TikTok, Friendship, and Sipping Tea, or How to Endure a Pandemic

Melissa Blanco Borelli, Associate Professor, School of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies, University of Maryland

madison moore, Assistant Professor, Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University

Keywords: TikTok, queer performance, music, social media, popular dance on screen, race, critical friendship

TikTok is a short-form social media app on which users create brief, pithy, and endlessly shareable performances on video that last 60 seconds or less. When you open TikTok you’re taken to the For You Page (after a compulsory ad plays), an endless stream of video content curated “for you” by algorithms that use your prior engagement with the app to show you the kind of content it assumes you want to see, beaming content onto screens the algorithm thinks you are most likely to enjoy.[1] Depending on which “side” of TikTok you train the algorithm to put you on, your For You Page might show you far-right conspiracy theories and cat videos, or you might see drag makeup tutorials, cooking how-tos, hot takes on current events and queer people of color dancing to jams like “WAP” by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion.

These types of brief performances are intended for the phone screen, with artificial intelligence driving the app’s capabilities to loop, distort, and alter images and video. For performance studies scholars, TikTok evinces what Elise Morrison, Tavia Nyong’o, and Joseph Roach move us to think of as the “algorithmic performative,” noting that “it has become increasingly difficult in this day and age to use the term “performance” without calling up an algorithmic matrix of input/output, cause and effect.”[2] In similar fashion, we also see TikTok enacting what Sianne Ngai would call a “capitalist gimmick.”[3] This gimmick “is both a wonder and a trick. It is a form we marvel at and distrust, admire and disdain, whose affective intensity for us increases precisely because of this ambivalence.”[4] These critical frames could not be more relevant in 2020 and beyond.

2020 has been an unprecedented historical moment where in-person events in the USA have been cancelled for over a year at the time of this writing due to the coronavirus pandemic. During this time when the live arts have moved from the stage to the screen, TikTok offers a fascinating venue to consider the “sets of meanings and conventions” implied, innovated and reiterated in quotidian performance practices.[5] Recently, Black feminist scholars have been shaping thought around the racist logics built into algorithmic processes. Ruha Benjamin, for example, calls these processes “coded inequity” and Safiya Noble uses the term “algorithmic oppression.”[6]When articulating the performance cultures of a social media app like TikTok, an app that relies on the endless circulation of relatable content, performance scholars might take up Simone Brown’s question: “how do we understand the body once it is made into data?”[7] In this, examining TikTok through a critical dance and performance studies lens offers a multiplicity of ways to see how the body-as-data is mobilized through gesture, dance, fashion, speech acts, and choreography. With its rise in popularity during the pandemic, in addition to the machinations by the Trump Administration to ban TikTok in the United States, TikTok exists as a rich, neoliberally activated virtual stage that moves across pleasure, politics, and personality.[8]

Over the past year, the authors of this piece have sent each other dozens of TikTok videos via Facebook Messenger, sometimes in the middle of the night. Due to the isolation and unparalleled loss of social life brought on by the pandemic, these videos worked to rearticulate our friendship. That dialogue, the call and response of sharing 60-second performance content, led us to position this piece as a conversation. We thought we could model our friendship and pleasurable exchanges for you in a way that resembles the kinds of sociality that TikTok allows. What follows is our way of thinking about TikTok through our enjoyment of it as a compelling site of contemporary performance.

madison moore: I am so glad to be in conversation with you about TikTok, particularly given the way you think about popular dance, screens, and performance. I think what I find so compelling about TikTok is that it extends what John Muse calls “microdramas,” or incredibly brief performances that challenge temporal structure.[9] Muse points out that there is a long history of really brief performance, and I think TikTok videos are a great example of that because they can only be a minute long, not more. That temporal limit presents an incredibly tight but exciting range of performance possibilities. I even tried using TikTok in my classes in Fall 2020 in lieu of assigning writing responses as a pedagogical exercise. Some of my students did them and loved it, but others complained about how difficult it was to come up with even a 15-second video every week. Compelling short performances are tough! So I’d be really interested to hear what strikes you about TikTok and how the app differs from other social media platforms for you in terms of its connections to performance-making and the everyday.

