Intimate Encounters: Screendance and Surveillance

John White, University of Edinburgh

Abstract

This article explores some ways in which screendance might invite a greater or deeper degree of kinesthetic empathy than is traditionally possible with live performance. In particular, the use of the close-up and the creation of editing rhythms are two strategies that extend screendance viewers' kinesthetic empathy into a more intimate relationship with the dance(rs). Furthermore, this article analyzes Katrina McPherson's screendance The Truth as a case study in which this intimate viewing relationship is characterized by a kind of voyeurism shared with the act of viewing surveillance. I draw on some surveillance theory and artist Jill Magid's piece Evidence Locker in order to explore the surveillance aspects of The Truth.

Keywords: screendance, surveillance, kinesthetic empathy, voyeurism

In this writing I argue that the use of surveillance-style footage in Katrina McPherson's screendance The Truth reveals how a certain voyeurism characterizes viewing patterns of screendance more generally. Specifically, I argue that screendance's camera and editing techniques bring viewers into a more intimate spectator relationship than is possible when viewing live performance and that these techniques simultaneously position viewers as voyeurs. The camera in screendance makes possible for viewers a space of intimacy in which, like with surveillance and surveillance-style footage, it conveys intimate information about the dance(rs) through images that appeal to the viewers' imaginations. Intimacy as I mean it here operates on two levels: the (sense of) proximity between spectator and dance(r) often enabled by the camera, and the deeper empathic relationship that I focus on in this article.

My use of the term "intimacy" is largely tied up with the much-theorized concept of kinesthetic empathy, which describes how spectators viewing human movements do not simply watch but also feel them in their bodies and minds.1 In Susan Leigh Foster's words, "The viewer, watching a dance, is literally dancing along."2 While kinesthetic empathy has been analyzed extensively in dance and film, there are fewer instances of critical or scholarly work devoted to understanding kinesthetic empathy in dance that is made for the camera.3 I will look at how the camera extends notions of kinesthetic empathy as it pertains to live dance by virtue of the camera's ability to bring viewers into the space of the dance(rs), to focus viewers' attention on specific body parts and sounds, and to encourage a potentially deep empathic connection between viewer and performer that is inflected with the voyeuristic dimensions of contemporary surveillance. I choose the word intimacy because these forms of relating, by way of the camera, to the bodies in screendance go beyond kinesthetic empathy. As I will discuss later, kinesthetic empathy more typically refers to an affective, embodied response, particularly with regards to live performance. Intimacy as I mean it refers to a range of responses that are more cognitive and abstract, but nonetheless oftentimes embodied.

First, I will summarize some of screendance's techniques—about which McPherson and other scholars have written—to establish the intimate form of spectatorial access that is made possible in screendance by the movement of the camera and its proximity to dancers' bodies, as well as by editing rhythms.4 Second, I will look at three scenes in The Truth to demonstrate how the surveillance-style footage interspersed throughout the work reveals the ways in which screendance more generally acts as its own form of surveillance that hooks viewers by offering voyeuristic glimpses of close-up details of the dance(rs). Last, I will discuss the artwork Evidence Locker by Jill Magid to show how surveillance space can enact and even encourage an emotional connection between the viewer and the viewed. It is this sense of connection that, on top of the physical intimacy enabled by the camera, takes viewers of much screendance work, not just of The Truth, into the realm of emotional intimacy with the performers. In my experience of watching screendance it is this intimacy via the close-up camera that makes the act of viewing much screendance work so compelling. Drawing on the work of Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason, screendance scholar Karen Wood writes that "kinesthetic response may be the foundation to spectators' motivations for watching dance and the pleasure gained from the experience."5 I would extend this statement further to propose that the intimate kinesthetic response heightened by the camera may be the foundation to some spectators' motivations for watching screendance.

The Choreographed Camera

In this section I focus on how the choreographed camera as a mediating mechanism between viewer and performer complicates and extends notions of kinesthetic empathy as they have been theorized in relation to watching live dance.6 McPherson has written extensively about how she and other screendance practitioners manipulate the capabilities of the camera as a means of drawing viewers into their work.7 Two methods that I will look at here in relation to The Truth are the ability of the close-up to bring viewers into the dancers' kinesthetic spaces and the careful creation of editing rhythms that permit viewers themselves to feel both the dancers' movements and the screendance creators' responses to those same movements.

