Danced Out: When Passing for Almost Straight Is Not Enough

Mark Broomfield, State University of New York at Geneseo

Keywords: screendance, documentary, LGBTQ, race, gender performance, masculinity, western theatrical dance

Danced Out emerges from my lived experience as a professional male dancer. In a world filled with anxiety about masculinity, and the policing of its boundaries, this documentary film shares my deep commitment to understanding, exploring, and revealing the multifaceted aspects of gender performance. It shows the crucial function gay men have in contemporary society and culture. With its nuanced approach, Danced Out offers critical insights that challenge individuals, institutions, and society that perpetuate gender norms about masculinity.

Danced Out challenges the longstanding default associations of Western theatrical dance as a welcoming safe space for gay men and queer male dancing bodies.1 At root, the documentary gives visibility to the complicated and contradictory notions of masculine gender performance by gay men in dance. More specifically, the film illuminates the critical role and function that gay men play in both destabilizing and deconstructing social expectations of gender performance on and offstage.

The documentary speaks to myriad ways in which homophobia, sexism, misogyny and the policing of masculinity constrains diverse masculinities and gender expression. Danced Out raises questions about the different set of political stakes and investments in performing masculinity that gay male dancers experience and heterosexual men might not. It does so while also recognizing the multiplicity and spectrum of gender expression for gender nonconforming, gender non-binary, and LGBTQ identified people. In sum, masculine gender performance is not tied to the cisgender heterosexual white middle class male body. The film centers the experiences of gay male dancers of color to both reimagine and redefine masculinity for the twenty-first century. Indeed, assumptions about masculinity in dance and popular culture routinely ignore the lived experiences of gay men. In fact, gay men are not considered "masculine," nor are they assumed to be.2 Danced Out challenges this false perception.

Heterosexual men do not have a monopoly on masculinity—and never have. Gay male dancers in the tradition of Western theatrical dance have been dancing out for decades. No one seemed to notice, however, because they looked "straight." Gay men have been "straight acting" before the phenomena bore its current name.3 Imagine, how have gay male dancers accomplished this feat? For the purposes of my documentary feature film Danced Out, I coin the phrase "passing for almost straight" to examine a contemporary manifestation of sexual passing.

Danced Out represents the collective exhaustion, among gay men in dance, of playing "straight" roles on and offstage. Like theatre, and drag performances, gay male dancers break the fourth wall by exposing societal gender norms and the fragility of masculinity.4 These gay men share an intimate relationship with masculinity that many heterosexual men do not.5 Gay men can perhaps see more clearly than most, that masculinity is in fact—a performance.6 Gay male dancers routinely grow up being told heterosexual men define masculinity, shamed by a masculine ideal to which they purportedly do not fit. The men in Danced Out own masculinity in all its complexity. The film demonstrates the indispensable social role gay men have redefining masculinity in American contemporary culture.