Melissa Blanco Borelli: Well, I tried to do weekly TikToks for my graduate seminar in Performance Studies, but I gave up less than halfway through the semester because I realized how labor intensive making a quality TikTok can be. But, I am so glad you turned me onto it this past summer when we were having our usual Facebook messenger catch-ups. I saved all the TikToks you initially shared with me. I was enthralled from the start. I remember you telling me that you had stopped watching movies or television in the evenings and you were exclusively watching TikTok. I started doing the same and I understood TikTok’s allure. I began to notice how each video is a micro-performance of daily life, imagination, pleasure, and ways of coping with Covid-19 lockdowns happening across the world. Each short video is a new world. Content creators expand on already known dances, quotes from films or television shows, they engage in citational, presentational, and/or satirical practices about their tastes, culture, passions, or skills. TikTok offers relatively easy to use (with practice and lots of trial and error) editing tools such as duet capability and green screen, so that there are endless possibilities and variations available for your video. It need not look like anybody else’s video, but part of the way that community is created through TikTok is through the circulation, repetition, and re-interpretation of performative conceits that somehow show how your video does look like another one. TikTok becomes this space of performance surrogation,[10] where the user’s literacy (of the TikTok archive) and knowledge comes to play depending on how they engage with pre-existing TikToks thereby contributing to what I would call a contemporary genealogy of digital performance. TikTok also functions as a digital commons, a space where “difference” seems obsolete because in order to belong, you just have to join TikTok, know the parameters of how to make a video and then use it according to your own skills and aesthetic preferences. This digital commons of TikTok offers up a creative, collaborative, and even critical space to comment on the current moment. Harmony Bench asks several questions in her book Perpetual Motion that feel relevant here to our discussion: “What can dance, movement, and gesture afford—and what conflicts arise—when they are perceived as common or utilized to enact a common? How, why, and for whom are assertions of dance as common meaningful in digital contexts?”[11] I think the lockdown experience of the pandemic allowed the digital commons of TikTok to expand and become a crucial survival mechanism for many. It became a way, through all types of embodied performances (dance, cooking, crafting, acting) and performative tactics to make sense of our world and participate in the misery of lockdown and pandemic fear together. So, while TikTok’s accessibility and usability set it up as a commons, I think you are right in bringing up the algorithm (and the algorithms of race) that lie beneath its seemingly universal veneer. Bench writes about a participatory commons as “as an alternative to the extractive neoliberal financial logics that govern much of contemporary life in the United States and beyond.”[12] Yet, TikTok is most definitely a product of neoliberalism’s marketing and commodification of the self through social media. The tension between TikTok functioning as a participatory commons outside of neoliberal financial logics while simultaneously being a product of the neoliberal financialization of the self makes it the perfect stage for critical dance and performance analysis. Such critical framing helps me to unpack and justify my pleasure in TikTok. Not that one’s pleasure’s need justification, mind you, hahaha, we both know that!

madison: Right! It’s a question of both/and here, and I think the contradictory nature of TikTok as a space of possibility and a space where folks can do hot takes on popular culture and a space deeply tied to flows of capital is what makes it such an interesting venue to think about contemporary performance onscreen. We can agree that TikTok absolutely is a product of the neoliberal financialization of the self. Part of the allure of the app is the way it creates the kind of participatory commons through shared performance content. I knew about TikTok for a while as a friend of mine used to send me TikToks all the time, imploring me to get on the app because it was the next new social media phenomenon. I was missing out, he told me. At the time, I didn’t take the app seriously. My data is already owned by the dozens of social media apps already installed on my phone, so the last thing I needed was another one. It was not until the pandemic dramatically altered quotidian life, the live arts, and reoriented notions of time and leisure that I downloaded the app and fell down the rabbit hole, as it were. Purely in terms of the content, I could not stop laughing at the short-form performances I landed on and really found it difficult to stop scrolling. 1am became 3am became 5am, all scrolling, the algorithm learning more and more about my taste and showing me even more precise videos tailored to my liking, making it that much harder for me to put it down.

No better TikTok captures that feeling of endless scrolling than one I saw recently of @the_mannii in bed late at night wearing a blue eye mask and holding their phone in hand in the dark. A laughing track plays in the background and the video banner says, “Me dying from TikTok videos at 4am and my alarm is set for 7am.” That was basically me all summer!

But even as I embrace the potential for worldmaking on the app, I am also aware and wary of the ways TikTok is programmed solely to capitalize on my attention. I’m thinking of Shaka McGlotten here, who writes so beautifully about the ways technology, data, and algorithms impact our daily lives. McGlotten is interested in how these systems “hack our desires in increasingly molecular ways,” encouraging us to keep “our eyes glued to screens and our bodies arranged around our phones or otherwise contorted, our fingers tapping, typing, swiping, and scrolling away.”[13] The fact that I stopped watching TV in favor of TikTok is a prime example of the power of my catered TikTok algorithm, which computer scientist Tristan Harris notes is designed to do exactly this. “If you want to maximize addictiveness,” he wrote in an article that appeared in the Observer, “all tech designers need to do is link a user’s action (like pulling a lever) with a variable reward.”[14] It’s the roulette wheel or slot machine effect that, when programmed correctly, wins no matter what you choose.

