Watch films, watch dance films, watch more dance films

Katrina McPherson, Independent Artist, Scotland

Keywords: screendance, Internet, on-line viewing, curation, contextulization

Whatever your relationship to screendance—whether making, curating, or writing about the genre, or coming across it for the first time—accessing a wide range of work represents an essential aspect of engagement with the medium. Whereas screendance makers and audiences previously depended on relatively rare public screenings in theaters and infrequent television broadcasts, and the shipping or schlepping of VHS tapes/DVDs across continents was par for the course, nowadays the Internet provides an always-on, global site for the dissemination and discovery of screendance works.

However, knowing what exists on the Internet and how to find it presents its own challenges and so the curating and contextualization of new and historic screendance available through the Web would seem to be a useful, if not essential accompaniment to this expanded platform. With that in mind, I was pleased to be invited by the editors of this journal to take a personal 'frolic' through screendance available to view on the Internet and to write about it here.

My exploration started with where things kicked off for me 30 years ago, and that was with a film documentation of Yvonne Rainer performing her seminal postmodern work Trio A, captured in this film produced by Sally Banes in 1978. The frame remains wide throughout, showing the whole of Rainer’s body as she performs the five minute long choreography for the camera on a studio stage, then certain details are repeated in closer shots, giving more information about specific phrases of movement. This single camera documentation was pretty much the only piece of filmed postmodern—or indeed modern—dance available on VHS in the library at Laban when I was a student there in the mid-1980s. I viewed it again and again in those days, intrigued and inspired by the simplicity of the image and the non-virtuosic concept behind Rainer's dead-pan performance.

Screenshot. Trio A Chor. and Perf. Yvonne Rainer. Cinematogr. Robert Alexander Prod. Sally Banes. 1978.16mm.

When I search for the Trio A film online today, I find it and also a new discovery from a decade before, which is Yvonne Rainer's short Hand Movie (1966). This was the first film that Rainer herself made, the result of being immobilized in a hospital after major surgery. Here the camera takes the role of a neutral witness, a single shot framing Rainer's hand as it bends and points and smooths in a series of uninflected everyday gestures, resonant of the whole body movement sequences of her better known stage work and echoed here in this simple filmic treatment.

Screenshot. Hand Movie. Chor. and Perf. Yvonne Rainer. Cinematogr. William Davis. 1966.16mm.

In a public forum recently, artist and scholar Douglas Rosenberg made the following observation: "For some of us, we can mark a definitive point of origin; a moment when 'screendance' as we know it began."1 Reflecting on this notion, I can pinpoint exactly when that moment was for me. Or, perhaps more accurately, the moment when my gut instinct about the potential of the collaboration between dance and the moving image became recognizable in a definable art-form, even if its name remained fluid for a good while longer. Around 1990, having worked pretty much in isolation for five years, and having had very little exposure to screendance other than my own, I attended IMZ Dance Screen Festival in Frankfurt. It was there that the moment of definition happened for me, and the work that triggered it was Roseland (1990).

Directed by Walter Verdin, Octavio Iturbe, and Wim Vandekeybus, the film is made from the material of Belgian dance artist Vandekeybus’s first three live works for his company Ultima Vez, resetting the choreography in the atmospheric location of a deserted Brussels cinema. On its release, Roseland received the Dance Screen Award for "transforming the theatrical energy of the stage choreography into a dynamic screen experience, using a full range of cinematic techniques."2 In doing so, it set the bar for the next decades of screendance making.

Online, I find an excerpt of Roseland lasting just over seven minutes. It is the thrilling stones section, full of shifting relationships and split-second timing. Returning to the work today, I am as captivated as ever. The relaxed use of handheld camera, the rhythmic editing leading from wide images that situate the choreography in the architecture to close up details of body parts—a hand gripping an arm, faces looking outward—Roseland utilizes all the elements that contribute to creating a dynamic and engaging screendance work. It displays an understanding by the artists of the different types of shots and how these can frame the human body, the ability of the camera to bind us to the heart of the action, the rhythmic construction through editing of time and space that is unique to the screen work, and which draws us with it, through variations of pace and flow. All this is contained in Roseland and, 25 years after it was made, it can still teach much about making dance for the screen.

Screenshots. Roseland. Dir. Walter Verdin & Wim Vandekeybus Chor. Wim Vandekeybus Comp. Thierry de Mey and Peter Vermeersch Perf. Ultima Vez. 1990.

