presented to the International Conference on Dance Education. See: Jennifer Nikolai, "Camera Dramaturgy," forthcoming.↩

A range of discussions and critiques arose as video cameras became more accessible and affordable. Suggestions such as Douglas Rosenberg's did enlighten audiences and makers that "Since the advent of film…cinema and dance have engaged in an almost unbroken courtship, each appropriating techniques and styles from the object of affection" ("Video Space," 275). To follow were 'definitions' encompassing dance and cinema in complimentary forms, including Noël Carroll's shaping of the term "moving-picture dance" in "Toward a Definition," as well as Hillary Preston's writing on "how dance for the camera extends the conceptual boundaries of dance" in "Choreographing the frame." The response that resulted is in the form of endless interdisciplinary works and outcomes between live and digital forms. In this article, I am most interested in early experiments and their lasting impact. I have identified examples including early moving image experiments in Deren's works A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945) and The Very Eye of Night (1958) as well as Harris's Nine Variations on a Dance Theme (1966).↩

The initial emphasis was placed on how to 'compose,' considering the elements and devices surrounding camera-based provocation. Initial exercises developed an awareness of trust and partnership, sharing space, traveling through space (range of levels, dynamics, pathways) and sharing focus while holding the camera and dancing with 'other' dancers and cameras. I also proposed exercises that questioned the notion of clock time (stillness and temporal transitions) and how holding cameras while dancing occupied 'time,' and focus.↩

Problem-finding refers to studio 'making' approaches in a process that is collaborative and emergent as in Keith Sawyer, "Improvisation and the Creative Process."↩

See Annette Michelson, Kino-Eye.↩

See Bruce R. McPherson, Essential Deren.↩

It was within my PhD candidacy at AUT (Auckland, New Zealand) that I conducted five years of work-shopping dancers with handheld cameras.↩

Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1, 1.↩

A concept articulated through Deleuze in Cinema 1, and in Brannigan, Dancefilm, 22.↩

The whole that changes in Deleuze's time-image is developed and contextualized alongside Deleuze's movement-image, within Cinema 2.↩

As outlined in Deirdre Towers' description of the gap in moving image technology and dancing subjects in "Inventions and Conventions."↩

Rosenberg, Screendance, 58.↩

See Erin Brannigan's recapitulation of American dance historian Nancy Lee Chalfa Ruyter's identification of the shift in physical culture from a private and amateur activity, to movement as choreographic, outside of the institution of ballet (and the pose). Dancefilm, 22.↩

See Brannigan, 22.↩

Idem., 38. Brannigan develops a detailed description, and suggests that Fuller's dance was composed of her moving arms, with a circle of silk panels from her neck to her arms, to create flow in her dance through the fabric. This material (silk panels) surrounded the dancer, creating fluid movement in constant transformation. The transformative, moving fabric was coupled with multiple colored lighting effects to create a magical, theatrical dance spectacle captured by motion picture, distributed by Edison Manufacturing Company in 1895. The kinetic range in these large, upper body movements exemplifies the abstract, continuous flow and enlarged gestures, in contrast, for example, to balletic gestures repeated as traditional in origin and recognizable to dance audiences.↩

See for example the slow motion dream sequence in Carefree (1933), the dancing shadows in Swing Time (1936), and the mobile camera and a range of camera angles in Singin' in the Rain (1952). Beth Genné, "Dancin' in the Rain," 73.↩

Brannigan, 103.↩

Michelson, 41.↩

Idem., 132.↩

Maya Deren worked with minimal resources when she began filmmaking and she continued to ask questions of the camera that pushed her practice.↩

