The Dance-In and the Re/production of White Corporeality

Anthea Kraut, University of California, Riverside

Abstract

This essay examines the figure of the “dance-in,” a stand-in who dances in place of a star prior to filming, focusing on two women who acted as surrogates and dance coaches for the mid-twentieth century white film star Betty Grable: a white woman named Angie Blue and an African American woman named Marie Bryant. Bringing together film studies theories of indexicality, performance studies theories of surrogation, and critical race theories of flesh and body, I argue that the dance-in helps expose how the fiction of white corporeality as a bounded and autonomous mode of being is maintained.

Keywords: dance-in, white corporeality, surrogation, indexicality, Betty Grable, Angie Blue, Marie Bryant

In 1935, the Los Angeles Times ran a seventy-word article under the headline “Dance Stand-In,” explaining a new phenomenon in Hollywood:

“Stand-ins,” persons who take the places of stars while the cameras are being properly focused, have become an accepted fact around the studio sets. Now comes Shirley Temple, youngest star of them all, with a new kind of stand-in – a dance stand-in. Marilyn Harper, one of the Meglin Kiddies, is Shirley’s dance stand-in. Marilyn goes through all the terpsichorean motions for Shirley until she is ready to take her place.1

The need for “dance stand-ins,” sometimes referred to as “dance-ins,” coincided with the rise of the film musical and the increased occurrence of dance in film, ushered in by the advent of sound in Hollywood.2 Key to the operation of movie-making but seldom heralded, dance-ins joined the ranks of other “Hollywood unknowns” – extras, stand-ins, doubles – who were “relegated to the margins of the film industry” and almost never credited.3

In her compelling article “Missing Persons and Bodies of Evidence,” Ann Chisholm traces the emergence of stand-ins, whose work saved the energies and labor of stars, to the film industry’s growing reliance on rehearsals and its move “toward efficiency and replication” in the 1920s.4 Her focus is on the paradoxical ways stand-ins and their close relative, body doubles, have been crucial to the production of film and film stars even as they are continually disavowed or disparaged as “second-rate physical cop[ies].” Dwelling on this contradiction, Chisholm highlights the ambiguities and slippages generated by these “supplementary bodies,” who are simultaneously marginal and vital, alternate between presence and absence, and are both in excess of and substitutes for stars.5

Unlike a stand-in, the body (or body parts) of a double appears on screen, masquerading as that of the star. The use of doubles accordingly necessitates some sleight-of-hand film editing designed to trick spectators.6 In the case of dance doubles,7 this deception can become controversial. 2011, for example, saw a scandal erupt when American Ballet Theater’s Sarah Lane spoke openly about her role as Oscar-winning actress Natalie Portman’s double in the 2010 film Black Swan, exposing the “façade” propagated by Foxlight Searchlight that Portman did ninety percent of her own dancing.8 Because the double creates questions about whose body we are seeing on screen, it destabilizes the assumed correspondence between a star’s on-screen image and her off-screen corporeality. In film studies, this destabilization is part of a larger issue that has been described as the “politics of indexicality,” which I will return to below.

If stand-ins’ and dance-ins’ lack of on-screen visibility9 means they don’t require the same kind of cinematic subterfuge, they are no less capable of producing slippages. This is evident in the very language of the LA Times’s announcement of the dance stand-in’s emergence. Take the last sentence of the article:10 “Marilyn goes through all the terpsichorean motions for Shirley until she is ready to take her place.” The “she” here is clearly Temple, but whose place is Temple taking? That of Harper, her dance-in? Or her own (rightful) place as star? This imprecision allows us to read “her” in a double sense: when the star takes her place before the camera, she is taking both her own and her dance-in’s place. To belabor this even further, recall that the first sentence in the article defines stand-ins as those who take the place of stars. Both stars and stand-ins, then, perform the action of taking an/other’s place, and, in the case of dance-ins, this two-way place-taking precedes and determines any dancing we ultimately see on screen.

Even if coincidental, the uncertain referentiality of pronouns in the Times piece might be seen as symptomatic of the dance-in’s ambiguity more broadly – her position, that is, betwixt and between live performance and film. Put simply, the dance-in has a peculiar ontological status. Subject to the filmic apparatus without necessarily ever appearing on screen, dance-ins blur the lines, or exist at the nexus, between the live and the technologically mediated. As such, they should be regarded as interstitial, intermedial, and interdisciplinary figures, qualities that others have argued are inherent to screendance itself.11 And it is precisely this liminal disciplinary status that makes the dance-in such a productive site for screendance.

As Sherril Dodds, Harmony Bench, and Douglas Rosenberg have all shown, screendance is a particularly rich field for interrogations of the body. In Dodds’s influential formulation, “the presentation of a ‘live body’ is unavoidably transformed when it becomes a ‘screen body.’”12 During this process of what Rosenberg calls “recorporealization,” screendance has the potential to shift our understanding of bodies, including by “unmooring” notions of the body “from somatic and corporeal absolutes.”13 Scholars of digital media have been especially attuned to the ways the post-film era “has irrevocably shifted our sense of the real body.”14 Because dance-ins exist at the critical juncture between the live and the screen, they encourage us to think more expansively about recorporealization and to complicate our approaches to live and screen bodies alike.

This essay pursues the implications of the dance-in through a case study of the white 1940s Hollywood icon Betty Grable and two women who danced in her place. Grable’s whiteness is central rather than incidental to my investigation, for her dependence on “supplementary bodies” challenges the ostensible singularity and integrity of the star’s white body.15 Taking a “behind the screens” approach16 to Grable’s image, I hope to demonstrate that dance-ins are important to screendance not only for the ways they “push…at the boundaries of…traditionally wrought disciplines”17 but also for the ways they push at the boundaries that mark white corporeality as a privileged mode of being.

To make that case, I first place into dialogue concepts from screendance and film studies, dance and performance studies, and critical race theory. Given the acts of substitution that define her work, the dance-in lends herself to analysis in terms of performance studies notions of surrogation and doubling. And given the corporeal slippages that tend to accompany those substitutions, the dance-in is well situated to contribute to debates in dance studies, performance studies, and critical race studies about the status and constructedness of “the body” as an apparently autonomous entity. These debates in turn intersect with film studies concerns about the in/stability of the film image as an “index” of a pre-filmic body.

After laying this theoretical groundwork, I then examine the specific inter-corporeal entanglements between Grable’s on-screen dancing body and a white woman named Angie Blue, who served as her official dance-in. Dance-ins, as will become clear, share a familial resemblance not only with extras, stand-ins, and body doubles but also with the choreographers, choreographers’ assistants, and dance instructors who work off camera to shape stars’ bodies, usually without credit.18 Considering how steeped Hollywood dancing was in Africanist influences,19 it is perhaps inevitable that tracing Grable’s relationship to her white dance-in winds up uncovering the star’s genealogical links to dancers of color as well. In Grable’s case, I will show, an African American dance coach named Marie Bryant functioned in ways that were similar to Blue; both women helped recorporealize Grable’s body through a series of power-laden exchanges. Together, Blue and Bryant provide a window onto the larger racialized and gendered ecology of unseen dance artists on which the white star’s filmic image rests. Ultimately, I hope to show, the invisibility that was part of the conditions of re/producing the star’s white dancing body on screen cannot be disentangled from the invisibility that was part of the conditions of re/producing white supremacy.

Whiteness, Corporeality, and Indexicality

Before peeling back the layers of Grable’s on-screen corporeality, it is necessary to double back to the fact that, according to the LA Times article, Shirley Temple was among the first to benefit from a dancing stand-in. The most popular child star of the 1930s, Temple was the personification of innocent white femininity.20 That the dance-in emerged in service of Temple encourages us to ask how this supplemental body functioned as a technology of gendered whiteness.21 Just as Teresa De Lauretis has argued that the cinematic apparatus is part of the technology of gender – that gender is “not a property of bodies” but the “product of various social technologies”22 – so too I want to explore how the dance-in serves as a technology of race as it intersects with gender.