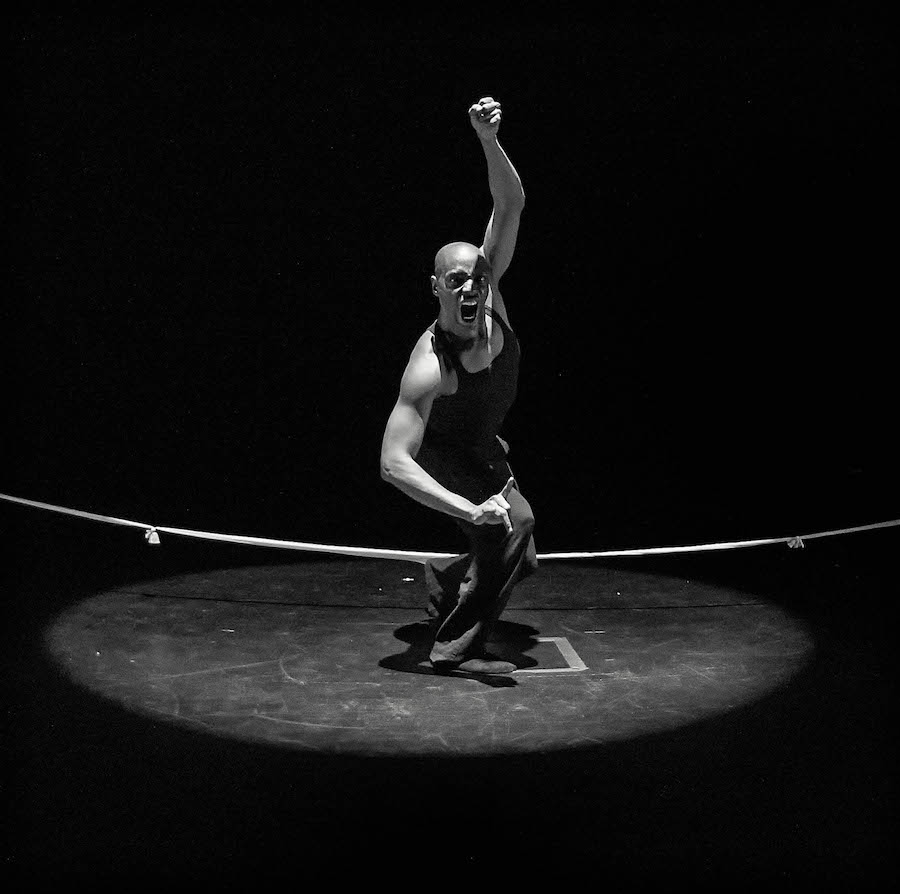

Germaul Barnes. Photo by Marc Millman

In a culture that views gender largely through visual codes, the inability to distinguish between gay and straight men poses a threat to dominant notions of masculinity.7 On one hand, these visual codes determine the legibility and legitimacy of men's social relations based on power and status. On the other hand, the inability to distinguish heterosexual and homosexual men faces repeated calls for gay men to "do out." For some "doing out" might include engaging in public displays of same-sex affection, embodying stereotypes of gay men as effeminate, sissies, or "flamboyant." In the absence of these performances, it makes identifying distinctions between heterosexual and gay masculinities that much more difficult. The inability to largely make distinctions between "gay" and "straight" masculinities gives greater credence to how "passing for almost straight" functions—not as an act of duplicity—but as a means of strategizing survival based on social expectations and gendered bodily norms.

Constrained on the spectrum of gender expression from hypermasculine to hyperfeminine, gay men are critiqued if their gender performance is perceived as conforming to gender norms, in other words, sexual passing; and on the other hand, critiqued if their gender performance is perceived as feminine—deemed "too out."8 When heterosexuality is presumed and normative, passing—although it historically has depended on markers of visibility that approximate whiteness—does allow gay men to survive.9 When gay men successfully pass as straight by imitating the codes and gendered performance of heterosexual masculinity, or in the case of "straight acting" they are in large part made invisible.10

Gay men face repeated calls to "come out." However, the term is misapplied, and it is essentially a call for "doing out" that signals the human need to categorize and make selections about sexuality based on gender performance. Because the documentary features many black gay male dancers, the related phenomenon of the "down low" ("DL"), black men who do not identify as gay but who have sex with men, and who practice heterosexual norms of masculinity—underscores issues of race to sexual passing.11

In his book, Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing, gender studies scholar Jeffrey McCune's dual framing of the DL yields important insights about black masculinity, sexuality, identity, and gender performance. By making distinctions between discreet and discrete sexual practices of black men who have sex with men who do not identify as gay, McCune reveals how the DL functions as a space of sexual freedom and autonomy outside state surveillance of black bodies. His work rejects the closet as a liberatory space for queer of color LGBTQ people.12 State surveillance of black bodies coupled with dominant masculine gender performances, along with notions of men on the DL, and policing masculinity disrupt narratives about black gay men as deviant and pathological. Thus, this "passing for almost straight" demonstrates the multiple configurations that conceal my theorization of "doing out."

Brother(hood) Dance! (dancers Ricardo Valentine and Orlando Zane Hunter). Photo by Ian Douglas

Unlike white men in dance, whose bodies function as the abstract universal norm, black gay male dancers face a culture in which race and sexuality significantly marks their difference.13 In American culture, black men vacillate between hypervisibility and invisibility coupled with heightened surveillance.14 Arguably, queering the white body follows a narrative trajectory of liberation and emancipation, whereas blackness is itself already queer according to normative standards of whiteness. And so being queer functions differently for the black male dancing body, which complicates sexual passing.

Sexual passing is not about "coming out." The male dancers in Danced Out all self-identify as gay. The historical focus of LGBTQ people to "come out" of the closet emphasizes it as a one-time act. Therein lies the tension between "coming out" and the ethics of sexual passing. In its call to all LGBTQ people to "come out," nuances of what "coming out" individually means are hidden. In fact, "coming out" is not a one-time act, but a life sentence to "coming out." In the documentary, my conceptualization of "passing for almost straight," denotes the ethics of sexual passing as strategic gender performances and the performance of identity. It requires navigating spaces that necessitates deft perception of each encounter, and the risk of certain behaviors not deemed masculine enough.