Foster, in tracing the origins of kinesthetic empathy as a term, writes that empathy "has been variously conceptualized in relation to physical experience."8 Indeed, Reynolds writes that kinesthetic empathy is best understood in terms of affect rather than emotion.9 She describes affect as embodied, as "a stage where emotions are still in the process of forming," and as "that point at which the body is activated, 'excited,' in the process of responding."10 She further distinguishes affect and historical concepts of empathy that emphasized dynamism and inner movement from the cognitive dimensions of emotion.11 Both Foster and Reynolds, however, analyze kinesthetic empathy exclusively in relation to live performance. For example, Reynolds writes about how, as viewers, we can often be "uncertain where to focus our gaze" when watching dance.12 Do we follow an individual or the movements of the overall group of dancers?

With screendance's (sometimes very liberal) use of the close-up, options for where viewers focus their gaze within the larger dance—and on the dancers' bodies—are narrowed significantly. For example, in one scene of The Truth the camera pans slowly down a dancer's suspended arm as she lets the force of gravity move it in slow circles. In another scene, the camera zeroes in on the slight shaking of a tensed, outstretched hand—a tiny, not even necessarily choreographed movement detail that would not be as readily visible to a spectator in a conventional theater. According to Marcia B. Siegel, early versions of televised dance recordings typically used wide, static shots as a means of "simulating the audience's view of dance in the theater" (she writes that close-ups were seen as "treacherous").13 However, McPherson argues that the strength of screendance lies in harnessing the capabilities of the camera, such as using it to get up close. Specifically, McPherson has explained how the choreographed camera can "enter the dancers' kinespheres—the personal space around them that moves with them as they dance—focusing on a detail of movement and allowing an intimacy that would be unattainable in a live performance context" (my emphasis).14 In this scenario, the dancer and the camera act as "mutual performers," a relationship in which the mediums of dance and film do not serve or impede but rather complement one another.15

In her book Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image, Erin Brannigan devotes an entire chapter to the close-up. Brannigan looks to the writings of Béla Balázs and Gilles Deleuze to show the ways in which the close-up in cinema has been theorized largely in relation to the face. According to Deleuze, "it is the face, with its relative immobility and its receptive organs, which brings to light … movements of expression while they remain most frequently buried in the rest of the body."16 But Brannigan argues that "[d]ance involves a bodily expressivity that attributes to the body what is usually given to the face: expression, intensity, feeling,"17 and she points to the work of postmodern choreographer Trisha Brown for an example of the "non-hierarchical dancing body"18 that choreographically gives equal weight and importance to all body parts and all kinds of movement.

McPherson and editor Simon Fildes give equal visual weight and importance to various body parts in The Truth. McPherson's directing and Fildes' editing do not preference any single area of—or approach to—the dancers' bodies. In fact, the dancers' faces are often cropped out of the frames entirely. Instead, The Truth shows an interest in the "smaller detailed movements of the body and its parts," such as the aforementioned shaking hand, that Brannigan terms "decentralized micro-choreographies."19 By frequently showing the moving bodies in The Truth as torsos, legs, etc. isolated from the other body parts that initiate or carry a corresponding aspect of the movement, McPherson and Fildes focus viewers' attention on the ways in which specific physical sites commence, continue, or complete micro-movements of the choreography. They draw viewers in close to the expressive qualities of an encircling arm, a swiveling pelvis, or a sharp intake of breath. The Truth invites viewers to attribute to a close-up shot of a shaking hand what they might usually project onto the face: an expression of strain, a feeling of nervousness. By such strategies, screendance and its intervention of the camera encourage a more affective and close form of kinesthetic empathy with individual dancers. Though she does not write particularly about the close-up, Wood agrees that "[w]atching film can allow the spectator to look more closely at the movement, permitting a more detailed and intimate gaze at the action on the screen and therefore engaging with emotional expression."20

It is not just strategies during recording that can deepen viewers' kinesthetic empathy with the screendance, but also rhythms and textures achieved during the editing process. McPherson includes a chapter in her instructional book Making Video Dance on "The Choreography of the Edit," or post-production strategies that continue and compound the effects of the choreographed camera. McPherson suggests that individuals making screendance cut from one clip to another before the movement is completed so that "the viewer will finish off the movement in their mind's eye."21 Relatedly, Foster writes of Ivar Hagendoorn's argument that viewers of a live dance performance "do not simply decide where or what to watch, but instead, create versions of the dance as it unfolds in time before them."22 Viewers "think up the movement and decide how and where the dancer should move next," like the choreographer before them has done.23 The fact that McPherson suggests specifically exploiting this tendency in viewers and inviting them to imaginatively complete the depicted movement, rather than showing them its completion, as a technique of screendance demonstrates an intention to strategically engage and intrigue viewers by appealing to more cognitive responses.