It is by now widely accepted that whiteness is constructed and that, in the U.S., film has played an outsized role in framing whiteness as a universal norm and aesthetic ideal.23 Appropriately, then, film scholars have been at the forefront of theorizing whiteness. While Michael Rogin, for example, has pointed to the donning and removing of blackface as a crucial mode of producing whiteness on screen, Richard Dyer has exposed how movie lighting creates “a look that assumes, privileges and constructs an image of white people,” and how idealized images of white women in film are fashioned through lighting techniques that make them appear to glow.24 It is significant in this regard that one of stand-ins’ primary functions was to allow cinematographers to determine the proper lighting for the star and that they were thus required to approximate the “height, weight, and coloring” of the star.25 Although little is known about Marilyn Harper, Temple’s dance stand-in,26 both she and Temple got their start with Meglin’s Kiddies, a Los Angeles-based dance studio (actually a collection of studios) that groomed white children for show business. An online clip of a 1933 vaudeville act featuring “Meglin’s Famous Kiddies” shows a sea of white children tap dancing and performing acrobatic tricks.27 An entire industry stood ready to supply dancers who could visually match Temple on film.28

But the white stand-in who dances in place of a white star does more than just resemble that star, and her dance labor offers insight into how whiteness is re/produced in ways that exceed the replication of white physical appearance or the performance of blackface. One way of understanding that reproduction is as an act of surrogation. I invoke here performance studies scholar Joseph Roach’s influential theorization of performance as “the process of trying out various candidates in different situations – the doomed search for originals by continuously auditioning stand-ins.”29 For Roach, surrogation describes the re-production of the social fabric in a broad sense, “the enactment of cultural memory by substitution” as “survivors attempt to fit satisfactory alternates” into “the cavities created by loss through death or other forms of departure.”30 If one of the primary functions and effects of mainstream film in the U.S. has been to uphold the dominance of the white social fabric, then we might approach the reproduction of idealized white femininity via the dance-in as surrogation on both a macro- and micro-scale.

Roach’s notion of surrogation has not been without critique. Performance studies scholar Diana Taylor, for one, argues that because as a model, surrogation depends on an assertion of cultural continuity enabled by the erasure of antecedents, notions of performance as “doubling, replication, and proliferation” are more apt.31 My understanding of the dance-in, however, is that she blurs the lines between surrogation and doubling, as well as those between the original and the copy. As I hope to show, even while the dance-in’s labor must be invisibilized32 in order for the star to assume her rightful place, the stand-in’s dancing, at least in some cases, bleeds into and re-shapes the body of the star. In other words, to draw together concepts from performance studies and screendance studies, surrogation begets recorporealization. Recalling the language of the LA Times piece, the white “her” that we finally see on screen should be approached not as a singular “her” but as an assemblage of multiple bodies’ terpsichorean motions.

In approaching “her” as a multiplicity, I engage work across several fields that has increasingly placed pressure on the notion of the bounded, individuated body. While the camera’s ability to “multipl[y] the self on screen” makes corporeal proliferation a matter of course from a screendance perspective,33 the dance-in’s liminal status makes it worth considering challenges to corporeal discreteness from scholars not explicitly concerned with technological mediation. Philosophers like Erin Manning and Jose Gil, for example, have theorized the body as always relational, always “more than one.” “‘The body’ is a misnomer,” Manning writes. “Nothing so stable, so certain of itself ever survives the complexity of worlding.” She approaches the body instead as “a transition point” and “the amalgamation of a series of tendencies and proclivities.”34

Critical race theorists, meanwhile, have long submitted “the body” to incisive critique. Of particular note here is Hortense Spillers’s 1987 essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” which takes on the 1960s Moynihan Report and its problematic casting of the “Negro family” as pathological due to the prevalence of female-led households. Spillers insists that we approach the intersection of gender and race through a different genealogical lens: the “socio-political order of the New World” and the “willful and violent…severing of the captive body from its motive will” for capitalist purposes.35 For the enslaved, the resulting “American grammar” of reproduction both disrupted the patriarchal order (since children born to enslaved women inherited the condition of their mother) and evacuated “kinship” of its meaning “since it can be invaded at any given and arbitrary moment by the property relations.”36

In one of Spillers’ most frequently cited passages, she makes a distinction between “body” and “flesh” and suggests that this distinction is “the central one between captive and liberated subject-positions.” “In that sense,” she proposes, “before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh,’ that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconography.”37 In his study of the aesthetic practice of Black Pentecostal breath, Ashon Crawley interprets Spillers to mean that “Flesh designates a borderless, discontinuous object, previous to its being sexed, previous to its being raced. As Spillers would have it, the ‘body’ that comes after the flesh is produced through rhetoric, through discourse.” This “body,” he offers, “is a categorical coherence, it is a theological-philosophical concept of enclosure, a grammar and logic producing something like bodily integrity.”38 Whether or not we subscribe to the notion of flesh as a pre-discursive realm, Spillers’s differentiation of flesh and body resonates in provocative ways with approaches to corporeality in dance studies.39 Her ideas are also a potent reminder that, when we take “the body” as self-evident, we fail to see how racial projects have done their work through the disparate ways they fashion “bodies” out of flesh.

To wit, Spillers’ insights have a direct bearing on understandings of white embodiment.40 Taking a cue from Spillers, for example, Eva Cherniavsky has proposed that we approach race as “the radically uneven capacity of bodies to serve as the shell (the organic container) of the subjects they embody.”41 In her formulation, one of the key privileges of whiteness is “incorporated embodiment,” the “articulation of bodily form for the subject at risk of dispersal.”42 The fiction of bodily integrity, in other words, has been a site of racialization and an instrument of white supremacy, protecting whites from the incursions of capital that defined the terms of African Americans’ entry into the U.S.

These critical race approaches to body and flesh are relevant to my examination of Hollywood dance-ins in at least two ways. First, to the extent that dance-ins helped construct seemingly coherent images of white dancing film stars, they provide another avenue through which to understand how white embodiment comes to assume its idealized and privileged form. That is, the unseen and distributed work that it takes to re/produce white dancing bodies for the screen may serve as a microcosm of the construction of white corporeality more broadly.43 Second and relatedly, the slippage between flesh and body that Spillers highlights echoes a recurrent concern of media theorists: the slippage between on-screen image and off-screen referent.44 As film scholars like Kara Keeling and Mary Ann Doane have addressed, the shift from celluloid to digital film has created a certain anxiety, or “identity crisis,” around the question of indexicality.45 In Keeling’s succinct explanation of the crisis, “The filmic regime of the image claims to be an index of that reality, thereby encouraging identification between the image and its presumed referent, while the digital complicates that schema of identification by calling into question the very notion of a ‘prefilmic reality’ to which the digital image might lay claim.”46 Yet as Keeling goes on to say, even a glancing familiarity with representations of blackness in cinema gives the lie to the idea of film as an index of reality. “Where images of blacks are concerned,” she argues, “cinema’s indexical identity has always been in crisis or, at least, it has always been interrogated and undermined.”47

Keeling’s observation helps cast my study of Hollywood dance-ins in the middle of the twentieth century as a return to a historical moment in which white bodies on film were still presumed to have stable referents.48 My premise is that, even in a pre-digital era, the relationship between on-screen image and off-screen materialities was far more complicated than it appeared. Keeling’s argument, it is worth noting, rests on black spectators’ ability to recognize the fallacy of screen images of black bodies.49 Conversely, images of white dancing stars from the so-called Golden Age of the Hollywood musical50 continue to be regarded as “truthful” representations of their unique physicalities. Scholar Erin Brannigan, for instance, has argued not only that (white) stars’ bodies were the “film musical’s primary, unifying element” but also that those images were determined primarily by stars’ “corporeal specificity,” which she terms their “gestural idiolect or idiogest.”51 I have argued elsewhere for the concept of corporeal signature52 and certainly do not mean to refute the idea that dancers have distinctive ways of moving. Rather, I’m interested in investigating what and whom the notion that the filmic image of a dancing star is a direct reflection of their “idiogest” might obscure. Using the construction of Betty Grable’s white dancing body as a test case, and building on the work of the above theorists, I ask whose flesh Grable’s iconically white and seemingly coherent body was simultaneously indexing and concealing.