"Passing for almost straight" implicates an explicit correlation to a "straight" sexual identity. Yet, while "straight" signifies heterosexuality, it is actually a code for masculine gender performance. Therefore "straight" passes as the performance of masculinity. "Straight" assumes heterosexuality is tied to dominant masculinity. It even has its own terminology "straight acting." Highly desirable, the phenomenon of "straight acting," reveals its potency among men in the gay community. The premium for both heterosexual and gay men: dominant masculinity. "Natural" in heterosexual men, and "appropriated" in gay men. Perceptions about "straight" men require debunking. In fact, "straight" men have no more ownership of masculinity than gay men. Therein lies the ultimate threat to heterosexuality and masculine gender performance—the role that gay men play in exposing the illusions of gender performance.

Gay black male dancers use strategic gender performances in how they seek to embody masculinity because, while hegemonic masculinity applies to all men, it performs differently for black men in American society. This strategizing of gender performance aligns with Ramón Rivera-Servera's definition of queer as a position and strategy. "As a strategy, 'to act queer' refers to the set of practices engaged by queers themselves in their creative navigation of everyday life in a heteronormative society."15 Failure to achieve and maintain dominance exposes black men to criticisms of emasculation, weakness, or not being "real" men.16 Far removed from the white masculine ideal, black gay men have a history of using performance and performative techniques to negotiate and navigate their survival.17

Desmond Richardson. Photo by Gene Schiavone

Desmond Richardson, former principal dancer with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, co-artistic director of Complexions Contemporary Ballet, and dance icon, explained to me that even early on, as he was learning the art form, he was aware that dance was a feminized space, calling on him and others to prove their masculinity.18 Because gay men grow up in a homophobic culture that repudiates any equation of homosexuality and masculinity, their early awareness of gender sets in motion a distinction between who they are and what they do.19 Consequently, these men are more inclined to see gender as an act, as performance, as theatre—and as play. This distinguishes gay men, and especially gay male dancers, from their straight counterparts.

The gender and sexual outlaw status of the gay men in Danced Out, reveals a gendered double consciousness that represents the different stakes and investments of performing masculinity due to their sexual identity. Gay men have a history of using performative techniques to navigate their survival in a homophobic culture.20 The stigma associated with their sexual identity leaves many gay men struggling with internalized homophobia. Society frowns upon performances of gay men perceived as "too out." The phenomenon of "passing for almost straight" pertains to men who do not self-identify as straight, although their behavior and gender performance can be read as such. "Passing for almost straight" reveals the pressure to perform and constantly prove heteronormative masculinity. The persistent requirement to police one's gender performance, the self-surveillance it requires, and the psychological exhaustion resulting from continually policing one's behavior all take an oppressive toll.21

Danced Out demonstrates the tensions of gay men passing between multiple spaces. In a world often filled with uncertainty about maleness and masculinity, the "gay" male dancing body, to a degree, creates even more uncertainty by exposing the fictions of masculinity. Danced Out confounds the stereotyped popular perceptions and images of male dancers by calling into question the incompatibility of masculinity and "gayness."

Biography

Mark Broomfield, Assistant Professor of Dance Studies and Associate Director of the Geneseo Dance Ensemble in the Department of Theatre and Dance at SUNY Geneseo (PhD, MFA), is a scholar/artist who has danced with the repertory company Cleo Parker Robinson Dance, performing in leading works by some of the most diverse and recognized African American choreographers in the American modern dance tradition that include: Talley Beatty, Katherine Dunham, Eleo Pomare, Donald McKayle, David Rousseve, and Ronald K. Brown. His publications include the article "Branding Ailey: The Embodied Resistance of the Queer Black Male Dancing Body" by Oxford Handbooks Online and his poem "Passing Out" in Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies. Two forthcoming book chapters include "'Doing Out': A Black Dandy Defies Gender Norms in the Bronx" by Vanderbilt University Press and "So You Think You Are Masculine? Dance Reality Television, Spectatorship, and Gender Nonconformity" by Routledge. He is currently working on his book Passing for Almost Straight: Queer Black Masculinities in American Contemporary Dance and documentary Danced Out. Broomfield is the recipient of the Woodrow Wilson Career Enhancement Fellowship, the SUNY Faculty Diversity Award, and the Ford Foundation Fellowship.