Screendance theoretician Karen Pearlman writes how editors of all films, not just dance films, have an embodied reaction to the material they edit. In addition to kinesthetic empathy—which she describes as "feeling with movement" (original emphasis)—she uses in her analysis the term "corporeal imagination," by which "the body … imagines in relation to its own experience, drawing on remembered sensations to recognize feeling in movement."24 According to Pearlman, when looking at filmed material, editors do not just notice when a performer blinks or breathes but also imitate it. The editor "[draws] on their own experiences of the rhythms of, for example, blinking" and in this way "uses their … kinesthetic empathy to relay the external rhythms, which they perceive in the developing edits, through their internal rhythms, to create the rhythm of the film" (original emphasis).25 Wood, though she does not draw on Pearlman, writes that for viewers in turn "[e]mbodied engagement and kinesthetic response is therefore affected by … participation in a rhythm external to that of our own body, which in this case is the rhythm of a film."26

Screendance practitioners engage viewers in an embodied response to their work that is made that much more powerful by the fact that the work is imbued with its creators' own embodied responses. Pearlman writes that kinesthetic empathy happens for viewers of films as well as for viewers of live performance, but "[t]he difference is that, in cinema, the actor's breath rhythms have passed through the hands, or perhaps the lungs, of the editor."27 The same goes for The Truth – its dancers' breaths and movements and the bodies of McPherson and Fildes. It is easy to imagine that, rather than randomly ordering the clips that make up The Truth or editing it in a manner that maintains its original continuity, McPherson and Fildes instead edited the screendance by playing off of their own kinesthetic associations with various potential sequences of clips in order to ensure a greater likelihood that viewers feel kinesthetic empathy with the resulting work.

In The Truth McPherson often repeats the same clip several times, even back-to-back with itself. While such repetition can produce a wide variety of responses in viewers, such as even causing them to lose interest, it is possible that the repetition produces or strengthens kinesthetic empathy for viewers. McPherson and Fildes also overlay clips with sound that is different from the clips' original sync sound so that, for example, the sound of a particularly compelling exhalation may coincide with a release in a dancer's movement, thereby (artificially) heightening the drama of the mo(ve)ment. Coupled with the camera's ability to bring the viewer right up into the movement and the breath, these editing strategies have the potential to draw in the viewer more powerfully than in live choreography typically seen from further away. Pearlman's proposition that viewers' empathic responses to a screendance may be conditioned, even to some degree prescribed, by the empathic responses of the work's editors complicates Foster and Reynolds' concepts of kinesthetic empathy.28 Whereas with Reynolds' kinesthetic empathy viewers of live dance have an affective response in which "the body is … in the process of responding" and "emotions are still in the process of forming,"29 viewers of screendance, by way of the editors' already-played-out kinesthetic responses to the material, may in the moment of watching engage on a deeper emotional level. Such instantaneous responses are difficult to assess or measure; however, in my own experience of watching screendance I have felt my sense of amusement, sympathy, or joy in response to a movement or my sense of connection to, even desire for, a dancer heightened by camera techniques.

A Voyeur's Window

The Truth intersperses dance scenes with surveillance-style footage taken in a public station. Seen side-by-side with the surveillance-style footage, the dance scenes function effectively as a kind of surveillance through which viewers voyeuristically observe the dance(rs). I have drawn my understanding of voyeurism largely from scholar Clay Calvert's concept of "mediated voyeurism" that he argues dominates contemporary culture and that he defines (in short) as "the consumption of revealing images of and information about others' apparently real and unguarded lives … frequently at the expense of privacy and discourse" (my emphasis).30 In The Truth, viewers consume revealing images of and information about performers, not unsuspecting people going about their everyday lives. However, the screendance manipulates the aesthetics of surveillance as a means of setting up viewers to feel as though they are watching unsuspecting, anonymous people. It is for this reason that I will here apply surveillance theory to a work that does not make use of actual surveillance but nonetheless positions viewers to relate to its subjects within surveillance space.

The project was framed from its outset as an investigation into how, according to Fildes, the truth of a situation is dependent on the context in which someone is given visual information, or how the truth of any situation is nebulous, changing, and subjective.31 The screendance opens with a first clip of surveillance-style footage. The camera is positioned above the station crowd and is stationary. The footage is grainy and is time- and date-stamped in the top left corner.

Screenshot. The Truth

There is no sound from the station. After anonymous members of the crowd are surveilled for a while, the camera singles out the work's four performers—Karin Fisher-Potisk, Kate Gowar, Matthew Morris, and Robert Tannion—walking through the station. One minute into the work, the footage changes from a frozen, zoomed-in shot of one of the men (Tannion) after he has placed a coffee cup on the ground to higher-quality, non-surveillance-style video of him with the same clothing repeating the action. This time he carries out the action in a closed-off, white-walled room where he is alone.