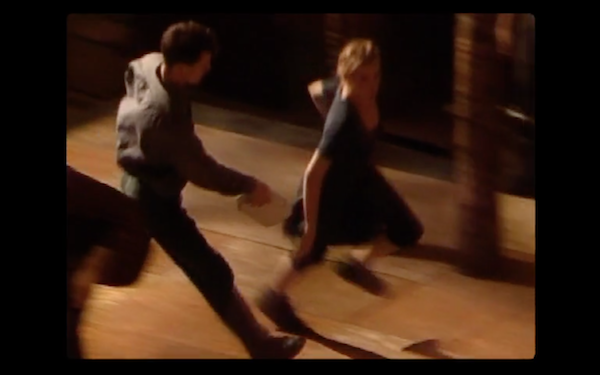

A series of links lead me to another screendance work based on dance made for live performance. This time, it is the short 10 Men, which features choreography by the UK dance artist Nigel Charnock, captured in rehearsal by filmmaker Graham Clayton-Chance. Here, largely observational monochrome images are presented to create a raw, yet unified aesthetic, edited to a poppy bossa nova music track.

What speaks so eloquently are the performances: Clayton-Chance's handheld lens captures the infectious, sweaty exuberance of the ten men as they rehearse Nigel Charnock's quick-footed, witty choreography. It's quite an ensemble, each performer is distinctly individual, yet all come across as ordinary blokes, and fun-looking ones at that. Viewers familiar with Nigel Charnock's memorable on-screen roles, most notably in David Hinton's DV8 films, can perhaps detect echoes of his performances in the choreography, as embodied in this eclectic group of dancers. That Charnock is no longer living makes these men's lively and committed dancing all the more poignant.

This is such a simple film, yet there is a joyful immediacy that feels important, not least as a record of—and a subtly flamboyant tribute to—the legacy of a brilliant dance artist whose work might otherwise be lost. Sometimes this aspect of screendance is overlooked—that it can provide cherished traces of moments and people now gone.

Screenshots. 10 Men. Dir. Graham Clayton-Chance. Chor. Nigel Charnock. Perf. The Nigel Charnock Company. 2012.

While talking of performance, I want to mention a series of micro-films by the influential video artist Joan Logue, available on YouTube. Produced mainly in the 1980s, Logue's 30 second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists originate from a period when artists working in the medium of video often made work that commented on the nature of television. This series of fake advertisements features seminal artists from the later decades of the 20th century. Perhaps stretching the definition of 'screendance' a step too far by including it here, in Logue's work there is a simplicity of concept, carried through with intelligent humor, that can inspire us all as we work with performance on screen.

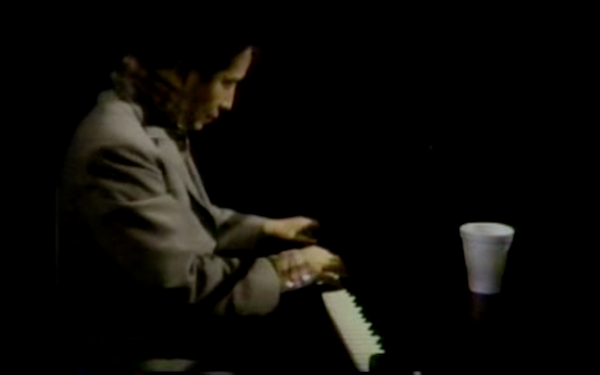

A single still wide shot frames Nam June Paik as he takes his place at the piano. He places his Styrofoam cup deliberately on the top of the piano, sits down and hesitates, before crashing his head onto the keyboard. Steve Reich's 'advertisement' features intercut close up shots of two pairs of clapping hands creating a texture of polyrhythmic images. Laurie Anderson is represented playing percussion on her body, with head, mouth, and hands all involved. My favorite is a piece delivered to camera by John Cage, whose measured, gentle voice tells us sweetly and solemnly how his father told him that "Your mother is right ... even when she is wrong." Brilliant!