Email:

Website: www.markbroomfield.org

References

Bailey, Marlon M. Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance and the Ballroom Culture in Detroit. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.799908

Barnes, Germaul. In interview with author, April 29, 2009.

Brown, Ronald K. In interview with author, August 15, 2008.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male Under World 1890-1940. New York: BasicBooks, 1994.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Connell, R. W. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

___. "A Very Straight Gay: Masculinity, Homosexual Experience, and the Dynamics of Gender." American Sociological Review, 57, no. 6 (Dec. 1992), 735-751. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096120

Craig, Maxine Leeds. Sorry I Don't Dance: Why Men Refuse to Dance. New York: Oxford, 2014.

Eng, David. The Feeling of Kinship: Queer Liberalism and the Racialization of Intimacy. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392828

Fisher, Jennifer. "Make It Maverick: Rethinking the 'Make it Macho' Strategy for Men in Ballet." Dance Chronicle, 30, no. 1 (March 2007): 51. https://doi.org/10.1080/01472520601163854

Halberstam, Judith. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394358

Isaac, William. In interview with author, June 18, 2008.

Harrison, Kelby. Sexual Deceit: The Ethics of Passing. New York: Lexington Books, 2013.

King, Deborah K. Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

McCune Jr., Jeffrey Q. Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

McCready, Lance T. Making Space for Diverse Masculinities: Difference, Intersectionality, and Engagement in an Urban High School. New York: Peter Lang, 2010. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-0000-0

Migdalek, Jack. The Embodied Performance of Gender. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Moore, Fiona. "One of the Gals Who's One of the Guys, Masculinity and Drag Performance in North America." In Changing Sex and Bending Gender. Eds. Alison Shaw and Shirley Ardener. New York: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Neal, Mark Anthony. Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

___. New Black Man. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Richardson, Desmond. In interview with author, September 15, 2008.

Risner, Doug. Stigma and Perseverance in the Lives of Boys Who Dance. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

Rivera-Servera, Ramón H. Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.2395967

Roberts, Frank Leon. In interview with author, October 16, 2009.

Stoneley, Peter. A Queer History of the Ballet. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Ward, Jane. Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men. New York: New York University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479860685.001.0001

Whitehead, Stephen M. Men and Masculinities: Key Themes and Directions. Malden: Polity Press, 2002.

Yoshino, Kenji. "Covering." The Yale Law Journal, 111, no. 4 (Jan 2002), 769-939. https://doi.org/10.2307/797566

Notes

Stoneley, A Queer History of the Ballet, 2; Risner, Stigma and Perseverance, 6-7; Fisher, "Make It Maverick," 51.↩

Neal, New Black Man, 155.↩

Chauncey, Gay New York, 6-7; Yoshino, "Covering," 935-36.↩

Moore, "One of the Gals Who's One of the Guys," 110.↩

Frank Leon Roberts (Scholar/Activist), in interview with author.↩

Aubrey Lynch, (Former Principal Dancer Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre), in interview with author.↩

Whitehead, Men and Masculinities, 219. Ronald K. Brown (Artistic Director, Evidence), in interview with author. Brown discusses not being on the DL and not being straight acting. Germaul Barnes, (Artistic Director, Viewsic Dance), in interview with author. Barnes denotes that we are at a point where making distinctions gay and straight masculinities are hard to observe, questioning, "What is going on?"↩

McCready, Making Space for Diverse Masculinities, 78-80.↩

William Isaac, (Dancer), in interview with author. Isaac discusses the tensions of "doing out" and the need to survive.↩

Harrison, Sexual Deceit, 6.↩

McCune, Jr., Sexual Discretion, 8.↩

Eng, The Feeling of Kinship, 27-8.↩

Ward, Not Gay, 24-5; McCready, 9-10.↩

Neal, Looking for Leroy, 4-5.↩

Rivera-Servera, Performing Queer Latinidad, 27.↩

Collins, Black Sexual Politics, 74-5.↩

Bailey, Butch Queens Up in Pumps, 17-18.↩

Desmond Richardson (Artistic Director, Complexions Contemporary Ballet), in interview with author.↩

Connell, "A Very Straight Gay," 736.↩

Chauncey, 187-8; McCready, 72-73; Richardson. Richardson discusses the performance of masculinity in different spaces.↩

Migdalek, The Embodied Performance of Gender, 27-8.↩