I think the thing that kept me pulling the lever on TikTok was that I unknowingly trained my algorithm to constantly spit out a reliable, endless stream of Black queer performance that, first of all, I was certainly not seeing in other media spheres where there continues to be a problem telling stories that aren’t about white people. But the other reason I kept pulling the lever is that, deep in the darkness of the initial lockdown and the sudden lack of live art, I was able to find avenues of pleasure, joy, and human “connection” through these algorithmic performances. There was something important to me about the collective feeling of loneliness, depression and anxiety that came from the large-scale cancellation of public entertainment, coupled with an enduring sense of hope in a stream of videos which highlighted that even in the darkest hour, the show must go on.

Melissa: Since we both respond so pleasurably to the worldmaking performative potential of TikTok, I’m wondering how does TikTok generate a digital space for users to perform an/their identity? I know we share giggles and guffaws over particular videos of queer extravagance (@themanuelsantos) or rasquache aesthetics (@birdmartinez2) so I wonder how this platform allows for such performances to be possible.[15] Again, here I am thinking of what Ngai writes about the gimmick: “Labor, time, value: the contradictions that explain why the gimmick simultaneously annoys and attracts us explain why it permeates virtually every aspect of capitalist life.”[16] If each TikTok video can be interpreted as a gimmick, how do these videos corporealize labor, time, and value so that we can see the process of performance and self-making through performance?

@birdmartinez2 How I do my hair #birdMartinez

♬ original sound - Bird Martinez

madison: Child, don’t get me started on @birdmartinez2! I live for her.[17] She might be my favorite TikToker because of her complete lack of interest in respectability politics, alongside other Black queer content creators like @headoftheehoochies. For those who don’t know, @birdmartinez2 is a Latinx diva who makes videos about how to make Mexican dishes. TikTok is certainly full of cooking videos and how-tos, but what makes @birdmartinez2 so compelling is the ratchet-rasquache, working-class aesthetic, with the red lip, the dramatic bat-winged eye makeup, the gaudy gold earrings and the big, bouffant hair piled on top of her head. Her videos are punctuated by the phrase “bitch...bitch...bitch” said performatively in a cadence familiar to Black and Latinx queer and trans people. She is truly a gem, and offers a prime example of what Jillian Hernandez calls “aesthetic excess,” or the debates that mark “Black and Latina bodies as fake, low-class, ugly, sexually deviant, and thus damaging to the public image of their communities.”[18]

@birdmartinez2 is a perfect example of how in certain ways TikTok allows a space for queer extravagance and ratchet aesthetics because it is in the app’s favor to operate as a marketplace for a poetics of the self because similar users will find these performances of fabulousness content and feel “seen.” In turn, that encourages users drawn to queer extravagance to spend more time on the app, which then will spit out even more related content, which keeps the user logged in. The house wins. As Ruha Benjamin warns, illusions of progress that we might assume because we see more marginalized people on screen allows “racist habits and logics to enter through the backdoor of tech design, in which the humans who create the algorithms are hidden from view.”[19] That being said, I still believe a poetics of the self is important when you are multiply marginalized because you don’t necessarily always have the access or the resources to cultivate visibility in the cultural sphere. At a basic level, on TikTok all you need is a smartphone and an idea to bring your microdrama to life.

Melissa: OMG, yes, Bird Martinez is definitely una joya! For me, Bird possesses this enthralling mix of (decolonial) self-love and validation mixed with a keen self-awareness and self-deprecation (“I know I look a little musty, a little motherfu$in’ crusty but always motherfu$in’ lusty… at least that’s what my husband says”). She peppers her Spanglish videos with humorous profanity. She draws you in as you wait to hear when and, more importantly, how the Spanish or the word muthafu$a will make their appearance. Her cursing is excessive; her hair and make-up while cooking seem excessive and impractical (won’t the labor of cooking and the steaming pots melt her foundation and eyeliner?); and her commentary sometimes borders on too much information about her personal life. Mind you, this is not a critique. I am drawn to that excess. In fact, I cannot get enough. There is skill and humor in how she moves between all of these excessive expressivities. I appreciate you bringing up Jillian Hernandez and her important work for this context. Hernandez explains that “the aesthetics of excess embrace abundance where the political order would impose austerity upon the racialized poor and working class.”[20] She further writes that “to present aesthetic excess is to make oneself hypervisible, but not necessarily in an effort to gain legibility or legitimacy […] it’s how we dress in the undercommons.”[21] Bird’s aesthetics of excess creates an intimate sociality. She invites us into her kitchen, she shares her lexicon and her pleasure and skill at Mexican-American cooking. Her quotidian undercommons may not necessarily attract huge followers (I can’t believe she only has 35.2K followers?!), but that is exactly what makes her videos so powerful. They are there for her and nobody else, really, yet as her fan, you feel like you are part of her intimate and privileged circle. She’s that cool girl you desperately want to be friends with and you can’t believe she’s so warm and inviting.

madison: I love that! Yes, there’s so much self-love, assertion, and self-awareness. I also love how you are thinking about the many forms of excess in her videos, from the cussing to the big hair. Of course, TikTok’s algorithm also reifies white standards of beauty as well as the kinds of bodies that are seen as desirable. TikTok certainly rewards, recirculates, and repositions images of whiteness as the most desirable.