“Doing Angie”

In the 1940s, the actress, singer, and dancer Betty Grable (1916-1973) was a reliable box-office draw in Twentieth Century Fox Technicolor musicals, the highest-paid female star (and therefore the highest paid woman in the U.S.),53 and the reigning “pin-up girl,” whose photographic image was distributed to five million servicemen during World War II. Her legs reportedly insured for over a million dollars with Lloyds of London, the “blonde and snow-white” Grable epitomized white womanhood and “all things American.”54 Reminding us that “the war in the Pacific was a race war,” historian Robert Westbrook cites a Time magazine report that “soldiers preferred Grable to other [less blonde] pin-ups ‘in direct ratio to their remoteness from civilization.’” Grable’s “obvious whiteness,” Westbrook concludes, made her the “superior image of American womanhood.”55

Throughout the 1940s, a white woman named Angela (Angie) Blue (1914-2004) served as Grable’s dance-in. An uncredited dancer in a number of 1930s films and later under contract as a dance director at Twentieth Century Fox Studios, Blue auditioned for a part as a chorus girl in the 1934 Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers film The Gay Divorcee, which led to an encounter with Hermes Pan, the prolific white Hollywood choreographer best known for his work with Astaire.56 Pan considered Blue a “marvelous dancer” with a “quirky gaminesque quality,” and by 1937, she became his assistant.57 Particularly useful to Pan, Blue was “pliable”: as he later recalled, “I could grab her by the hand and throw her into position and she’d just do it…I could turn her around and whip her like a piece of clay and she would fall into things. She was like putty.”58 With Spillers’ flesh/body distinction in mind, we might say that, for Pan, Blue was all flesh, and that her lack of “categorical coherence” was what gave her value as a choreographer’s assistant. When Pan began creating choreography for Grable in 1941, the blonde Blue was a natural choice to serve as Grable’s dance-in, and the two women developed a close friendship that lasted for years.59

Because Grable preferred not to be involved in the choreographic process, Pan relied on Blue to help work out Grable’s routines. “Betty Grable hated to rehearse and admitted it,” Pan told biographer John Franceschina. “She’d say, ‘Oh, just show it to me and I’ll do it.’”60 Consequently, “working with Betty Grable involved Pan and Angie Blue creating complete routines ahead of time and teaching them to her, much in the same way they might work with a dancing chorus.”61 Though Grable trained in dance from an early age and danced in nearly all of her films, assessments of her dancing were decidedly mixed. “She really was not a great tap dancer,” Pan once claimed, “and she couldn’t do great ballet. But she could move, and she had very beautiful legs, and…[h]er color was beautiful.”62 Never one to inflate her abilities, Grable maintained that she was only an average dancer, and she was content to just do “what she was told.”63

For Grable, learning choreography was thus a process of mimicking Blue. Just as Pan stood in for Ginger Rogers when he worked out routines with Fred Astaire, Blue would “be Grable” when she and Pan worked out routines for Grable. Once the choreography was set, “Betty Grable was…instructed by Pan to ‘do Angie.’” In fact, a 1991 article about Pan reported that “the famous Grable itty-bitty walk as well as the bathing suit, hands on hips, over the shoulder pin-up of the 1940s was simply her ‘doing Angie.’”64

This is a rather remarkable revelation in its inversion of the presumed relationship between star/original and stand-in/copy. Among the unofficial “rules” for stand-ins listed in a 1938 article about Bette Davis’s stand-in, Sally Sage, was the following: “Study your star. Be able to copy her walk and her stance.”65 In Grable’s case, by contrast, the star’s job was to study and imitate her proxy. There is, then, both an exactness and a muddiness to performance-as-surrogation in this case: because Grable’s performance depends quite literally on “trying out” the physicality of her stand-in, it is not clear who is the surrogate for whom. Standing in for her own dance-in, Grable inserts her body into the choreographic score Blue helped establish, even as Blue presumably rehearses that score as if she were Grable.

The claim that Grable’s over-the-shoulder pose was an impersonation of Blue is especially striking, for this was the shot of Grable that was distributed as a pin-up poster to American servicemen across the globe as an emblem of white femininity worth protecting. Grable’s most Grable-like image, that is, was the result of the star reproducing the corporeality of her uncredited dance-in. On one hand, this fact underscores the constructedness of whiteness and supports arguments like film scholar Sean Redmond’s that whiteness only exists as “a trace, an imprint or an echo of itself.” “Whiteness is a photograph of itself,” he forcefully asserts.66 On the other hand, the recognition that this most iconic image of Grable bears the traces of Blue’s body (or is it her flesh?) highlights the indexical ambiguity that inheres in whiteness-as-photograph. Indeed, parsing whom the “her” in the photo references is far from straightforward.67 If it would seem to matter very much that the photo indexes Grable’s insured flesh, does it matter less that it also indexes Blue’s corporeal shape? And lest we are tempted to locate the traces of Blue’s presence in the silhouettes that also appear in the photo – a literalization of stand-ins’ role as “star’s shadows”68 – those shadows, as we shall see, index additional unseen flesh. Modifying Redmond, we might say that whiteness is a photograph of multiple corporealities that only appear to cohere as the singularity of “itself.”

The Other Betty

As I have tried to suggest, attention to the role of the dance-in is useful precisely insofar as it muddies the question of whose bodies (or flesh) a star might be indexing. And because, in contrast to doubles, dance-ins don’t typically take stars’ place on screen, they invite us to think more broadly about the off-screen acts of surrogation and recorporealization – the emulating, the doubling, the blurring of physicalities – that are concealed behind bodies that seem self-referential and coherent. Rather than reify Blue as the sole pre-filmic source or “true” index of Grable’s on-screen dancing body, in the remainder of this essay I want to situate both “hers” (Blue and Grable) within a longer chain of inter-racial, inter-corporeal reproductions.

Of course film choreographers, who were predominantly white men in the Golden Age of the Hollywood musical, were major players in the inter-corporeal exchanges that shaped on-screen bodies.69 But even if Pan’s characterization of Blue as “putty”-like positions him as the sculptor of her flesh, to take his dancing body as a point of origin would be to overlook the African American sources that undergirded the formation of his corporeality. A 1991 profile of Pan in The Dancing Times opens with the following:

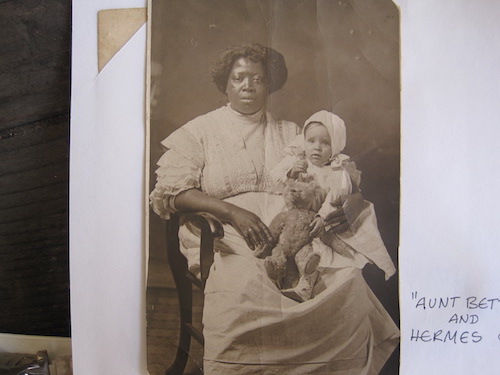

In 1915, when Hermes Pan was six years old, the family mammy, a big black woman who was called Aunt Betty, took the boy home with her one night to her apartment in the black ghetto of Nashville known, as it was in many cities in the American South, as Black Bottom. It was there that the child was first exposed to what was called “gut-bucket” jazz and the shuffles and foot-slapping dancing of the local black Americans. His reaction was an exhilaration which he recalled seventy years later, his eyes still lighting up with joy at the memory, as nothing short of “sensual.” That was Pan’s first exposure to what he knew as “dance.”70

This is by now a familiar story in American dance, proving once again Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s argument about the Africanist influences on the development of all manner of U.S. dance genres.71 But the presence of a “mammy” in the narrative of Pan’s dance origins adds another layer to the story. A photograph of an infant Pan seated on the lap of his “Aunt” Betty, likely taken around 1910, appears in Franceschina’s biography of Pan.72 These photographic and recollected traces of Aunt Betty are stark reminders of the centrality of another kind of surrogation to U.S. racial formations: the long history of black women serving as surrogate mothers for white children. They also return us again to Spillers, who begins her essay citing the litany of ways that black women in the U.S. have been marked, including as “Aunty.” Such “confounded identities,” she argues, construct bodily tropes out of black flesh and deprive black women of individualized personhood.73

In her critical analysis of shifting depictions of the mammy figure in U.S. culture, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders writes that the “mammy’s body serves as a tendon between the races, connecting the muscle of African American slave labor with the skeletal power structure of white southern aristocracy.”74 In like manner, Aunt Betty serves as the connective tissue between black surrogate motherhood and the structures that enabled white reproductions of African American dance. For, as the anecdote about Pan’s exposure to jazz dance goes on to note, Pan’s first dance lesson entailed “imitating the steps” he and his sister “learned from the family’s black houseboy, Tommy,” who, according to some reports, was Betty’s biological son.75 Pan’s case thus exemplifies the collision of multiple kinds of surrogation and reproduction. This collision makes it possible to draw a line between the two Betty’s: the Greek American Pan family’s black domestic employee (not afforded a last name) and the white film star, who, in “doing Angie,” was repeating a pattern of imitation with cross-racial antecedents. Looked at through this lens, Grable’s famous pin-up posture – arms akimbo, leaning into one hip, shoulders twisted – becomes not only a coy, come-hither pose but an asymmetrical, Africanist one.76 Awareness of Pan’s Aunt Betty, meanwhile, encourages us to train our eyes on the flesh of other black surrogates who were lurking in the shadows – and indexed by the on-screen images – of white film stars.