Katrina McPherson, Making Video Dance, 18.↩

Sherril Dodds, Dance on Screen, 7.↩

Rosenberg, Screendance, 69.↩

Rosenberg, "Proposing a Theory of Screendance," 14.↩

Rosenberg, Screendance, 69.↩

Ibid.↩

Ibid.↩

See Deleuze, Cinema 1, 33 – 42, chapter section on "The Soviet school."↩

Steve Dixon, Digital Performance, 66.↩

Vlada Petric, Constructivism in Film, 127. Although this and other films are located within historical, Soviet political objectives, I refer to Dziga Vertov as an influential practitioner and writer, on his "kino-eye," the eye of the camera that accentuated the capabilities of the camera improving on the human eye's perceptive capabilities.↩

Vertov operated with an enthusiasm for the playfulness of the motion picture camera and its capacity to inform and augment as it played, coerced, and cajoled with the games and industry of everyday spectators and participants.↩

Jeremy Hicks, Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film, 24.↩

Deleuze, Cinema 1, 25–26.↩

Idem., 41.↩

D. N. Rodowick, Gilles Deleuze's Time Machine, 60.↩

Vertov, "Articles, journaux, projets de Dziga Vertov," 126-127.↩

See Matt Delbridge, Motion Capture in Performance.↩

A Thera-band is an elastic fabric often used for rehabilitation or strength and conditioning purposes for dancers. The color of the band determines the factor of resistance. A green Thera-band provides minimal but ample resistance and is strong enough not to break easily.↩

Partnered cameras shot either a different perspective of the dancers in the space, or a slight variation of the image recorded by the camera hovering nearby. The resulting footage therefore revealed both massive variations on the dance material shot in the space, or the slight variations of the non-operating dancers and the other dancing operator, attached.↩

These three examples are compositional offerings a camera has to offer to a dancer, which parallel the choreographic compositional considerations implicit in the dancer's body practice, also offered through her training and her relationship to space.↩

See Synne Behrndt, "Dance, Dramaturgy and Dramaturgical Thinking."↩

Jean-Marc Adolphe, "Dramaturgy of Movement," 27.↩

See David Williams, "Geographies of requiredness."↩

Ed Hagood, Legacy in Dance Education, 203.↩

Preston, Choreographing the frame.↩

Ibid., 75.↩

Billy Cowie, "Framing the Body," 38.↩

Brannigan, 39.↩

Idem., 45-46.↩

Rosenberg, "Video Space," 277.↩

Deleuze, Cinema 2, 23.↩

Daniel Frampton, Filmosophy, 63.↩

Refers to Frampton's writing on Hitchcock's camera-consciousness combined with my links to Deleuze (Cinema 2, 23) and the potential in the camera-dancer.↩

Deleuze, Cinema 2, 23.↩

Ibid.↩

Amy Greenfield, "The Kinesthetics of Avant-Garde Dance Film," 26.↩

McPherson, Essential Deren, 25.↩

Brannigan, 104–105.↩

Kinesthetic empathy in this context refers to Karen Wood's loose definition of the term as the sensation for the screendance viewer, of moving while viewing. See Wood, "Audience as Community," 29.↩

Study #1 is a dance and motion capture collaboration by Gregory Bennett and Jennifer Nikolai. The piece explores choreographic prompts and improvisation utilizing 3D digital motion capture technology. The live dancer is inscribed into a 3D visualization, which references both drawing practices such as the sketch, and experimental animation, particularly Len Lye and Norman McLaren and their studies in moving image and sound. Iterations from studio generated material were taken to post-production. The sequencing of outcomes in post-production determined what prompts we then took back to studio. As an iterative process, this sequencing determined in the final stage, when we would set our decisions, towards reaching our final outcome; a screendance piece.↩

Study #1 trailer: https://vimeo.com/133319833. Study #1 has been screened in the International Screendance Festival 2015 (North Carolina), the Edmonton International Film Festival 2015 (Edmonton, Canada), the Tempo Dance Festival 2015 (Auckland, NZ) and in the Dance on Camera Festival (New York) 2016.↩

See OK Hee Jong, Reflections.↩

Study #2 test: https://vimeo.com/157387789, password: dance↩

Johannes Birringer, "Dance and Interactivity," 89.↩