Screenshot of @martinadene applying Fenty make-up

Melissa: That white femme beauty standard is such a violent one to dismantle and I see it to many differing degrees of success and failure, but I am mostly inspired by the Gen Z TikTokkers who blatantly reject these white standards. Young Black and Brown femme girls specifically turn to aesthetics and sensibilities from their culturally specific locations and sometimes even call out the tyranny of white femme aesthetics. I am particularly drawn to the TikToks by Nakota Navajo woman @martinadene. Her aesthetic practice on TikTok seamlessly amalgamates how she is indigenous, a fan of hip hop culture, and makeup tutorials. I think it is these intercultural practices of identity formation that do not adhere to any specific hierarchy but rather become a negotiated (often experienced as creative) conglomeration of our experiences and our tastes that I find so rich on TikTok. Case in point with Martina: she can be both indigenous and fabulous. She can wear Fenty lipstick and dance fiercely at a powwow. But, it does seem that videos that remain within the white standards of TikTok form and content aesthetics that get the most followers.

madison: One of the most fascinating, mind-bending aspects of TikTok is both the ways people perform their identities and how these identities are curated on the For You Page of each individual user. The For You Page is an algorithmically driven, randomized roulette wheel of videos. This roulette wheel creates different “sides” of TikTok, which at first glance might seem like an echo chamber of sorts, similar to how our Instagram or Facebook feeds are also curated to the content we like. But TikTok takes it a step further because your activity on the app foreshadows the kinds of randomized videos you will see and thus the “side” of TikTok you will be on. The app does what you tell it to do. But what is really interesting are the countless videos of queer people saying things like, “If I land on your For You Page, you’re queer and I love you” or otherwise pleading other queer users to engage with their content so they can “get out of straight TikTok.” In my own case, my For You Page shows me short performances mostly by Black women, femmes, trans people of color, gays, as well as anti-Trump people, nightlife queens and fashion videos. I have no idea what kinds of videos other people see. What “side” of TikTok are you on?

Melissa: Hahaha. Well, first when you told me about it I was on the For You Page. Since I had not started “liking” any videos I was beholden to a random algorithm: videos with mostly white teens doing silly things. Initially I thought this is definitely not for me. Thankfully, you started sending me the videos you thought were funny, smart, performative, witty by mostly Black women, femmes, gays and they were about fashion, fabulousness, dance and dressing up. I purposefully started liking them so the algorithm could curate my feed better. I also started engaging with the hashtags to find material that I fancied and started saving, following or liking. One magical day, I logged onto TikTok and felt its algorithm FINALLY understood what I wanted to see: a mixture of Black and Brown queer, femme and camp performance peppered with make-up tutorials, clever dance choreographies, and Schitt’s Creek, The Crown or Golden Girls parodies.

I find I am drawn to content creators who stick with one concept but play around with it. It reminds me of what Diana Taylor writes about performance, that, “performance—as reiterated corporeal behaviors—functions within a system of codes and conventions in which behaviors are reiterated, re-acted, reinvented, or relived. Performance is a constant state of again-ness.”[22] For example, there is this one user @sahdsimone who uses the same music (Coño (feat. Jhorrmountain x Adje)) to make his self-help dance videos. He sashays to the beat of the song towards the camera. He circles his head, rotates his hips and gets down into the groove of the music. Once three percussive beats punctuate the song, he uses each beat to point to text that appears on the screen. It offers self-help advice in the form of simple sentences: Just in case you need a reminder. Wait for it. Your kindness can save someone’s life; Just in case you need a reminder. Wait for it. Joy is in your DNA; orIn case you need a reminder. Wait for it. You are a legend. He flips his head, turns and sashays away. End TikTok. Once I saw several, I knew what his gimmick was, but each new TikTok brings the surprise of a new reminder so I keep watching.

madison: TikTok is a really thrilling place to see and think about dance cultures and performance worlds, especially during lockdown. Some of the videos I see the most are people talking about how much they miss nightlife and dancing in gay clubs. At one level, nightlife has always had to morph and shape-shift according to the political and cultural landscape of the moment. That’s why in states like Connecticut, Virginia and Pennsylvania, there are still blue laws that make public alcohol consumption legal only until 2am. But of course these legal restrictions only give way to new, more clandestine ways to consume offline. When the coronavirus pandemic pulled the curtain on the live arts overnight, and I’m including nightlife here as one of the richest forms of live art, rather than simply come to a complete stop, nightlife simply moved online to spaces like Zoom, Instagram Live, and gaming platforms like Twitch. Now, the dance floor is the chat room.