Screenshot. 30 Second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists. Dir: Joan Logue. 1982-83. Nam June Paik

The Internet is increasingly providing us with the opportunity to watch dance films from across the last century, as more archival work is made available. I am very happy to re-discover Shirley Clarke's Bridges Go Round on YouTube, a film which is often programmed within the screendance canon, and rightly so. Part of an avant-garde of independent film-making in America in the 1950s, Shirley Clark's background was as a dancer and choreographer before studying film and she brings a kinaesthetic sensibility to her short films. A number of Clarke's early films featured modern dance-makers such as Daniel Nagrin (Dance In the Sun, 1953) and Anna Sokolow (Bullfight, 1955). At present, I can't find either of these films to view on the Internet, however Bridges Go Round offers us an important insight into Clarke's contribution to the evolution of screendance, as camera movement, montage, and super-imposition fuse to create an exquisite cine-choreography of the inanimate and iconic Brooklyn Bridge. The film exists with two different soundtracks, added at the time of production, to be seen one after another. Teo Macero's evocative jazz sound score contrasts Louis & Bebe Barron's haunting electronic score and it is both enlightening and educational to compare the effect of the different soundtracks on the experience of watching the film.

Screenshots. Bridges Go Round. Dir. Shirley Clarke. Comp. Teo Macero/ Louis & Bebe Barron. 1958. 16 mm.

Developments in technology often capture the imagination of artists, typically resulting in shifting paradigms of production. Lately, super high definition cameras (such as the Phantom) have invited a new exploration of slow motion. In amongst the examples of cheetahs running very, very fast, slowed down to very, very slow, on the Internet we can find some screendance artists who have been inspired by the very same technological possibilities and apply the techniques and related concepts to their work.

Sabroso is the work of The Performing Kitchen, a collaborative platform for research and creation on dance and performance, coordinated by Marcos Moraes. Utilizing the razor-sharp images of high definition and played out entirely in slow motion, here is a narrative involving a collection of individuals who appear to have gathered to create a celebration feast. According to the collective’s own publicity material, available on their website, the concept behind the work is part inspired by the activities of Gordon Matta-Clark and his cohorts in 1970s, whose New York café, called Food was an artistic gesture. However, with its richness of tone, the colorful performed scenario and filmed against a black background, Sabroso is also reminiscent of Dutch still life painting from the 1600s and the films of Peter Greenaway come to mind too. In Sabroso, the scene is rich, the actions simple and the extreme slow motion serves to amplify the emotion inherent in the fragments of action that we see, whether that is a gesture, a look or a physical intervention.

Film Still. Sabroso. Dir. Osmar Zampieri. Chor. Marcos Moraes. Comp. Aricia Mess. Perf. The Performing Kitchen. 2015. HDV. Image courtesy of the artists.

Also filmed in high definition, and slowed right down, in SAMBA #2 (password: samba) the collaborative team chameckilerner (choreographers and filmmakers Rosane Chamecki and Andrea Lerner) present a single silent shot that frames the hips of a female samba dancer. As the artists themselves point out, this is a copy of a shot frequently used in the filming of samba for Brazilian television and, by presenting it in this heightened way, they encourage a rare scrutiny of the image.

The close up view of the woman's hips as she twists and turns, with scant jeweled underwear barely concealing her sex, might hardly register in the flow of images of the televised dancing spectacular. But here, the artists invite us to question our reaction to the image. On watching, fascination turns to disbelief and then self-scrutiny as the dancing flesh behaves in unfamiliar, uncomfortable ways.

Film still sequence. SAMBA #2. Dir. and Chor. chameckilerner (Rosane Chamecki & Andrea Lerner). 2014. Images courtesy of the artists.

Rewind 25 years and screendance artists were using comparable techniques to enhance the impact of filmed dance movement. L'Entreinte is the ultimate romantic screendance love duet in which the physical interaction between the couple is played out in slow motion. Made in 1988 by the influential and innovative French choreographers Joelle Bouvier and Regis Obadia, this exquisite dance film is one of three films that they made around that time with their company L'Esquisse.

Whereas Sabroso and Samba # 2 communicate through crystal clear high definition, here the images have been captured on film, probably 16 mm, and in monochrome. The image is blurred and opaque, and this painterly quality is enhanced by the slow motion, each element adding to the timelessness of the scene. A man and a woman, dressed in evening clothes, are in a space, which is empty apart from a bed. The couple is in the throes of a passionate relationship. We cannot know if this is the beginning or the end, desire or rejection, as they repeatedly fall together, pull apart, break free and run, one grasping, the other pushing away, then roles reversing. Initially, the music is of romantic strings, then the booming sound of the slow motion movement fades in, emphasizing the intense physicality of the slowed dance.