The surveillance aspect of The Truth was envisioned specifically with CCTV (closed-circuit television) in mind. Robert Knifton writes that there is a greater proportion of surveillance cameras to population in the UK than anywhere else in the world and that the UK accounts for one-fifth of the global CCTV market.32 Statements like David Lyon's that "to participate in modern society is to be under electronic surveillance"33 are therefore important to a project conceived and sited in the UK. Surveillance is so widespread that John McGrath has argued that it is "turning the whole of life into a public performance," that it "puts life on show."34

As viewers of The Truth come to know the people in the initial zoomed-in, frozen shots as dancers, subsequent surveillance footage thereby suggests not only that their movements in the station are choreographed but also that the movements and behavior in which we all engage in public, surveilled space is, whether or not we are conscious of it, choreographed by those who are watching. This no longer includes just bystanders whose gaze we may think we feel on us but, more importantly, city planners, governmental bodies, and intelligence agencies. In Knifton's words, "CCTV is a key aspect in the … re-imaging of our cities since it allows those with social control to define what is ordinary behavior and to spatially express this normativity through the asymmetry of power the cameras give them."35 Using the city of Liverpool as a case study, Knifton gives surveillance in the criminalization of the homeless and skateboarders as examples of this "spatial cleansing" and "defining [of] acceptable bodily conduct in public."36

In Hard Core, her seminal study of pornography, Linda Williams writes that cinema normalized so-called perversions like fetishism and voyeurism as "technological and social 'ways of seeing.'"37 She writes that, "[a]s a result, viewers gradually came to expect that seeing human bodies in motion in the better way afforded by cinema [as opposed to the naked eye] would include these perverse pleasures as a matter of course."38 Relatedly, Maciej Ożóg writes that surveillance is so prevalent today that "voyeurism and exhibitionism are not only justified … but they also become desirable and normal, not to say necessary forms of behavior in the mass media society."39 While neither of these quotes deals directly with screendance, they speak to the degree to which voyeurism is so often encoded in many peoples' relationships to images of moving bodies (sometimes problematically). The mere reproducibility and familiarity of the style of surveillance footage that permit the station scenes in The Truth to be read as such show how commonly the visuals of surveillance and voyeurism proliferate in our day-to-day lives, whether it be in the form of peeking into celebrities' lives via reality television, watching police footage on the news, or seeing one's self appear on the CCTV screen in a gas station or corner store. While this makes the pseudo-surveillance images in The Truth not unusual in and of themselves, the fact that the images are constructed to appear as surveillance affects how the work is perceived. Specifically, the 'surveillance' in The Truth engenders a voyeuristic intimacy between viewers and dance(rs) that characterizes the act of viewing the whole work, not just the surveillance-style scenes.