Marie Bryant and Betty’s Buns

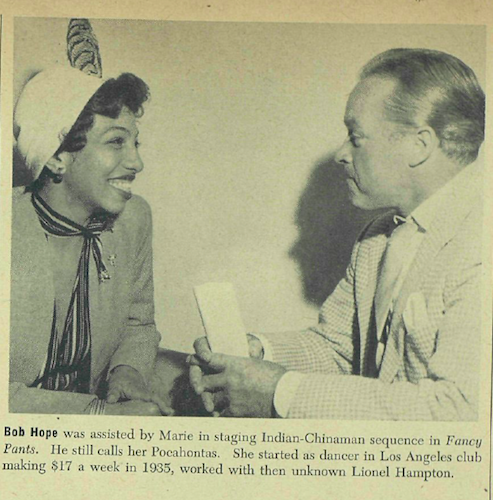

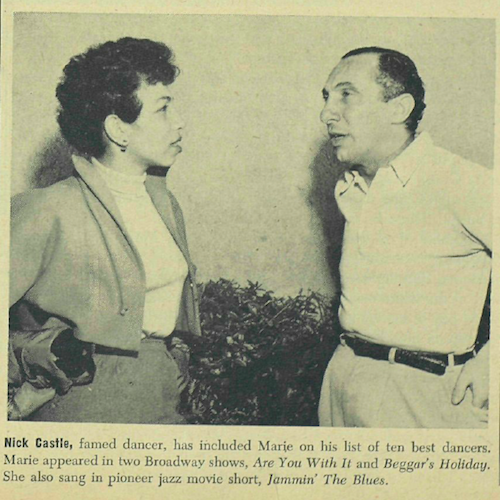

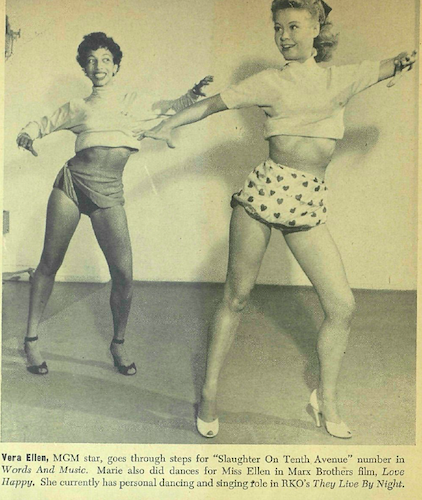

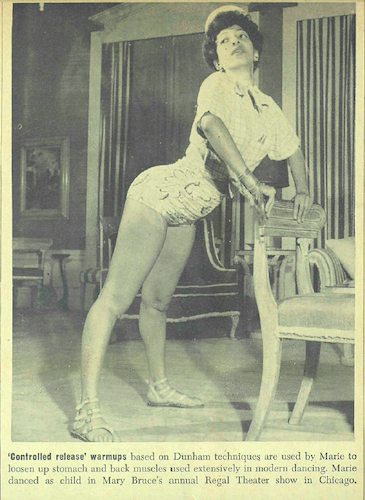

A little more digging reveals that, as Grable’s career went on, her reproductions of black corporealities became increasingly direct. A three-part 1950 article in Ebony magazine discloses the pivotal behind-the-screen role played by the African American Marie Bryant (1919-1978) in Grable’s later dance performances. A supremely talented dancer, as well as a singer and choreographer, Bryant toured with Duke Ellington, danced in the chorus of some Lena Horne films, and taught at dance schools run by Katherine Dunham and Eugene Loring.77 Ellington, Gene Kelly, and Hollywood dance director Nick Castle separately described her as one of the best dancers they had ever seen.78 Evidence of her skill survives on screen, such as her appearance in an uncredited role with Harold Nicholas in the 1944 film Carolina Blues.79

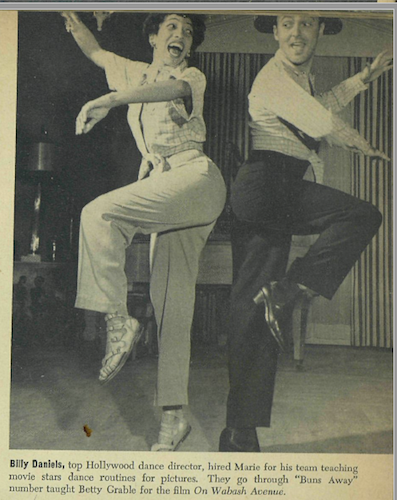

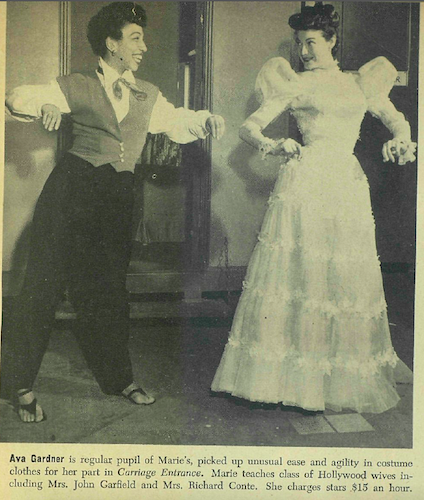

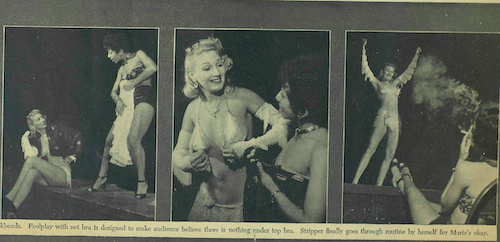

Proclaiming her the “first Negro to crack the technical side of Hollywood with the official title of assistant dance director,” the feature in Ebony documents Bryant’s work teaching dance routines to white Hollywood stars like Grable, Vera Ellen, Paulette Goddard, Ava Gardner, and Bob Hope, as well as teaching “more art and less come-on” to burlesque dancers. Bryant credited Gene Kelly with being the first to hire her to coach film performers. Grable and her husband evidently discovered Bryant when she was headlining at the Los Angeles Cotton Club; Grable subsequently asked Bryant to help stage dances for the 1950 film Wabash Avenue, whose choreography is credited to the white dance director Billy Daniel. Bryant also worked as an assistant dance director to Jack Cole on Grable’s 1951 film Meet Me After the Show.80

The third part of the feature in Ebony explains the nature of Bryant’s work as assistant to Billy Daniel: “Marie, Daniels [sic] and his other assistant, Frances Grant, report on a picture, create the choreography for the stars. Then the three of them block out the steps, acting in place of the stars, who stand by, watching, then learning the dance routines.”81 As described here, the relationship between choreographers and stars bears a striking resemblance to that between dance-ins and stars: dance directors perform terpsichorean motions until stars are ready to take their place. For anyone who has ever learned choreography, this description of observation, imitation, and place-swapping may well fall into the category of the obvious. But in spelling it out in this manner, Ebony calls attention to the surrogation that choreographic transmission – the act of transferring movement across flesh – entails. Choreographers perform as stars’ surrogates; stars insert their bodies into places carved out by choreographers. Put another way, choreographers act as dance-ins, just as, in the case of Blue, dance-ins function as choreographers.

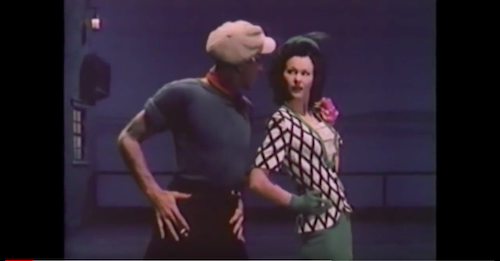

The Ebony spread also includes a series of photos of Bryant and the various stars with whom she worked. Among these are images of Bryant embracing Gene Kelly, in conversation with the actor Bob Hope and choreographer Nick Castle, and in rehearsal with Vera Ellen, Ava Gardner, and Billy Daniel. An additional three shots show white female stars in films on which Bryant coached them. There are also six photos of Bryant teaching a routine to a white burlesque dancer, and one of Bryant alone, demonstrating her “controlled release” technique of warming up the body, which she described as “finding the natural line of each body and the favorite ways it likes to move about – then controlling these movements.”82

These images serve as powerful visual evidence of Bryant’s position within Hollywood’s dance economy. In the sequence with the burlesque dancer, Bryant is clearly the authoritative, “demonstrative body,”83 giving movement to, instructing, and observing her pupil. The other photos are particularly fascinating because of the ways the black Bryant and the white Hollywood stars double one another. In the action shots, Vera Ellen, Ava Gardner, and Billy Daniel either mirror or echo Bryant’s physicality almost exactly, even if they don’t quite achieve her angularity. And in the still shots, Bryant’s body language is virtually identical to that of Kelly, Hope, and Castle. What all of this doubling registers is transmission: the exchange of smiles, of thoughtful conversation, and, most crucially, of movement, between black body and white.