There are a range of TikTok videos that punctuate the collective feeling of missing the dance floor and all the chance encounters, cruising, flirting, kissing and holding space together that most of us long for again. In a performance by @bbyfangs, a persistent banner reads “POV: You are dancing with me at the gayclub in 2022.” They dance wildly in a little black dress in their bedroom, where most of us go clubbing these days, the colors in the room changing quickly from blue to green to red to evoke the dynamics of club lighting. A soundtrack of typical gay club music animates the minute-long video.

@bbyfangs I can’t wait I miss dancing drunk with queens #gayclub #queer #fyp #vibewithme #dance #beyourself

♬ original sound - Tom Phan

On the one hand, performances like these have a certain nostalgia for the dance floor we all once took for granted. And on the other, these performances show the significance of the ability to dance together to loud music on a dance floor in real time. Even in lockdown, “the girls” still want to dance, encapsulating the point made by Susan Leigh Foster that “there is always energy for dancing because it is so fun.”[23] When the club is closed, maybe TikTok is the best place to dance.

Melissa: It’s the best place for so many things… so much creative potential if you have the time to really play around with it. I think it’s a great place to experiment with one theme or “gimmick” and see how far you can take it. When I watch the videos made by @trevee.tv I am thinking about this quote by performance artist Tehching Hsieh: “Life is a life sentence,” he says. “Every minute, every minute is different. You cannot go back. Every time is different but we do the same thing.”[24] The life sentence of life is an opportunity to make declarative statements with and through your body as @trevee.tv chooses to do with his walking. He always has the same bouncy, purposeful biomechanical motion forward, but each TikTok video about “the walk” features a different context, framing, costume and background. In what I call his “Walking Choreographies” videos, @trevee.tv takes a prompt from a follower who asks him to “do a walk…” that is related to a particular life situation. It reminds me of choreography classes I took as a graduate student with Susan Rose who would ask us to “make a dance where…” and it was often a simple task-based request that had infinite creative possibilities. The choreographic task is implicit in the follower’s request. “Do a walk to: you got to the car and realized the cashier shorted you $2.00” leads @trevee.tv to create this piece:

@trevee.tv @amareiilibra “ I want all of my money back , even the CENTS ...” we are like this I believe 😂😂 #YouGotThis #MicellarRewind #trevee27 #thewalk

♬ original sound - 〖Ŧrͥevͣeͫe〗

“do the walk after you lost 2 lbs and feel like a whole new woman! Move bit%hes, a new me is coming through” offers us this:

@trevee.tv @rosanellymendez “ PERIODT 😂😂😂👌🏾 “ 2 lbs makes a big difference 👏🏾✨ ##trevee27 ##SFXMakeup ##ComingOfAge ##thewalk ##losingweight ##2lbs ##newwoman

♬ original sound - 〖Ŧrͥevͣeͫe〗

and “do the walk when you see that person take your parking spot” gives us this:

@trevee.tv Reply to @kasumislogic ##greenscreen “ Heffa “ 😂😂😅😂😂😅😅 ##razrfit ##DoggyAnthem ##FallAesthetic ##StrapBack ##trevee27 ##slomos ##slowmowalk ##thewalk

♬ The JUICE by MR FINGERS - Han

In each of these videos @trevee.tv engages in drag performance and dons a wig and femme style clothes (he usually wears a shawl, accented with a thin belt and carries a purse and a phone) to enact his interpretation of a determined and focused Black womanhood. The walk is usually accompanied by the same soundtrack, but he varies it on occasion. Once you see several, you begin to understand the choreographic/dramaturgic conceit. Audience anticipation and satisfaction stems from how well he dramatizes/choreographs the walking task proposed by his follower.

Of course, this is not without issue. madison, what do you think about the problematics of Black queer worldmaking at the expense of caricaturing Black femme aesthetics and Black cis-women? Part of me loves the performative and aesthetic conviction and commitment many of these Black queer femmes engage in, but I must raise an eyebrow and throw critical shade at how the Black woman becomes the brunt of jokes. How do we reconcile the Black queer worldmaking with the misogynoir on TikTok?[25] Or, is this tension part of the richness of TikTok as a site for cultural critique? I sent several of @trevee.tv’s videos to one of my most staunch Black feminist graduate students and she was both fascinated and annoyed. With her permission, I quote her here: “Okay, I loooooove this. I keep replaying it. It’s problematic but I hate to say how some of these fools get us [Black women] so right!”[26]