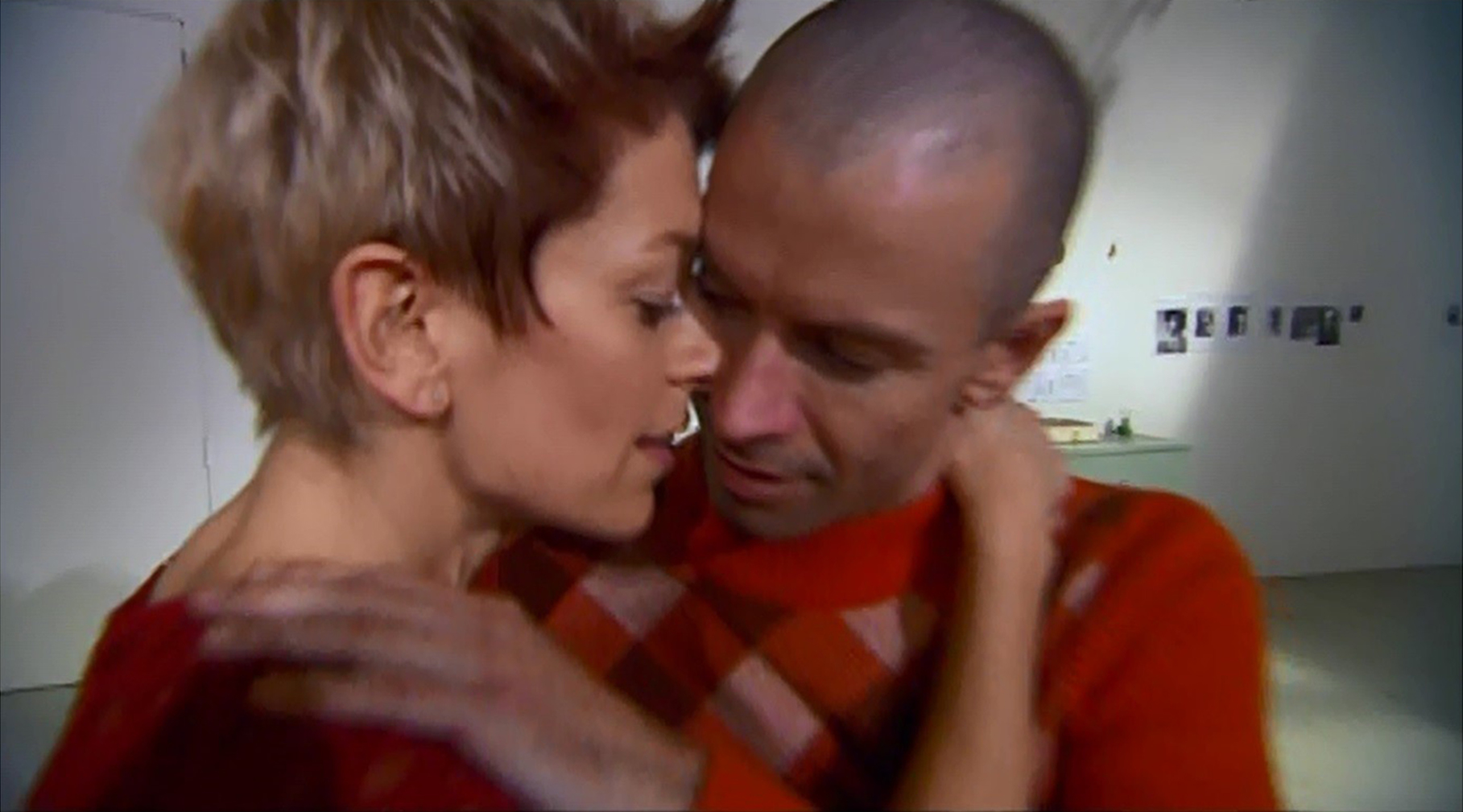

An important aspect of this voyeuristic intimacy in The Truth has to do with the work's blurring of private and public space. Lyon writes that "today [privacy] is tightly tied to avoiding surveillance."40 Whenever The Truth switches to non-surveillance recordings, the higher quality, rhythmic editing, and movement capabilities of the choreographed camera that differentiate it from the surveillance camera and create a sense of spectatorial intimacy are compounded by the spatial move from the Liverpool Street Station to the more private-seeming rooms in which the dancers dance. Not only do the white-walled spaces (in their emptiness and closed-off seclusion) suggest the viewer is receiving a degree of exclusive access, but so does the choreography performed in those spaces. No longer being observed in the very public station, the dancers move more freely and uninhibited. They also move in ways that retroactively detail their relationships as observed in the station. A surveillance-style scene shows one of the women (Fisher-Potisk) walking together and acting familiarly with one of the men (Morris) as though he is a travel partner or friend. Then, in the scene that follows (the first in which all four dancers dance together), the two hold each other closely.

Screenshot. Karin Fisher-Potisk and Matthew Morris performing in The Truth

The embrace marks a move towards increased physical intimacy between the performers, and I notice while watching that I in turn feel closer to them. Whereas Morris and Fisher-Potisk laugh and share a parting hug in the station, they now reveal a perhaps more amorous dimension to their relationship. Later in the work Fisher-Potisk takes off her shirt so that she is in just a bra, and the man with whom she dances (now Tannion) takes off his trousers. They hold each other closely, as do the other two dancers (who have also taken off their trousers). This is another suggestion that the space is a private one, one in which couples can feel more open to express human intimacy.41

Though these quiet moments between men and women align in a very traditional, heteronormative sense with Lyon's statement that "the private has usually been associated with the domestic,"42 they represent a set of behaviors (public displays of affection) that many people today increasingly feel free to carry out in very much non-private places.43 More importantly, the white-walled spaces featured in the non-surveillance-style video are actually public. The scenes were filmed in an extension of Victoria Miro Gallery in London and a factory-turned-artists'-space in Dalston, a district in northeast London.44 They are locations that are heavily surveilled or are indicative of, in the case of the former, institutions that monitor people visiting their exhibitions and, in the case of the latter, workplaces that record the comings and goings of visitors.

The 'non-surveillance' scenes are sited in buildings that (even to viewers unaware of the real identities of the locations) suggest by their white walls their moneyed, high-security status. Therefore, although transitions from surveillance-style footage to non-surveillance-style footage indicate a move from public to privatized space, the whole screendance constitutes a kind of surveillance. Early in the work, the initial station images and the subsequent video of Tannion dancing alone in a room are seen playing on a small, blueish screen behind Morris as he dances in the scene that follows.