But these photographs are as much documents of surrogation as of doubling and exchange. That is, they teach us to see Bryant’s presence where she is ostensibly absent and, in turn, to read white star bodies not as autonomous and self-contained but as relational, malleable, and indexical of black corporeality. This is especially clear in the image of Bryant partnering Daniel: in the film version of the scene pictured, “Buns Away” from Wabash Avenue, Grable has taken Bryant’s place. But it is also true for the images in which Bryant does not (visually) appear at all. Even in the absence of credit or on-screen visibility, the article and photographs suggest, white female stars’ dancing bodies refer back to Bryant. Here, again, we may see whiteness as photograph-like insofar as it is a document of absent presences. But what whiteness-as-photograph depicts is not “itself” but an assemblage of physicalities.

According to Daniel in the Ebony feature, one of Grable’s body parts in particular bore the traces of Bryant’s training efforts. “During work at 20th,” he told the magazine, “Marie was teaching Betty Grable a hard routine. After a couple of tries, Betty started to do such a fine dance that Marie suddenly yelled at her, ‘That’s it, Betty! Those buns are great! Oh those buns!’”84 At a time when the Arthur Murray Dance School warned (white) ballroom dancers not to emphasize the backside, and amid a legacy of white objectification of black female bottoms, Bryant reverses the white gaze as she works to cultivate an explicitly Africanist aesthetic in Grable.85 The same flesh that comprised part of Grable’s most distinguishable and valuable feature was thus no less inter-corporeal than the rest of her terpsichorean motions.

So, what to make of all this? What are the implications of understanding doubling, surrogation, and recorporealization as part of the technology that produced Grable’s on-screen white femininity, and what difference does it make to see her iconic white femininity as indexical of both white and black dance-ins and coaches? To start with, knowledge of these off-screen acts of surrogation can help us read dance on screen differently. Not only can we learn to perceive Grable’s dancing body as indexical of something other than “herself,” but we can also learn to detect signs of the work required to uphold the façade of the white body’s boundedness and singularity. As Roach reminds us, surrogation is an operation that often generates anxiety and a complicated oscillation between remembering and forgetting. One way this anxiety can materialize in performance is in the form of a “momentary self-consciousness,” in which an “alien double…appear[s] in memory only to disappear.”86

We should not be surprised, then, that both Blue and Bryant appear fleetingly onscreen with Grable. Blue, of course, was a chorus girl in a number of Grable’s films, but it is difficult if not impossible to single her out among the background dancers. In the 1944 film Pin-Up Girl, however, Blue has a featured though uncredited role dancing with choreographer Hermes Pan. In what has been described as an “apache blues number”87 (although they are not technically dancing an apache dance), Blue, wearing a brunette wig – presumably to distinguish her from Grable – saunters on the stage-within-the-film and begins a seductive dance with Pan, before Grable begins to sing from a balcony, sending Blue off stage left. We might say that the footage momentarily remembers Blue as Grable’s surrogate so that we can forget that Grable is also Blue’s surrogate insofar as she is “doing Angie.” That Grable is less of a dancer than Blue – her performance is competent but somewhat stiff – only highlights the way the surrogate’s fit can never “be exact.”88

Marie Bryant’s on-screen performance with Grable, in contrast, establishes that not all surrogates are remembered and forgotten in the same way. In the 1950 film Wabash Avenue, Bryant shares the screen with Grable in a credited but non-dancing role, as Elsa, Grable’s character’s maid. The star and dancer/choreographer appear together in two scenes: one in Grable’s dressing room, and one backstage, just after Grable has finished a musical performance. In the latter, Bryant greets Grable’s character with a fawning “Oh, Miss Ruby” as Grable walks off stage, thrusts her bouquet of flowers at Bryant, and walks right past her. Bryant’s presence is so brief that it’s easily missed. Certainly, Grable hardly sees her. The one-sided transmission captured on screen – the hand-off of flowers from Grable to Bryant, Bryant’s unreturned gaze – is almost exactly the converse of the exchanges documented in the Ebony coverage, in which white stars solicit Bryant, eye contact is returned, and white bodies look to and learn from Bryant. There is almost a violence to the way that Bryant is remembered on-screen that intimates an urgency to forgetting that Bryant stood for a time in Grable’s place and served as her choreographer and coach on this very film. This violence suggests that, as much as surrogation may have been a necessary pre-condition of the white dancing film star’s emergence on screen, it demanded considerable policing. It also reconfirms Keeling’s insight about how fraught the issue of indexicality is even in pre-digital film: the image of blackness here completely fails to represent the off-screen relationship between Bryant and Grable, even as that on-screen portrayal serves to uphold the fiction that Grable’s image is a faithful representation of her inherent physicality.89 The white female body that circulates via the screen smoothes over and erases even as it unwittingly indexes the corporeal exchanges and substitutions that preceded and produced it.

Under this light, the white incorporation that Cherniavsky theorizes as the privileged form of embodiment is clearly exposed as a myth, a myth that the technology of the dance-in both explodes and preserves. The body of the white female dancing film star is not just at risk of dispersal; it is already dispersed, already an assemblage of others’ terpsichorean motions and teachings. The privilege of white corporeality, then, lies simultaneously in the right to reproduce others’ motions and the right to conceal those reproductions. It lies simultaneously in the right to occupy the position that others have saved for you and to dis-place those who have stood and danced in your place. It lies in the right to choose when to return your surrogate’s gaze and when to refuse to see. It lies in the right to appear autonomous and original when the flesh that your own body indexes is staring you in the face.

Biography

Anthea Kraut is Professor in the Department of Dance at UC Riverside. She is the author of Choreographing the Folk: The Dance Stagings of Zora Neale Hurston (University of Minnesota Press, 2008) and Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance (Oxford University Press, 2015), as well as essays that have appeared in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies, The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reeanctment, The Routledge Dance Studies Reader, and Worlding Dance, Theatre Journal, Dance Research Journal, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, The Scholar & Feminist Online, and Theatre Studies.

Email: anthea.kraut@ucr.edu

References

Albright, Ann Cooper. Choreographing Difference: The Body and Identity in Contemporary Dance. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1997.

Banerji, Anurima. “Dance and the Distributed Body: Odissi, Ritual Practice, and Mahari Performance.” About Performance 11 (2012): 7-39.

Basinger, Jeanine. The Star Machine. New York: Random House, 2007.

“Behind the Scenes in Hollywood.” The Gaffney Ledger, Feb. 8, 1951, 11.

Belmar, Sima. “Behind the Screens: Race, Space, and Place in Saturday Night Fever.” In The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies. Ed. Douglas Rosenberg. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. 461-79.

Bench, Harmony, “Choreographing Bodies in Dance-Media,” Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2009.

Bench, Harmony and Simon Ellis, “Editors’ Note: On Community, Collaboration, and Difference.” The International Journal of Screendance 5 (2015). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v5i0.4866

____, ed. “Editorial: Solo/Screen.” The International Journal of Screendance 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v8i0.5891

Bernardi, Daniel, ed. The Birth of Whiteness: Race and the Emergence of U.S. Cinema. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

____, ed. Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Billman, Larry. “Angie (Angela) Blue (Deshon).” In Film Choreographers and Directors: An Illustrated Biographical Encyclopedia, with a History and Filmographies, 1893 through 1995. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1997, 240-41.

____. Betty Grable: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Black, Shirley Temple. Child Star: An Autobiography. New York: Warner Books, 1988.

“Blanche Sweet Never Requires Dance Double,” Los Angeles Daily Times, June 11, 1925, 11.

Blanco Borelli, Melissa and Raquel Monroe, “Editorial: Screening the Skin: Issues of Race and Nation in Screendance.” The International Journal of Screendance 9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v9i0.6451

Bogle, Donald. Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams: The Story of Black Hollywood. New York: One World, 2005.

Brannigan, Erin. Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195367232.001.0001

Calvin, Dolores. “Marie Bryant Gets No Credit,” The California Eagle, April 20, 1950, 17.