Screenshot. L'Entreinte. Dir. and Chor. Joelle Bouvier & Regis Obadia. Comp. A. Vivaldi. Perf. Bernadette Doneux & Eric Affergan/L'Esquisse. 1988. 16mm.

Also presented in monochrome and featuring a couple repeatedly falling and getting up again, Montreal screendance dance artists Priscilla Guy and Catherine Lavoie Marcus's Singeries presents a refreshingly simple concept that is packed with knowing. Two women stand opposite each other in a neutral space. They are wearing professional, everyday office clothes and they appear to be interacting, when suddenly they fall to the ground, as though shot, or felled, or simply unable to stand any more. The image cuts to the women standing again, then they fall again and so begins a series of rhythmic, repetitive edits, the choreographic structure of the work enhanced by the use of the echoing synch sound. The neutral gaze of the camera as witness to the quotidian movement brings to mind the Yvonne Rainer films, whereas the filmic treatment of monochrome and the use of slowed down sound recall L'Entreinte. In this short excerpt here, Guy and Marcus offer a contemporary reflection of female relationship and failing to remain upright in the world.

Film still. Singeries. Dir., Chor., and Perf. Priscilla Guy & Catherine Lavoie Marcus. 2015. Image courtesy of the artists.

Another recent discovery for me is the work of US/German performance artist and filmmaker Julia Metzger-Traber, who, like many independent screendance artists, makes her work available online. For example, her poetic dance documentary film Rhizophora, which features the startling and moving improvised movement performance by young residents of the Friendship Village in Vietnam, who are living with disabilities caused by their grandparents' exposure to the deadly Agent Orange.

Screenshot. Rhizophora. Dir. and Chor. Julia Metzger-Traber & Davide De Lillis. Comp. Barnaby Tree. Perf. Residents of the Friendship Village, Vietnam. 2015. Video.

In another of Metzger-Traber's short films viewable on the Internet, Die Weiten Wege, the simple and playful narrative which follows a pair of fingers as they walk through a world of close up textures and micro environments becomes a meditation on body image. Our acceptance of index and middle finger as the inquisitive legs of a ‘hand-person’ questions assumptions about the type of body we expect, or perhaps are comfortable seeing on screen, as did the lens of Rhizophora.

Screenshot. Die Wieten Wege. Dir. and Chor. Julia Metzger-Traber. Comp. Fourtet. 2014.

Films like those made by Julia Metzger-Traber, Priscilla Guy, and chameckilerner are evidence that the art form continues to be in good hands. Amongst others, these artists show that the form can be political, personal, inclusive, disturbing, generous, and beautiful. Moreover, these artists are using the Internet to disseminate their work, no longer dependent on the preferences of a broadcaster or distributer, nor even the festival programmer, as was the case not much more than a decade ago.

There are many stories waiting to be told and screendance continues to offer the potential to communicate across verbal language barriers, to an increasingly visually literate world, with thoughtfulness and integrity. The Internet provides an invaluable platform on which to share this work with as wide an audience as possible. As we have seen even within the framework of this article, there already exists a rich and varied program of screendance available online. However, despite its obvious rewards, an increasing reliance on the Internet as a platform for viewing work can also be fraught with problems. For example:

You do need good access to the Internet, which is certainly not a given in many parts of the world. In order to watch material for this article, I had to drive back and forth a number of times between where I live (with slow broadband) and a local café (with a super fast connection).

Watching work online does not necessarily provide the rich visual and acoustic experience that the artists might plan for, nor the shared engagement of a theatrical screening that public events can offer. The curating of festival programs remains in constant need of attention to bring it up to the level of expectation we have for the art form and a similar urgent requirement exists for the internet, to assist the online audience’s navigation through—and understanding of—the ever-expanding catalogue of work available on the Internet.

Bound up with this is the notion of free access on the Internet, and of course this impacts an artist's ability to forge a sustainable life. Although there are systems in place for 'pay-to-view' screendance, most work is made available without charge and, as an audience, we have come to expect that we can watch work for no payment. While much is made of the increasing accessibility of technology, no material or time is without cost, and presumably this affects who has the means to make and distribute work, while also being able to earn a living.