madison: WOW! That’s a heavy one. You know, I have also seen videos by Black women calling out gay men who get their followers from this kind of misogynoir. I wasn’t familiar with @trevee.tv’s performances, but they definitely make me think of @nasfromthegram, or “Thank you choosing McDonald’s, may I take your order please?” (Melissa: OMG, recently trevee.tv did a #duet with him here!) He makes sassy sketches about an impatient, imaginary McDonald’s teller, who is clearly meant to be working class, ratchet and presents the kinds of “ugly” aesthetic excess that Jillian Hernandez talks about. Nails (Melissa: he puts long silver hair pins as his nails, DYING!!), wigs, speech patterns, use of African American Vernacular English. So I agree with your student here and I join you in throwing some fierce critical shade. I have been crying laughing @nasfromthegram when his videos hit my feed (Melissa: yes, I hate to admit it but me too), but I also want to draw attention to the ways in which gay men continue to instrumentalize Black women for profit, a project that includes RuPaul, Tyler Perry, Shirley Q Liquor, and on and on. The same forms of aesthetic excess that lead to Black and Latinx being called “unprofessional” or “ugly” make Black gay men millionaires and billionaires, in the case of Tyler Perry. Case in point: @nasfromthegram has 1.3 million followers. MILLION. Who is his audience? Videos like these make me think about Safiya Noble’s notion of “technological redlining,” which is the power algorithms have to swiftly create, normalize, and reinforce stereotypes.[27] By contrast, Jeanette Reyes (@msnewslady), an Afro-Latina news anchor based in Washington D.C. who makes videos about code switching and the TV anchor accent only has 299,000 (January 2021. By 6 May 2021, she now has over 665,000).

Screenshot of @msnewslady.

One thing’s for sure: we are certainly not going to find liberation on TikTok. We can find humor, escape, information, thirst traps, recipes, makeup tips, dance routines, distractions, and a voyeuristic view into other people’s lives, but we’re not going to find liberation. So while I am absolutely here for the worldmaking potential of TikTok, especially right now when we are all cut off from so much, I would say that performances like the kind @trevee27 and @nasfromthegram expose the limits of algorithmically driven performance. Once you start getting hundreds of thousands or millions of followers by portraying negative stereotypes of a marginalized group, who are your videos for?

Melissa: Exactly. At whose expense is your TikTok fame? I want to turn back to the discussion of dance to close even though I know we could keep chatting about this forever (maybe this is an idea for a book project, or better yet, a digital humanities one? Watch this space). The best part of TikTok as a dance scholar who focuses on the popular screen is the capacity it has for the creation, circulation, and appreciation of dance moves.

madison: For sure! I think that once we understand the strategies of surveillance and anti-Black technology that undergirds TikTok, we can then move to think about the possibilities the app affords with regards to performance and connecting to others on screen, especially now when so much performance is done on screen.