Screenshot. Matthew Morris performing in The Truth

This video-within-the-video enables "viewing through to other times and spaces," 45 but it also shows the viewer that the surveillance- and non-surveillance-style video are ultimately more or less the same.They both function as records of what McPherson and company did in the spaces they received permission to use, and they both allow viewers to watch closely the work's protagonists.

The non-surveillance-style images are more successful as observational material in that they transmit more information about the people they track than does the station footage. According to McGrath, "the surveillance camera displays the limits of its relation to the real place it is recording" in terms of, among other things, its typically low image quality and lack of sound.46 However, McPherson's choreographed camera takes viewers who have just seen fuzzy, confusing surveillance-style video of the subjects of The Truth immediately into those subjects' intimate kinesthetic space to know their bodies, their movement styles, their sounds, and the way they look at and respond to each other in a manner that is not possible with the surveillance technology the work imitates. When McPherson repeats several times a close-up clip of Morris and Fisher-Potisk holding each other and swaying, she not only conditions viewers' kinesthetic responses to the clip but also invites viewers to detail their evolving sense of the relationship between the two dancers and, in turn, their relationship to the dancers. Each time that I have watched The Truth, I have felt reeled in by the increasingly intimate information I was fed until I ultimately felt unable to look away, even as I wondered if I should be watching something that felt quite private.

It is apt, then, that Jeffrey Bush and Peter Z. Grossman have called the screen in screendance, much like in surveillance, "a one-way mirror, a voyeur's window."47 The Truth foregrounds the ways in which screendance gives us a window into the intimate details of others' bodies and lives—even details that may initially seem as uneventful as the micro-details (e.g. the shaking hand) that I discussed in the previous section. McPherson and Fildes seem to have edited The Truth to create patterns, rhythms, and textures that invite us to investigate these details and our responses to them within a kind of mediated voyeurism.

Intimate Choreographies

Foster expresses skepticism about the possibility of empathetic connection in the "culture of surveillance."48 In reference to a 2006 piece by Philadelphia's Headlong Dance Theater titled Cell, in which participants were led by a dispatcher (via a cell phone) through various interactions all around Philadelphia, Foster writes that the technology used imposes a sort of distancing that ultimately lends the impression that "the piece is being impersonally managed."49 Jill Magid's 2004 work Evidence Locker speaks to the contrary, that surveillance space can actually engender a deep emotional intimacy across the screen that subverts the technology's detached, uneven power structure. Evidence Locker is a fitting companion piece to The Truth's manipulation of surveillance technology and Cell's participatory dimensions.

Magid lived for 31 days in Liverpool creating a commissioned work for the Liverpool Biennial. At the time, Liverpool had, according to Magid, the largest CCTV surveillance system in the world.50 Magid spent her time in the city writing and submitting daily Subject Access Request Forms detailing her activities and appearance so that footage of her would legally have to be kept in an evidence locker for each of the 31 days, which is the amount of time after which all un-requested surveillance recordings cascade off the system. At the end of her project, the footage was made available to her, and she has since, in turn, made it available online to the public for perpetuity.51 She chose to fill out the daily forms, which she has made available alongside the footage, as though they were love letters addressed to her Observer:

Dear Observer,

I don't want to introduce you to everyone. I don't want to share you. I separate you and you separate me.52

Her letters highlight the voyeuristic dimensions of surveillance—for example, on day two: "There are no curtains and I can imagine it's not so difficult to look into this room from the outside. I know you are not supposed to do that, but I bet you sometimes do it anyway."53 Although the letters received no official written response, the officers manning the CCTV control room became increasingly invested in the poetics of the relationship Magid was setting up, especially in the case of one officer who, as told in Magid's final letter, gives her a ride on his motorcycle out beyond the range of the city's surveillance on her last day. That Magid then opened the footage and her letters up to outsiders underscores her interest in both voyeurism and exhibitionism in that she, in turn, invites the public at large to live vicariously through the intrigue of the story and the searching cameras.

Beyond voyeurism, though, Evidence Locker makes visible the intimate choreographies that observers create for those they observe, or even vice-versa. In the climax, so to speak, of the piece on day 24, Magid closes her eyes while on a busy public walkway, and an officer in the control room directs her movement via a phone and earpiece—in a manner not unlike Cell—as he watches her and moves and focuses the cameras in relation to her.