Catton, Pia. “It’s Hard Work Being Jennifer Lawrence’s Body Double, Especially for Jennifer Lawrence,” Daily Beast, March 2, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/its-hard-work-being-jennifer-lawrences-body-double-especially-for-jennifer-lawrence. Accessed June 22, 2018.

Cherniavsky, Eva. Incorporations: Race, Nation, and the Body Politics of Capital. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Chisholm, Ann. “Missing Persons and Bodies of Evidence,” Camera Obscura 43, 15.1 (2000): 123-161.

Clover, Carol. “Dancin’ in the Rain,” Critical Inquiry 21.4 (Summer 1995): 722-747. https://doi.org/10.1086/448772

Columbia, David Patrick. “The Man Who Danced with Fred Astaire,” The Dancing Times (May and June 1991): 759, 848-850.

Crawley, Ashon. Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility. New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

“Dance Stand-in.” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 15, 1935, p. C9.

De Lauretis, Teresa. Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1987. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19737-8

Delameter, Jerome. Dance in the Hollywood Musical. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981.

Doane, Mary Ann. “Indexicality: Trace and Sign: Introduction.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18.1 (2007): 1-6.

Dodds, Sherril. Dance on Screen: Genres and Media from Hollywood to Experimental Art. London: Palgrave, 2001.

duCille, Ann. “The Shirley Temple of My Familiar,” Transition 73 (1997): 10-32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2935441

Dyer, Richard. White. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

Edwards, Anne. Shirley Temple: American Princess. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2017.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 2008.

Fantle, David and Tom Johnson. Reel to Real: 25 Years of Celebrity Interviews from Vaudeville to Movies to TV. Oregon, WI: Badger Books, Inc, 2004.

Feuer, Jane. The Hollywood Musical. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

“Film Beauty,” Pittsburgh Courier, Nov. 14, 1942.

Folkart, Burt A. “E. Meglin, 93; ‘Meglin Kiddies’ Dance Instructor,” Obituary, Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1988, http://articles.latimes.com/1988-06-25/news/mn-4707_1_meglin-kiddies. Accessed June 25, 2018.

Foster, Susan Leigh. “Dancing Bodies.” In Meaning in Motion: New Cultural Studies of Dance. Ed. Jane Desmond. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1997. 235-58.

Franceschina, John. Hermes Pan: The Man Who Danced with Fred Astaire. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199754298.001.0001

Gavin, James. Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne. New York: Atria Books, 2009.

Genné, Beth. Dance Me a Song: Astaire, Balanchine, Kelly, and the American Film Musical. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

George-Graves, Nadine. “Identity Politics and Political Will: Jeni LeGon Living in a Great Big Way.” In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Politics. Ed. Rebekah J. Kowal, Gerald Siegmund, Randy Martin. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 511-34.

Gil, José. “Paradoxical Body.” TDR: The Drama Review 50:4 (Winter 2006): 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2006.50.4.21

Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. The Black Dancing Body: A Geography from Coon to Cool. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-03900-2

____. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Grau, Andrée, “When the Landscape becomes Flesh: An Investigation into Body Boundaries with Special Reference to Tiwi Dance and Western Classical Ballet.” Body & Society 11.4 (2005): 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X05058024

Grody, Svetlana McLee and Dorothy Daniels Lister. Conversations with Choreographers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1996.

Harris, Avanelle. “I Tried To Crash the Movies,” Ebony, August 1946, 5-10.

Hatch, Kristen. Shirley Temple and the Performance of Girlhood. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015.

Hill, Constance Valis. “From Bharata Natyam to Bop: Jack Cole’s ‘Modern’ Jazz Dance.” Dance Research Journal 33.2 (Winter 2001/02): 29-39. https://doi.org/10.2307/1477802

Johnson, Erskine. “In Hollywood,” Miami Daily News-Record April 5, 1943, 4.

Jones, Grover. “Star Shadows.” Colliers Apr. 30, 1938, 18, 44-46.

Keeling, Kara. “Passing for Human: Bamboozled and Digital Humanism.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 15:1 (2005): 237-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407700508571495

Knight, Arthur. “Star Dances: African American Constructions of Stardom, 1925-1960.” In Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness. Ed. Daniel Bernardi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001. 386-414.

Kobal, John. People Will Talk. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Kraut, Anthea. Choreographing Copyright: Race, Gender, and Intellectual Property Rights in American Dance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199360369.001.0001

____. “‘Stealing Steps’ and Signature Moves: Embodied Theories of Dance as Intellectual Property.” Theatre Journal 62.2 (May 2010): 173-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/tj.0.0357

Levette, Harry. “Dorothy Dandridge Hurt So Substitute Continues Work.” Chicago Defender, Sept. 16, 1944, 6.

Lipsitz, George. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006.

Mainwaring, Dan. “Hollywood Nobodies.” Good Housekeeping (April 1938): 40-41+.

Manning, Erin. Always More Than One: Individuation’s Dance. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

Martin, Pete. “The World’s Most Popular Blonde.” Saturday Evening Post, April 15, 1950, 26-27+.

McGee, Tom. Betty Grable: The Girl with the Million Dollar Legs. New York: Welcome Rain Publishers, 1995.

“Movie Dance Director.” Ebony 5 (April 1950): 22-26.

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. New York: Vintage Books, 1970, 2007.

Mullen, Haryette. “Optic White: Blackness and the Production of Whiteness.” Diacritics 24.2/3 (Summer – Autumn 1994): 71-89. https://doi.org/10.2307/465165

“Newcomer Doubles for Dot Dandridge in ‘Pillar to Post,’” Pittsburgh Courier, Sept. 6, 1944.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge, 1986.

Perron, Wendy. “Putting the Black Swan Blackout in Context,” Dance Magazine blog, March 11, 2011, https://www.dancemagazine.com/putting-the-black-swan-blackout-in-context-2306864121.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

Petty, Miriam J. Stealing the Show: African American Performers and Audiences in 1930s Hollywood. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

Pin-Up Girl. Twentieth Century Fox. Film. 1944.

Prescod, Janette. “Marie Bryant.” In Notable Black American Women, Book II. Ed. Jessie Carney Smith. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc., 1996. 71-73.

Redmond, Sean. “The Whiteness of Stars: Looking at Kate Winslet’s Unruly Body.” In Stardom and Celebrity: A Reader. Ed. Sean Redmond and Su Holmes. London: Sage Publications, 2007. 263-274. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446269534.n25

Roach, Joseph. Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Rogin, Michael. Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Rosenberg, Douglas, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199981601.001.0001

Rosenberg, Douglas. Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199772612.001.0001

Schmeltzer, Randy. “‘Black Swan’ Blasted for Ballet Cover-Up.” Adweek, March 30, 2011, https://www.adweek.com/digital/black-swan-blasted-for-ballet-cover-up/. Accessed June 22, 2018.

Schwartz, Selby Wynn. “Light, Shadow, Screendance: Catherine Gallaso’s Bring on the Lumière!” In The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies, ed. Douglas Rosenberg. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. 205-24.

Slide, Anthony. Hollywood Unknowns: A History of Extras, Bit Players, and Stand-Ins. Jackson, MI: University of Mississippi Press, 2012.

Snead, James. “Shirley Temple.” In White Screens/Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side. New York: Routledge, 1994. 47-66.

Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17.2 (Summer, 1987): 64-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/464747

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385318

Tsai, Addie. “Hybrid Texts, Assembled Bodies: Michel Gondry’s Merging of Camera and Dancer in ‘Let Forever Be,’” The International Journal of Screendance 6 (2016). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v6i0.4892

“Twentieth Century Fox Archives.” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/3675305/20th-Century-Fox-Archives.html. Accessed November 30, 2018.