It is a dilemma that has long existed: as makers we want our work to be seen and yet rarely receive payment for screenings or viewings, whether that be in a curated show, a festival, or now online. Moreover, as artists and producers, we may feel uncomfortable with putting in place the obstacle of online pay-per-view which may deter the curious Internet explorer. It is beyond the scope of this article to unpack the issues of arts funding, other than perhaps to make an observation that the international screendance community does seem to be made up of a particularly committed and generous group of people, for whom making work and sharing it, along with the knowledge that surrounds it, is central to engagement with the art form.

The ability to distribute work on the Internet supports a belief that what can be expressed through dance and the moving image is important and should be shared. Although sometimes at significant personal cost, those that sense its value look for ways in which to sustain a life and make work, and to create related activities, that demand a commitment that goes well beyond monetary compensation.

Furthermore, in some ranks the screendance community is becoming increasingly aware of the need to develop and articulate a pedagogy for the art form and part of this is the realisation that, as artists, teachers and scholars working in the field, we must be well-versed in our chosen art form, both past and present. There is a continuing need to identify and share the existing and evolving works that speak to an understanding of screendance and increasingly the Internet plays a role here. The exercise of curating the growing list of works—both historic and contemporary—that are available to view online is central to this and will provide a rich seam of knowledge, essential for the continued healthy development of the art form.

Biography

Katrina McPherson is an award-winning filmmaker and screendance artist, whose creative, academic, and educational work is at the forefront of the international field. She is the sole author of the workbook Making Video Dance (Routledge, 2006) and has taught dance film and related subjects all over the world. Most recently, Katrina has devised and presented the Symposium for Teachers of Screendance with Douglas Rosenberg at the American Dance Festival in North Carolina and at the Dance on Camera Festival in New York, USA.

Email:

Website: www.makingvideodance.com

References

10 Men. Dir. Graham Clayton-Chance. Chor. Nigel Charnock. Perf. The Nigel Charnock Company. 2012. https://vimeo.com/36006586

30 Second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists – Nam June Paik. Dir. Joan Logue. Perf. Nam June Paik. 1982-83. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGnDrJu-Xf4

30 Second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists – Steve Reich. Dir. Joan Logue. Perf. Steve Reich. 1982-83. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JE2tGJyQEeo

30 Second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists – Laurie Anderson Dir. Joan Logue. Perf. Laurie Anderson. 1982-83. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qt_zQbu3dFA

30 Second Spots: TV Commercials for Artists – John Cage Dir. Joan Logue. Perf. John Cage. 1982-83. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXAHrinbDNg

Bridges Go Round. Dir. Shirley Clarke. Comp. Teo Macero/ Louis & Bebe Barron. 1958. 16 mm. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2gxX74iGRTc

Hand Movie. Chor. Yvonne Rainer. Cinamatogr. William Davis. 1966. 16mm. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CuArqL7r1WQ

L'Entreinte. Dir. and Chor. Joelle Bouvier & Regis Obadia. Comp. A. Vivaldi. Perf. Bernadette Doneux & Eric Affergan/L’Esquisse. 1988. 16mm. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XqwWk-PmxG0

Rhizophora. Dir. and Chor. Julia Metzger-Traber & Davide De Lillis. Comp. Barnaby Tree. Perf. Residents of the Friendship Village, Vietnam. 2015. Video. http://www.cheneso.com/Rhizophora (trailer) https://vimeo.com/123498557 (excerpt)

Roseland. Dir. Walter Verdin & Wim Vandekeybus Chor. Wim Vandekeybus Comp. Thierry de Mey and Peter Vermeersch Perf. Ultima Vez. 1990

Sabroso. Dir. Osmar Zampieri. Chor. Marcos Moraes. Comp. Aricia Mess. Perf. The Performing Kitchen. 2015. HDV. http://www.acozinhaperformatica.com/#!sabroso/kmctd

SAMBA #2. Dir. and Chor. chameckilerner (Rosane Chamecki & Andrea Lerner). 2014. https://vimeo.com/119779106. pw: samba

Singeries. Dir., Chor., and Perf. Priscilla Guy & Catherine Lavoie Marcus. 2015. https://vimeo.com/146858193

Trio A. Chor. and Perf. Yvonne Rainer. Cinematogr. Robert Alexander Prod. Sally Banes. 1978. 16mm. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZwj1NMEE-8

Die Wieten Wege. Dir. and Chor. Julia Metzger-Traber. Comp. Fourtet. 2014. https://vimeo.com/114092307

Notes

Douglas Rosenberg in a group email communication dated 12/26/15.↩