Screenshot. Jill Magid performing in Evidence Locker

In the accompanying Subject Access Request Form for the day Magid writes, "I imagined myself as you saw me and let my hands drop to my sides. I felt your approach. You stopped speaking. I could feel when my face filled your window … And we rested like that, for maybe a minute."54 On the other side of the interaction, as Knifton writes, "the observer performs the role of jealous lover" in that the surveillance controllers went beyond a willingness to partake in Magid's game and began to devote time to looking for her, helping her, and speaking to her both on and off the clock.55 Towards the end of the project Magid concludes, "I did not critique your system; I made love to it. You blushed."56

Evidence Locker perfectly exemplifies McGrath's statement that "the multiple desires and identifications that arise within surveillance space can sometimes coalesce into feelings of love."57 If we accept that "the surveillance matrix creates not simply a parade of representations, but a lived space in which we experience our bodies and their relationships differently from previously," he argues, then "we inevitably accept that the emotions and needs intrinsic to human life will likewise be reconfigured in this new space."58 Though I do not mean to suggest that viewers of The Truth necessarily fall in love with any of its performers, the use of pseudo-surveillance in the screendance foregrounds the reconfiguring of human emotions and needs that takes place when viewers are given the sort of intimate spectator-voyeur position that The Truth specifically and the choreographed camera more generally can provide.

Screenshot. Matthew Morris and Robert Tannion performing in The Truth

The associations between the dancers that evolve over the course of The Truth involve the viewer in a triangulated relationship with the dancers, mediated by the camera, that does not differ that much from the love affair in Evidence Locker. Of course, viewers of screendance works do not usually have the contact or control that the officers had with or over Magid. However, screendance is nevertheless crafted in a manner that prioritizes viewers' sensations and experience and that draws them affectively and emotionally into the movements and relationships. Among other methods, viewers are drawn in through the use of the close-up and through editing rhythms that play off of the editors' own kinesthetic responses to the movements and relationships. These methods can also produce embodied responses in viewers. With The Truth, this might most readily occur the several times that dancers purposefully and significantly lock eyes with the camera, sometimes for as long as four or five seconds amidst movement and editing that is otherwise rapidly changing. Under the performers' close-up, direct, and prolonged (and oftentimes repeated) gazes, the viewer-voyeur feels caught, considered, connected, and maybe even blushes.

Biography

John White is an art historian, dancer, and writer. He received a BA in History of Art and Architecture from Brown University, where he was a member of Brown's modern dance repertory company. He also received an MSc in Modern and Contemporary Art: History, Curating, and Criticism from the University of Edinburgh. He has worked at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas and currently lives and dances in New York City.

Email:

References

Bell, David. "Surveillance is Sexy." Surveillance and Society 6.3 (2009): 203-212.

Brannigan, Erin. Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195367232.001.0001

Bush, Jeffrey and Peter Z. Grossman. "Videodance." Dance Scope (Spring/Summer 1975): 11-17.

Calvert, Clay. Voyeur Nation: Media, Privacy and Peering in Modern Culture. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2000.

Cell. Headlong Dance Theater. Philadelphia: 2006. Performance.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

"Embedded – Jill Magid" (2011). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQE2zW8yUWI

Evidence Locker. Dir. Jill Magid. Liverpool: 2004. Performance, digital video.

Foster, Susan Leigh. Choreographing Empathy: Kinesthesia in Performance. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Friedland, Sarah. "The Meaning of the Moves: Gestural Mythologies and the Generic Film." International Journal of Screendance 6 (2016): 39-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v6i0.4940

Knifton, Robert. "You'll Never Walk Alone: CCTV in Two Liverpool Art Projects." In Outi Remes and Pam Skelton (Eds.) Conspiracy Dwellings: Surveillance in Contemporary Art. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2010. 83-94.

Lyon, David. The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994.

Magid, Jill. Evidence Locker. http://evidencelocker.net/story.php.

----. One Cycle of Memory in the City of L. Self-published, 2004.

McGrath, John E. Loving Big Brother: Performance, Privacy and Surveillance Space. London: Routledge, 2004.

McPherson, Katrina. "A Passion for Screen Dance." Dance Theatre Journal 13.4 (1997): 48-50.

----. Making Video Dance: A step-by-step guide to creating dance for the screen. London: Routledge, 2006.

Ożóg, Maciej. "Surveilling the Surveillance Society: The Case of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer's Installations." In Outi Remes and Pam Skelton (Eds.) Conspiracy Dwellings: Surveillance in Contemporary Art. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2010. 95-112.

Pearlman, Karen. Cutting Rhythms: Shaping the Film Edit. Amsterdam: Focal Press/Elsevier, 2009.

Reynolds, Dee. "Kinesthetic Empathy and the Dance's Body: From Emotion to Affect." In Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason (Eds.) Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices. London: Intellect, 2012. 121-136.

Reynolds, Dee and Matthew Reason (Eds.) Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices. London: Intellect, 2012.

Siegel, Marcia B. "Visible Secrets." In Gay Morris (Ed.) Moving Words: Re-Writing Dance. New York: Routledge, 1996. 29-42.