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly. Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.170676

Wabash Avenue. Twentieth Century Fox. Film. 1950.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Duke University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822376491

Westbrook, Robert B. “‘I Want a Girl, Just Like the Girl that Married Harry James’: American Women and the Problem of Political Obligation in World War II.” American Quarterly 42.4 (December 1990): 587–614. https://doi.org/10.2307/2713166

Notes

“Dance Stand-in.” I wish to express my gratitude to two anonymous reviewers, as well as to editor Harmony Bench, whose feedback and encouragement made this essay much stronger than it otherwise would have been. Any and all errors and oversights are completely my own.↩

Jerome Delameter, Dance in the Hollywood Musical.↩

Anthony Slide, Hollywood Unknowns, 3; Ann Chisholm, “Missing Persons,” 124.↩

Chisholm, 127. Both Chisholm and Slide tell us that stand-ins became commonplace in the 1930s. A 1938 article in Colliers reports that stand-ins originated with Polish silent film actress Pola Negri, who “couldn’t stand still long enough for the electricians to spot their lights or the cameramen to focus, so the director, out of sheer necessity, resorted to a dummy for all preliminary work.” Grover Jones, “Star Shadows,” 46.↩

Chisholm, 128, 125.↩

As Chisholm writes, “the pervasiveness of doubling nearly always was shrouded or contained by industry publicity releases” (128).↩

The use of dance doubles in film evidently preceded the use of dance-ins. A 1925 article in the Los Angeles Daily Times reported that white silent film star Blanche Sweet “never requires the service of a double in scenes where she is called upon to execute difficult solo dances.” “Blanche Sweet Never Requires Dance Double.”↩

See, for example, Wendy Perron, “Black Swan Blackout,” and Randy Schmeltzer, “‘Black Swan’ Blasted.” In what was no doubt an effort to avoid a similar controversy, Twentieth Century Fox was much more transparent about the dance doubling work that American Ballet Theatre’s Isabella Boylston did for Jennifer Lawrence in the 2018 film Red Sparrow. See Pia Catton, “It’s Hard Work.”↩

Slide notes that some stand-ins went on to be performers “in their own right” (119), and, as I will discuss below, some dance-ins did appear on screen as extras and chorus dancers.↩

My sincere thanks to Yumi Pak for encouraging me in a much earlier presentation of this research to dwell on this ambiguity.↩

In their “Editors’ note” to Volume 5 of this journal, Harmony Bench and Simon Ellis refer to “[s]creendance’s development as a hybrid discipline.” See also Douglas Rosenberg, Screendance, 2, 11; Selby Wynn Schwartz, “Light, Shadow, Screendance,” 205.↩

Sherril Dodds, Dance on Screen, 29, 170-71, 174.↩

Rosenberg, Screendance, 55.↩

Addie Tsai, “Hybrid Texts.”↩

White stars were not the only ones to rely on “supplementary bodies.” Despite African Americans’ too-frequent omission from academic discourse on stardom, and despite the massive barriers created by Jim Crow racism, the handful of African Americans who managed to become film stars also depended on stand-ins and doubles to help produce the gendered and racialized representations that appeared on screen. Jeni Le Gon, for example, both choreographed and served as a dance-in for Lena Horne in the number “Sping” in the 1942 film Panama Hattie. LeGon actually received a contract with MGM before Horne but was dropped because she was perceived to be a threat to the white tap dancer Eleanor Powell, also under contract with MGM. See James Gavin, Stormy Weather, 107, and Nadine George-Graves, “Identity Politics and Political Will.” In addition, an African American performer named Millie Monroe served as Horne’s stand-in for Cabin in the Sky. See “Film Beauty.” I have also found evidence that, in one shot in the 1945 film Pillow to Post, the African American actor/dancer Louise Franklin doubled for Dorothy Dandridge when Dandridge was unavailable. “Newcomer Doubles for Dot Dandridge;” Harry Levette, “Dorothy Dandridge Hurt.” A 1946 article in Ebony magazine by Avanelle Harris, an aspiring film star who had appeared in uncredited dance roles in films for years and also served as a stand-in for Horne, offers a scathing account of the obstacles African American dancers faced in Hollywood. Alternately deemed too light-skinned and too dark-skinned, losing roles to white women who were artificially darkened to play exotic Others, Harris and her colleagues made the “bitter” discovery that Lena Horne’s success did not ultimately translate to more opportunities for them. Avanelle Harris, “I Tried to Crash the Movies.” Harris’s report is a particularly poignant illustration of scholar Miriam Petty’s argument that African American performers had only the most “limited access within Hollywood’s economy of power and resources.” Petty, Stealing the Show, 5. My argument, then, is not that dance-ins were productive solely of whiteness. Rather, I’m interested in how the acts of substitution between white stars and their dance-ins can help expose the workings of white privilege. By a similar token, although male movie stars, too, relied on dance-ins, my focus here is on how dance-ins supported the production of white femininity.↩

Sima Belmar, “Behind the Screens.”↩

Rosenberg, Oxford Handbook, 1.↩

As Beth Genné writes in her recent Dance Me a Song, at its peak in the middle of the twentieth century, the Hollywood studio system possessed “vast and deep human and technical resources,” many of whom “remained buried in the opening credits or went entirely uncredited.” These included dance assistants “who performed a variety of tasks” and “acted as partners” to choreographers. Genné, 7.↩

I refer here to Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s pioneering work on the Africanist influences on American dance performance. See Digging the Africanist Presence. For examples of the Africanist influences on celebrated Hollywood choreographers like Gene Kelly, Jack Cole, and Bob Fosse, see Clover, “Dancin’ in the Rain;” Hill, “From Bharata Natyam to Bop;” and Gottschild, The Black Dancing Body, 175. I address choreographer Hermes Pan’s indebtedness to black dance sources a bit later in this essay.↩

Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye; Ann duCille, “The Shirley Temple of my Familiar;” James Snead, “Shirley Temple;” Kristen Hatch, Shirley Temple.↩

My thanks to an audience member at The Ohio State University, where I gave an earlier version of this paper, for asking how child labor laws may have driven the need for Temple’s dancing stand-in. On the degree to which child-labor laws affected Temple, see Anne Edwards, Shirley Temple. Although it was not until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act placed limitations on child labor, in her autobiography, Child Star, Shirley Temple Black writes that stand-ins “made good business sense” for the studios because California state law “limited[her] to four hours work each day, plus the three hours of school.” Black, 63.↩

Theresa De Lauretis, Technologies of Gender, 3, 2.↩

As Daniel Bernardi acknowledges, “racist practices dominate the industrial, representational, and narrational history of the medium.” Bernardi The Birth of Whiteness, 4-5. See also Bernardi, Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness, and volume 9 of The International Journal of Screendance, which is devoted to interrogating the “assumed heteronormative, white space of the screen.”↩

Richard Dyer, White, 83, 122-42.↩

Dan Mainwaring, “Hollywood Nobodies,” 137. A 1938 article in Colliers likewise observed that “many stand-ins resemble their stars so much that they can also double for them” (Jones, “Hollywood Nobodies,” 44). This has not always been the case for black actors, however. Dyer cites an example of a white woman standing in for Cicely Tyson during production of the 1976 film The Blue Bird with disastrous results. Dyer, 97. Similarly, in the fall of 2014, the Warner Bros. (WB) television show “Gotham” generated controversy when it was discovered that they had employed a white stunt woman to double for an African American guest star. Engaging in a practice known as “painting down,” apparently Hollywood’s preferred term for blackface, the stuntwoman had “dark makeup applied to the face, in a hair and makeup test, in advance of two days of filming in New York” before public outrage caused the WB to hire a black stunt woman and apologize for their “error.” As the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) contract governing stunt doubles states, “When the stunt performer doubles for a role which is identifiable as female and/or black, Hispanic, Asian Pacific or Native American, and the race and/or sex of the double is also identifiable, stunt coordinator shall endeavor to cast qualified persons of the same sex and/or race involved….” http://deadline.com/2014/10/gotham-stunt-woman-blackface-warner-bros-848969. Accessed July 8, 2015.↩

Thus far, I have not discovered Harper’s name in any other sources on Temple’s career. Biographer Edwards lists Marilyn Granas and Mary Lou Islieb as Temple’s stand-ins (77), as do Slide (127) and Black (70). It is possible that the Los Angeles Times mistakenly identified Granas as Harper. In her autobiography, Temple describes Granas as “someone I vaguely recalled from our ranks at Meglin’s.” Black, 63.↩

The clip is available here: http://www.historicfilms.com/tapes/53371. Accessed June 26, 2018. According to the Los Angeles Times, when Meglin Kiddies founder Ethel Meglin merged her dance studios with two other organizations in 1936, she “presided over what was believed the largest dance organization in the nation-137 schools.” Burt A. Folkart, “E. Meglin, 93.” Judy Garland also got her start at the Meglin Dance Studio. For more on the Meglin Studios, see Edwards, 28-30; and Black,1, 5-6.↩

On the ways African American performers have defined and “stolen” stardom on different terms from the white establishment, see Arthur Knight, “Star Dances,” and Petty.↩

Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead, 3.↩

Idem, 80, 2.↩

Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 46.↩

Gottschild, Digging the Africanist Presence.↩

Bench and Ellis. See also Tsai.↩

Erin Manning, Always More Than One, 16. In a somewhat different manner, José Gil writes that “Thanks to the space of the body, the dancer, while dancing, creates virtual doubles or multiples of his or her body.” Gil, “Paradoxical Body,” 24.↩

Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby,” 67.↩

Idem, 74, emphasis in original.↩

Idem, 67.↩

Ashon Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath, 59. See also Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus for an in-depth engagement with and expansion on Spillers’s notion of flesh.↩

Dance scholars’ use of the word “corporeality” (which I use throughout this essay) may be a way of grappling with the simultaneous materiality of flesh and discursiveness of the body, although, as I have written elsewhere, there is not exactly consensus on whether the “corporeal” refers to a material and/or a discursive realm. Anthea Kraut, Choreographing Copyright, 14. It is worth noting, too, that the space Spillers opens up between flesh and body shares some similarities with dance scholar Ann Cooper Albright’s formulation of the moment of dancing as a “double moment of representation” in which there is slippage between a dancer’s “somatic identity (the experience of one’s physicality) and a cultural one (how one’s body renders meaning in society).” Albright, Choreographing Difference, xxiii. The work of Spillers and other critical race theorists should encourage us to give more thought to how the somatic and the cultural converge and diverge differently across racial lines. Dance scholars have also challenged Western notions of a bounded body from other angles. See, for example, Andrée Grau, “When the Landscape becomes Flesh” and Anurima Banerji, “Dance and the Distributed Body.”↩

In Dyer’s influential discussion, one of the central paradoxes of whiteness is that it aspires to “something that is in but not of the body” and involves a “vividly corporeal cosmology that most values transcendence of the body.” Dyer, 14, 39.↩

Eva Cherniavsky, Incorporations, xiv.↩

Idem, xv, emphasis in original.↩

Like all racial formations, whiteness is historically contingent. While this essay’s examples are drawn from the middle of the twentieth century, I am also interested in how whiteness maintains its corporeal privilege in shifting historical conditions. On “racial formations,” see Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States.↩

My thoughts here are inspired by a talk given at UC Riverside on May 16, 2018 by Kara Keeling, titled “‘I’m a Man Eating Machine’: On Digital Media, Corporate Cannibals, and (Im)Proper Bodies,” with a response by Grace Kyungwong Hong. The talk was part of the “Undisciplined Encounters: Experimental Dialogues on Critical Ethnic Studies” series.↩

Film scholars’ concept of indexicality is indebted to the semiotic theory of Charles Sanders Peirce.↩

Keeling, “Passing for Human,” 238.↩

Idem, 244.↩

For Cherniavsky, film itself, as a mass medium that converted white stars into “commodity-images,” posed a crisis for the status of white women. She argues that the film star’s “glow” (in Dyer’s terms) served to “(re)mediate…her implication in the commodity form.” Cherniavsky, xxv.↩

Keeling cites Frantz Fanon’s famous discussion of the anxiety he experiences waiting for images of “the Black” to appear on screen, an image that is “radically incommensurate with Fanon’s own sense and understanding of” his pre-filmic reality. Keeling, “Passing for Human,” 244. See Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks.↩

Jane Feuer identifies the era spanning “the coming of sound in 1927 to the television era of the mid-1950s” as epitomizing “the golden age of Hollywood’s studio era in the popular imagination” (ix).↩

Erin Brannigan, Dancefilm, 142, 145.↩

Kraut, “Signature Steps.”↩

Jeanine Basinger, The Star Machine, 518.↩

Robert B. Westbrook, “‘I Want a Girl,’” 596; Tom McGee, Betty Grable, 85; George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, 76; Basinger, 519.↩

Westbrook, 599, 600.↩

As Pan later recalled, the first time he met Blue, “She was wearing a bikini bathing suit and a live marmoset on her shoulder. Her appearance was so outrageous I hired her just because I thought she’d be fun.” Quoted in John Franceschina, Hermes Pan, 55.↩

Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, Conversations with Choreographers, 8; David Patrick Columbia, “The Man Who Danced,” 848.↩

Grody and Lister, 8.↩

Franceschina, 106, 110; Pete Martin, “The World’s Most Popular Blonde.”↩

Franceschina, 122, 109.↩

Idem, 122.↩

John Kobal, People Will Talk, 630. Unsurprisingly, McGee’s biography of Grable contains a more favorable appraisal of Grable’s dancing. McGee writes that Pan recalled Grable as possessing a “‘natural and graceful’ dancing style” and that Pan considered Grable, along with Rita Hayworth, one of the “two top female dancers on the screen.” McGee 47, 84.↩

Martin, 106; Columbia, 848. On the surface, Grable’s own admission of averageness and her treatment like a chorus dancer might seem to compromise the legitimacy of her star status. But film scholar Sean Redmond reminds us that it is the paradoxical simultaneity of extraordinariness and ordinariness, uniqueness and commonness, that lies “at the heart of white stardom.” Redmond, 267. See also Dyer.↩

Columbia, 848.↩

Mainwaring, 137.↩

Redmond, 266. Redmond draws here on the work of theorists John Ellis and Roland Barthes.↩

According to The Telegraph and Rob Easterlea, the former director of 20th Century Fox’s photo archives, the pin-up photograph of Grable was also the product of airbrushing. Easterlea is quoted as saying, “They airbrushed out a garter she was wearing on her left leg, to make her look less slutty, and enhanced the shadows under her left butt, to make it really pop. So you’re left with healthy-as-apple-pie sexuality, which GIs went crazy for when the United States entered the war.” “Twentieth Century Fox Archives.”↩

Jones.↩

In addition to Pan, the list of choreographers with whom Grable worked includes Jack Cole, Billy Daniel, and Busby Berkeley. See McGee and Larry Billman, Betty Grable.↩

Columbia, 759.↩

See Gottschild, Digging the Africanist Presence.↩

I am indebted to John Franceschina for his extreme generosity in sharing his Pan materials with me, as well as to Micheline Laski, Pan’s niece, for granting me permission to publish Pan’s personal photos.↩

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby,” 65.↩

Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Mammy, 3. See also Harryette Mullen’s discussion of the “black woman as a conflicted site of the (re)production of whiteness.” Mullen, “Optic White,” 82.↩

Franceschina, 17. Elsewhere, Pan described Clark as “a black kid who was our houseboy and drove for us….He was a little older than I was and he used to teach me all kinds of shuffles, the Black Bottom and the Charleston. From these beginnings, I got my show business start….” Pan traced his show business career back to Clark quite literally. As he reported in an interview, on his first day working with Astaire, when asked if he had any ideas to fill out a solo tap dance, “something clicked in my mind and I remembered a break that Sam Clark had taught me back in Tennessee. I showed it to Fred and he loved it. After that he always called for me….” David Fantle and Tom Johnson, Reel to Real, 87, 89. Franceschina’s biography of Pan is full of other anecdotes that document the influence of African American aesthetics on his choreography.↩

Asymmetry is one of the Africanist aesthetic principles that Gottschild identifies in Digging the Africanist Presence.↩

Janette Prescod, “Marie Bryant.” See also Donald Bogle, Bright Boulevards, 240-43.↩

Erskine Johnson, “In Hollywood,” 4; “Movie Dance Director.”↩

See an online clip of Bryant dancing between the 0:17 and and 0:37 marks here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EFyDd8CFLVw. Accessed July 10, 2018.↩

Notably, Angie Blue also worked on both of these films as an assistant to Daniel. Billman, “Angie (Angela) Blue (Deshon),” 241; “Behind the Scenes in Hollywood,” 5. The extent to which Blue and Bryant interacted on these films is unknown. It was not uncommon for different choreographers and coaches to work with stars on different numbers on a particular film, but the difficulty of finding any documentation of Blue’s and Bryant’s relationship is a reminder of the ways the archive reflects the interests of the powerful.↩

“Movie Dance Director,” 26.↩

Ibid.↩

Susan Leigh Foster, “Dancing Bodies,” 237-38.↩

“Movie Dance Director,” 26.↩

Gottschild, The Black Dancing Body, 148.↩

Roach, 6.↩

Franceschina, 130.↩

Roach, 3.↩

Dolores Calvin, a reporter for the African American newspaper The California Eagle, took note of the vast incongruity between Bryant’s on-screen image and her off-screen role. In an article titled “Marie Bryant Gets No Credit,” she expressed grave disappointment that Billy Daniel received sole screen credit for Wabash Avenue’s choreography, despite Bryant’s “official capacity as assistant dance director, and a great necessity to the department,” while being “cast…in a menial maid’s role where the average layman, not knowing of her great talent, would chalk up her appearance as ‘just another maid.’” Calvin, “Marie Bryant Gets No Credit,” 17.↩