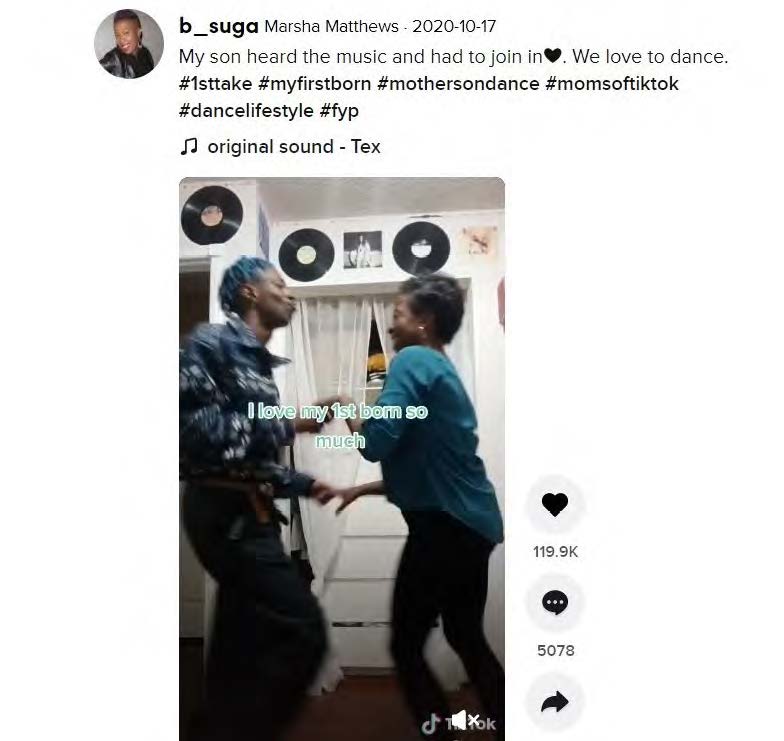

Melissa: I turn to my essay on Janet Jackson to remind us about what dance on screen allows: it is through the ubiquitous availability of such mediated performances that dance on screen becomes (corpo)real and tangible.[28] Intersubjectivity exists in the practice of doing TikTok dance duets, for example. It allows you to dance in real time alongside an already existing TikTok video which you then post and circulate. It becomes a way to dance together, create virtual sociality and for some, to increase their followers. You can also dance in front of a green screen of a well-known performance and show your capacity of imitation, technique and precision (or not). Even though you learn a dance via the screen, you also learn how to embody another body’s technique and style. You practice their corporeal nuances so that you can get the pop of the booty just right, or the timing of the head whip around. You can then improvise and innovate from said choreography. The most popular way to dance on TikTok is to become part of its participatory commons through a particular dance challenge. TikTok dance challenges are what made TikTok such an indispensable escapist activity and space during lockdown. The rules are simple: you watch the original video (e.g., 14-year-old Jalaiah Harmon’s Renegade dance that was appropriated and then went viral on TikTok, the Blinding Lights challenge, 16-year-old Lesley Gonzalez’s Tap in Dance and its subsequent challenge, or the Savage challenge started by Kiera Wilson and endorsed by the song’s rapper Megan Thee Stallion who even posted herself doing it), you learn it, you plan your performance of it, you record and then post it making sure you have the appropriate hashtag to direct viewers to you. Dance challenges are set up to go viral for a period of time. It’s passé now, but I am still obsessed with that #tocotocotochallenge you shared with me over the summer.[29] There is something about seeing the multiple executions of a specific challenge that makes me appreciative of interpretative difference (or commitment to mimicry). These challenges set up TikTok as a space for creative and pedagogical exchange through dance. They bring up the always-present issues around cultural appropriation, choreographic copyright, the racialization of bodies through techniques, and ideas around innovation. Innovation and interpretation are qualities already inherent in social and/or popular dance forms where dance’s reiteration is a prerequisite for its circulation, relationality, and value.[30]Yet, there are multiple ways to have relationality on TikTok with and beyond the dancing. It happens when family members get together to make a TikTok and they take pleasure in the process. It also happens with the uploading of the TikTok on the site and waiting to see who views it, likes it, shares it or copies it. Then, for us, it is sending TikToks to one another based on our shared affinities and what we find fabulous or funny. Sharing TikToks with one another is a rearticulation of our friendship especially during lockdown. Whether it’s teens dancing with their parents and learning #dancechallenge choreographies together, Black family members dancing with one another here, here, and here, or some self-affirmative dancing in front of your bathroom mirror (@dancelife6905) we do whatever it takes to help us endure through this horrific pandemic and the exhausting reminder that we have yet to move past white supremacy and anti-Blackness in the world. Thankfully, we can continue to imagine and create worlds via TikTok where our (Black, Brown, queer) joy can reign supreme.

Screenshot of @b_suga dancing with her son to Solomon Burke’s “Cry To

Me”

Screenshot of

@dancelife6905 doing their morning affirmation dance.

Biographies

Melissa Blanco Borelli is Associate Professor in the School of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is the author of She is Cuba: A Genealogy of the Mulata Body (de la Torre Bueno Book Prize 2016) and the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Dance and the Popular Screen (2014). You can follow her on TiKTok @athleticacademic.

Email: mblanco@umd.edu

madison moore is an artist-scholar, DJ and teaches queer studies in the Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. madison is the author ofFabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), a cultural analysis of fabulousness. madison is currently writing a book about ephemeral traces, rave scenes and queer of color undergrounds. Follow madison on Instagram @madisonmooreonline

Email: mamoore2@vcu.edu

Website: www.madisonmooreonline.com

References

Bailey, Moya. Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance. New York: New York University Press, 2021.

Bench, Harmony. Perpetual

Motion: Dance, Digital Cultures, and the Common. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvxw3p32

Blanco Borelli, Melissa. “Dancing in Music Videos, or How I

learned to dance like Janet… Miss Jackson.” The

International Journal of Screendance 2 (2012). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v2i0.6937

Benjamin, Ruha. Race

After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA:

Polity Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz162

Foster, Susan Leigh. “Why Is There Always Energy for

Dancing?” Dance Research Journal 48.3

(2016): 12-26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767716000383

---. Valuing Dance:

Commodities and Gifts in Motion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190933975.001.0001

Harris, Tristan. “How Technology Hijacks People’s Minds -- From a Magician and Google’s Design Ethicist.” The Observer. 1 June 2016. https://observer.com/2016/06/how-technology-hijacks-peoples-minds%E2%80%8A-%E2%80%8Afrom-a-magician-and-googles-design-ethicist/

Hernandez, Jillian. Aesthetics

of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment Durham: Duke

University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478012634

Lang, Cady. “Best TikTok Dances of 2020 So Far.” Time Magazine. https://time.com/5880779/best-tiktok-dances-2020/

McGlotten, Shaka. “Streaking.” TDR: The Drama Review 63.4 (Winter 2019): 152-171. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram_a_00881

Morrison, Elise, Tavia Nyong’o, and Joseph Roach.