The Truth. Dir. Katrina McPherson. Chor. Paulo Ribeiro and Fin Walker. Prod. Goat. 2003. Film.

White, John. Discussion with Katrina McPherson, independent artist. July 29, 2015.

White, John. Discussion with Simon Fildes, independent artist. June 26, 2015.

Williams, Linda. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the "Frenzy of the Visible." Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989.

Wood, Karen. "Audience as Community: Corporeal Knowledge and Empathetic Viewing." International Journal of Screendance 5 (2015): 29-42. https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v5i0.4518

----. "Kinesthetic Empathy: Conditions for Viewing.” In Douglas Rosenberg (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. 245-261.

Notes

For a thorough and comprehensive history of the origins of "kinesthetic empathy" as a term, see Susan Leigh Foster, Choreographing Empathy. I also found the very wide-ranging topics covered in Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason's Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices to provide invaluable context, as well as Karen Wood's "Kinesthetic Empathy" and Katrina McPherson's Making Video Dance.↩

Foster, 123.↩

Wood writes in 2016 that "[t]here is … no research to date in dance or film studies on the kinesthetic experience of watching screendance." Wood, "Kinesthetic Empathy," 247. In the article she studies audiences' kinesthetic and emotional responses to screendance and how filmic techniques like synchronicity between movement and music, defamiliarization, and narrative structures influence those responses. Wood published similar research on audiences' kinesthetic and empathetic responses to screendance in Wood, "Audience as Community."↩

In particular I rely on McPherson's instructional book Making Video Dance, as well as Erin Brannigan's Dancefilm and Karen Pearlman's Cutting Rhythms.↩

Wood, "Kinesthetic Empathy," 251.↩

I take the term "choreographed camera" from McPherson, Making Video Dance, 24.↩

See "Dance and the Camera" in Idem, 22-40.↩

Foster, 10.↩

Reynolds, "Kinesthetic Empathy," 124.↩

Ibid.↩

Idem, 127.↩

Idem, 132.↩

Siegel, "Visible Secrets," 31.↩

McPherson, Making Video Dance, 24.↩

McPherson, “A Passion for Screendance,” 49.↩

Deleuze, cited in Brannigan, 48.↩

Brannigan, 45.↩

Idem, 51.↩

Idem, 44.↩

Wood, "Kinesthetic Empathy," 247.↩

McPherson, Making Video Dance, 189.↩

Foster discussing Hagendoorn, 167.↩

Ibid.↩

Pearlman, 11.↩

Idem, 17.↩

Wood, "Kinesthetic Empathy," 253.↩

Pearlman, 17.↩

For a thorough analysis of embodied responses to genre film, see Sarah Friedland, "The Meaning of the Moves."↩

Reynolds, 124.↩

Clay Calvert, Voyeur Nation, 2.↩

John White, discussion with Simon Fildes.↩

Robert Knifton, "You’ll Never Walk Alone," 83.↩

David Lyon, The Electronic Eye, 4.↩

John McGrath, Loving Big Brother, 5.↩

Knifton, 88.↩

Idem, 88-89.↩

Linda Williams, Hard Core, 46.↩

Ibid.↩

Maciej Ożóg, "Surveilling the Surveillance Society," 97.↩

Lyon, 180.↩

For a related exploration of "reading sexualized voyeurism and exhibitionism which deploys a 'surveillance aesthetic' as cultural critique, even as emancipatory action," see Bell, "Surveillance is Sexy."↩

Lyon, 182.↩

Foster writes, "Increasingly, individuals, jacked into their globally dispersed contacts, ignore the rituals and protocols that have defined public space. They do not partake in the protocols of civil exchange that defined eighteenth century comportment, nor do they observe the strong opposition between public and domestic spaces that dominated the nineteenth century. Instead, they rely on technologies of surveillance that monitor public behavior to provide the common ground on which they move." Foster, 189.↩

For a detailed account of the planning and execution of filming The Truth see McPherson, Making Video Dance, 225-246.↩

White, discussion with McPherson.↩

McGrath, 78.↩

Jeffrey Bush and Peter Z. Grossman, "Videodance," 13.↩

Foster, 195.↩

Ibid.↩

For Magid's own words on the project see Embedded – Jill Magid.↩

The process for viewing the footage and receiving emailed copies of the forms/letters is detailed at Magid, Evidence Locker. The forms/letters are also available in book form, see Magid, One Cycle of Memory in the City of L.↩

Magid, from emailed copy of letter #17.↩

Magid, from emailed copy of letter #2.↩

Magid, from emailed copy of letter #24.↩

Knifton, 91.↩

Magid, from emailed copy of letter #30.↩

McGrath, 209.↩

Idem, 210.↩