“Algorithms and Performance: An Introduction.” TDR: The Drama Review 63.4 (Winter 2019): 8-13. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram_a_00871

Muse, John. Microdramas: Crucibles for Theatre and Time. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9380984

Ngai, Sianne. “Theory of the Gimmick.” Critical Inquiry 43 (Winter 2017): 466-505. https://doi.org/10.1086/689672

Nobel, Safiya. Algorithms

of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. Durham: Duke University

Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9w5

Roach, Joseph. Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Swanson, Anna, David McCabe, and Erin Griffiths. “Trump Officially Orders TikTok Owners to Divest.” New York Times. 14 August 2020. Accessed 14 January 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/business/tiktok-trump-bytedance-order.html

Taylor, Diana. Performance. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Ybarra-Frausto,

Tomás. Rasquachismo: A Chicano

Sensibility. School by the River Press, 1989.

Notes

[1] McGlotten, “Streaking,” 160

[2] Morrison, Nyong’o, and Roach, “Algorithms and

Performance,” 10.

[3] Thank you to Elena Benthaus for drawing our attention to Ngai’s essay on the gimmick.

[4] Ngai, “Theory of the Gimmick,” 469.

[5] Taylor, 17.

[6] Benjamin, Race After

Technology, 17; Noble, Algorithms of

Oppression, 4.

[7] Browne, Dark

Matters, 114.

[8] In August 2020, the Trump Administration issued an Executive Order asking the Chinese owners of TikTok, ByteDance, to divest from its American assets for fear of privacy and national security violations. They were given a 45-day deadline. ByteDance currently continues negotiations to be sold to Oracle and Walmart. See article by Laura Kolodny “President Trump Orders Bytedance to Divest from US TikTok” CNBC, 14 Aug. 2020. Accessed 3 May 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/14/president-trump-orders-bytedance-to-divest-from-its-us-tiktok-business-within-90-days.html

[9] Muse, Microdramas,

2.

[10] Surrogation is a term taken from the work of theatre historian Joseph Roach in Cities of the Dead.

[11] Bench, Perpetual

Motion, 9.

[12] Ibid. 4.

[13] McGlotten, 154.

[14] Harris, “How Technology Hijacks.”

[15]

Rasquache is a term used to describe

a particular working class Chicano sensibility related to food, dress, words,

aesthetics and structures of feeling. The term emerged in the work of Tomás

Ybarra-Frausto, Rasquachismo.

[16] Ngai, 504.

[17]

Bird Martinez was unfortunately the victim of a serious crime and is now faced

with possible quadriplegia. Her family has set up a GoFundMe account and we

list it here in case you would like to contribute funds to help defray the

costs of her housing and medical bills: https://www.gofundme.com/f/99quvv-help-with-medical-and-housing-bills

[18] Hernandez, Aesthetics of Excess, 6-7.

[19] Benjamin, 160.

[20] Hernandez, 11.

[21] Ibid.

[22]

Taylor, Performance, 26.

[23] Foster, “Why Is

There Always Energy For Dancing?” 15.

[24] “Tehching Hsieh: One Year Performance 1980–1981,” Uploaded 30 April 2014. Accessed 8 Jan. 2021 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvebnkjwTeU

[25] This term was coined by Moya Bailey to explain the intersection of misogyny and race on Black women’s lives. A full-length book is forthcoming entitled Misogynoir Transformed.

[26] Jordan Ealey via text message 18 November 2020.

[27] Noble,10.

[28] Blanco Borelli, “Dancing in Music Videos.”

[29]

Here are three examples of the #tocotocotochallenge: https://vm.tiktok.com/ZScAqXnD/ ; https://vm.tiktok.com/ZScAQrMn/ ; and https://vm.tiktok.com/ZScAg1o7/. In this challenge, the

idea is to successfully walk rhythmically and in sync to the music while

wearing very high heels and changing positions from forward facing, walking

sideways, walking forwards with back turned in opposite direction and then

turning to walk forwards again. It requires multiple skills: upright torso and

ab strength, ability to walk comfortably in 5+ inch heels, and rhythmic and

spatial awareness.

[30] Here, I am thinking about what Susan Foster articulates in Valuing Dance: “dance’s actions, riddled with power, suffused with history and memory, constantly create, renew, and reaffirm connections between and among dancers and, when present, their teachers, choreographers, or viewers. Dancing combines, segregates, bonds, and excludes, but in any of these acts, it brings people into relation” (33).